New voting power of Chinese Indonesians

- Published

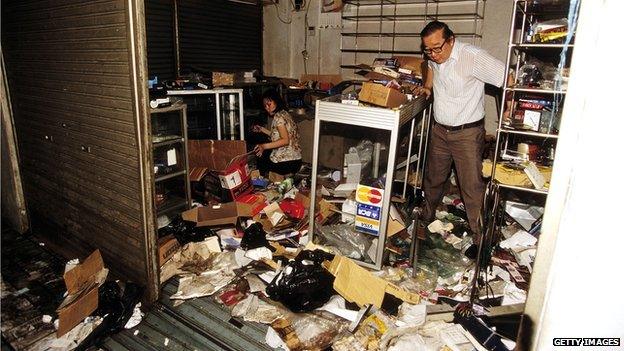

The 1998 riots in Jakarta targeted members of Indonesia's ethnic Chinese community

May 1998 was a dangerous and volatile time in Indonesia. Bloody riots left Jakarta, the Indonesian capital, in fear.

Four student protestors were shot dead by the Indonesian army while thousands of demonstrators against then President Suharto's regime clashed with security forces, which led to mayhem on the streets.

The mob targeted districts where Indonesia's ethnic Chinese minorities lived, looting shops and burning buildings. The Chinese community had historically been seen as more economically successful, educated and better connected to the political classes.

Anti-Chinese sentiment that had built up for decades peaked during this period as Indonesians took out their anger at the establishment on the Chinese minority. More than 1,000 people reportedly died and it was believed scores of ethnically Chinese women and girls were raped.

My most vivid memory of those days is of fear. As a Chinese Indonesian, I always knew that my family and I were minorities in Indonesia. I was 11 years old at the time, watching the disturbing images and hearing the gunshots on television.

My mother took me to my grandmother's house to stay for a few nights as the riots were getting closer to home. We escaped unscathed - but the trauma of those days was so severe that no one in my family can bear to discuss it. "The Chinese don't talk about their feelings," we were told by our elders.

In this file image, a Chinese man surveys the damage after a shop was looted in Jakarta on 16 May, 1998

Sixteen years have now passed, but the haunting memories of the May tragedy are still fresh for 47-year-old Mr Lim (not his real name).

Mr Lim's electronic shop and around 700 others were looted and burned in a predominantly ethnic Chinese business district in western Jakarta. "It was hard," he said. "In 1963 my mother's house was also burned because of anti-Chinese sentiment in West Java and in 1998, I experienced it myself. It was very hard."

But this year's election has brought new hope for him and many ethnic Chinese who suffered from the anarchy.

"The tragedy was a turning point for me to realise that we should know more about politics," he said.

Turning points for Indonesia's ethnic Chinese community

1999-2001: Former President Abdurrahman Wahid revoked a law forbidding Chinese cultural performances and the use of Chinese names

2004: Former President Megawati Sukarnoputri declared Chinese New Year a public holiday

2004: Marie Elka Pangestu became the first female Chinese Indonesian minister

2014: President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono issued a regulation changing the word meaning "of Chinese descent" in Indonesian ("Cina") to "Tionghoa" and China - as a country - to "Tiongkok". The word "Cina" has negative connotations for most Indonesians and it is often associated with racist slurs

'Prove them wrong'

The fate of Chinese Indonesians has changed dramatically since the days of former President Suharto's regime.

This is partly as a result of the outrage and shock that many Indonesians felt after witnessing the 1998 violence and also as a result of the fact that as Indonesia has democratised, wealth has become more evenly spread.

Today they are allowed to display their cultural identity in public, use their Chinese names and run for political office. Some have even made it to ministerial and gubernatorial posts.

Chinese customs and practices are flourishing in Indonesia today

Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, a Chinese Indonesian, is well-known in the Indonesian capital

One of the most famous Chinese Indonesian politicians is Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, Jakarta's acting governor, who has become a media sensation for his firmness and controversial statements.

But he is not the only one to have made a mark in politics. Chinese Indonesian politician Yandi Chow, 34, will make his debut as a public legislator in West Kalimantan this year. He won his seat in April's parliamentary elections.

Mr Chow started his career 10 years ago - a time when politics was still considered an unusual and risky career choice for Chinese Indonesians.

His family was extremely averse to the idea, but he says he is glad he proved them and others who doubted him wrong.

"I am living proof that the attitudes of others in the community towards us (Chinese Indonesians) were wrong. If we are given opportunities in politics, we can prove we are qualified."

How significant are Indonesia's Chinese voters?

According to the latest population census in 2010, there are 2.8 million ethnic Chinese living in Indonesia, accounting for 1.2% of the total population

Observers say this number is much higher because many Indonesians are still reluctant to admit they are of Chinese descent, fearing discrimination

Former activist and prominent businessman Sofyan Wanandi says that Indonesia's ethnic Chinese community could be as big as 10 million

'Very tight'

With the presidential elections looming the two candidates, Prabowo Subianto and Jakarta's governor Joko Widodo, are doing all they can to win over the minority vote.

Mr Subianto has gained some support from the Chinese Indonesian community - although his reputation has been smeared by allegations that he was responsible for the anti-Chinese riots that took place during the violence in 1998. Mr Subianto has consistently denied those allegations and has maintained his innocence.

Chinese voters are hoping that the new government will continue to improve minority rights

Mr Widodo - also known popularly as Jokowi - has promised to thoroughly investigate May 1998's tragedy and fight for the rights of minorities.

Whoever wins the election, Chinese Indonesians say they hope the new government will bring peace and justice in the future - and that there won't be a return to the past.

Benny Setiono, the co-founder of the Chinese Indonesian organisation INTI, says many in the community fear that security will become an issue once the votes are cast.

"The battle between the two candidates is very tight," he told me. "We are afraid that if the winner is announced and the other won't accept the results, chaos will happen."

"We hope the authorities can prevent it, because in general, whenever there's political chaos, our community always becomes the victims. It's evident throughout Indonesia's history. We have always been targeted."