Pakistan's deadly descent into polio contagion

- Published

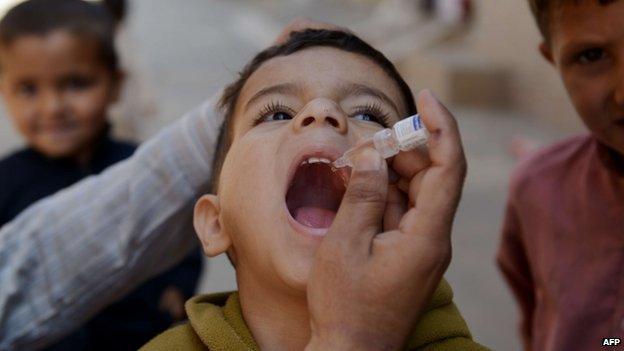

Pakistan is one of three countries where polio is endemic

Pakistan was close to eradicating polio 10 years ago. But conspiracy theories, a Taliban insurgency and drive-by shootings of polio workers have reversed the gains. The BBC's M Ilyas Khan reports from the frontline of the government's war against the virus and the militants' war against its vaccinators.

"Polio workers had been shot in the area before, but we never imagined it could happen to us."

Falak Naz, a member of the World Health Organisation's polio eradication effort in north-western Pakistan, is in a desperate situation.

"I never anticipated I would be stranded in Peshawar city with an injured wife," he tells me at the Lady Reading hospital, where he has been tending his wife, one of several family members injured in a gun and grenade attack on his home in a rural district in April.

Falak Naz has been left with no home after the attack in Charsadda

"I don't have the resources to take up a place in this city, and going back home is not only unsafe, I don't have proper living quarters there."

That attack on him was the second in a month in which gunmen have broken with the past pattern of drive-by shootings on the streets, and have instead followed health workers into their own homes.

Conspiracy theories

Pakistan is one of three countries where polio is endemic and the WHO recently issued a grave warning about the resurgent threat of the polio virus. Part of the reason is precisely the inability of Pakistan to immunise some of its children in the most vulnerable areas.

The violence is relentless and the source is ultimately the Taliban's conspiracy theories about the polio vaccine. As the death toll of the health workers rises, so does the incidence of polio.

In the four months since January, Pakistan has reported 59 new cases of polio, an all-time high for this generally low-transmission season. Of these, 42 cases have been reported from the tribal area of North Waziristan alone.

And this is where the reason for Pakistan's failure to eradicate polio lies, says Dr Imtiaz Ali Shah, head of the provincial government's Polio Monitoring Cell in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP).

"The polio virus is under control all over the country," he says. "Cases reported in the KP, and even in Karachi, are an extension of the situation in Waziristan, where non-state groups do not allow vaccination. It is a political issue, which technical people like us cannot solve."

Pakistan was close to eradicating polio virus in 2005, when only 28 new cases were reported. Dr Shah says if not for the politics, polio could be eradicated in three months.

In that year militant groups based in Swat and parts of the tribal region along the border with Afghanistan decided to oppose the polio eradication initiative.

Despite her sister's death Amena is determined to carry on as a health worker

These groups used FM radio sermons to create hostility towards polio vaccination, calling it a conspiracy by the Americans to sexually sterilise children and thereby control the population of Muslims.

During subsequent years, health workers were roughed up in communities, or even kidnapped by organised groups. Some of them turned up dead.

The defiance grew more violent after 2011 when a Pakistani doctor was accused of running a fake vaccination campaign to help the American CIA track down Osama Bin Laden.

Dr Shah says the present spike in polio cases is directly linked to the July 2012 decision by the groups controlling the Waziristan tribal region to ban vaccination there.

'My sister was shot'

December 2012 was when trained snipers drew their first blood by staging a drive-by shooting of health workers conducting immunisation campaigns.

One of the first workers to fall to the assassins' bullets in Peshawar was a 16-year-old schoolgirl, Farzana Rahman.

Her sister and co-worker, Amena Rahman, 20, still remembers that day.

"We had been doing volunteer work for WHO for a couple of years to earn pocket money, and also because both of us aspired to become health professionals.

"So as usual, we were operating as a two-member team; Farzana would administer polio drops to children, and I would scrawl the markings on the doors of the houses we covered for future reference."

Farzana's death marked the beginning of a renewed campaign against polio workers

Farzana had just finished administering polio drops to two children at one house, and Amena was chalking on the door when she heard the shot.

"It was a dry sound, like the whack of a small cracker, or if you slap someone," she recalls.

"When I turned around, I was shocked to see Farzana sitting on the ground, leaning against the door. A man rushed away from us, jumped on a motorbike behind another man and rode away. A lady who had brought out the children for vaccination pushed the door hard to shut it from inside, and one of Farzana's fingers was caught in it. But she didn't wince."

This angered Amena. She first shouted at the lady, and then taunted her sister for being frightened by the sound of a mere cracker.

"She didn't respond, so I kneeled down before her and touched her shoulder. She fell into my lap. There was a gaping wound on the side of her head, and the blood was gushing out of it."

Shaista's polio

And so polio continues to infect the young. The illness contracted by 19-month-old Shaista Gul has come at a particularly bad time for her family.

Shaista's parents can barely afford to get by, let alone seek medical help

Her father, Wahid Gul, is just 24, but already wears the look of a withered man.

A brick-kiln worker who can earn up to just about two dollars a day at the best of times, he has been unemployed for the last six months. And since he cannot afford to own or rent a house, he lives with his equally poor in-laws.

One night in late March, the family discovered that little Shaista, a vivacious child who had learned to walk and often played with her cousins on a flat grassy ground outside the house, was running a high fever.

"In the morning, her mother tried to stand her on her feet, but she collapsed. She hasn't walked since then," he says tearfully.

"She learned to walk too soon, and she was so nimble-footed. Perhaps she caught an evil eye."

The family faces uncertain times. They have no money to pay for laboratory tests and rehabilitation exercises, and no help has arrived from the government's charity funds.

At least 33 field health workers have been killed in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province since Farzana, says Dr Shah.

"But there is little evidence of turnover among our teams, which is a sign of their resilience and courage."

Her sister Amena is a case in point. Despite having suffered the trauma of watching the murder of her sister, she plans to rejoin the campaign.

"I like this work. If I can save a life, it will make God happy. My parents agree with me."

- Published5 May 2014

- Published19 December 2013

- Published18 December 2012

- Published25 September 2015