Love, honour and the Pakistani girl who lived

- Published

Saba (centre) says she was shot, dumped in a canal and left for dead

When I tell Saba that I have met the man who nearly killed her, she leans forward, eager to hear what he said.

It has been a month since she was attacked in Pakistan's Punjab province.

I say that he told me that he had not intended to kill her, just teach her a lesson so that no girl from the family would dare to consider eloping again.

She leans back and says dismissively: "He's lying." She is 18 years old and slight, with fierce eyes, one of which is still bloodshot from her injuries.

The man who allegedly colluded with four others to end her life is her father - Maqsood Ahmed.

When I met him behind bars in Gujranwala central jail, where I wasn't allowed to take any recording equipment, he was unrepentant.

I asked him whether there was more shame in being in jail for attempting to murder his own daughter than in her act of elopement.

He denies attempting to murder her saying he just wanted to teach her a lesson: "[Being in jail], it's a life of honour. I haven't committed a crime. I haven't robbed anyone. If I had wanted to kill her, I would have done it at home."

'Dumped in canal'

Saba's left hand is still bandaged where a bullet shot through it; her face marked with a long scar across her cheek where another bullet grazed it.

Saba says she begged her father and others not to hurt her

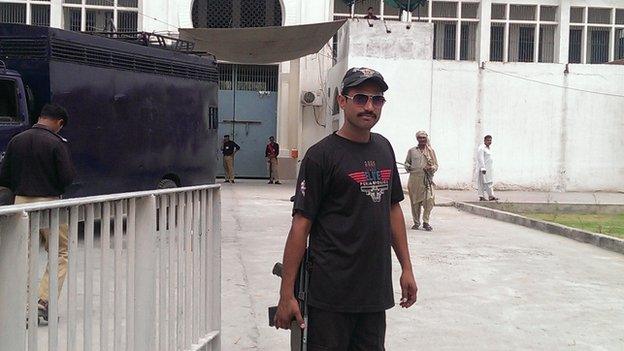

Saba's father and uncle are being kept in Gujranwala prison. Pictured here, a guard outside the prison.

She says the day after she married her fiance Qaiser, her father and uncle took her from her in-laws' home - after swearing on the Koran that no harm would come to her - shot at her and dumped her body in a canal in a sack.

She says she married her neighbour - to whom she had been engaged for a couple of years - secretly at his house because her family had been pressuring her to get married to someone else.

The day after the ceremony, her family came to collect her and took her back to her parent's home.

"It was a dark and moonless night. We were in a Toyota pick-up with a lot of people, my father, uncle, his wife and three of my uncle's friends. They had said they wanted to get some wheat. But then we reached the jungle where there are several canals. I became suspicious."

Saba tells me that she was ordered to get out of the car and she begged them not to hurt her.

"Is what I've done so bad? Why can't you forgive me?" she asked.

But they dragged her out anyway, slapping her and then firing at her twice, she reports. The second time, she fainted. When she came round, she found herself in a sack in a canal.

"The waves in the canal carried me close to the shore. I grabbed a hold of some weeds and pulled myself out. I kept walking until I reached a petrol pump, and a man there called the emergency services."

'Flawed law'

At hospital Saba recorded a statement against her father with the police.

Saba says her father and relatives lured her into this pick-up before attacking her

Her father says that he found out that Saba was in the hospital in the morning, but insists that he had left her by the canal as a warning.

"I hit her with a metal object and left her there to punish her," he admits. "Our neighbours had come to our house and raised a fuss that she had run away. It was a great shame for my family. I couldn't help myself, my emotions got the better of me."

The doctor's report clearly says that Saba's injuries resulted from bullet wounds, not a blunt instrument.

Now, Maqsood and Saba's uncle are on trial for attempted murder and kidnap - based on her testimony.

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan says there were 869 reported honour-killings last year.

According to the UN, one in five such cases worldwide happen in Pakistan. But figures of convictions are harder to come by.

"Honour crimes are filed in the lower courts and anti-terror courts, as murders or attempted murders," says human rights lawyer Hina Jillani, who has tried several such cases.

But provisions in Pakistani allow for perpetrators to be set free if the victim or heirs of the victim agree to reconcile.

"Unfortunately, the law in the country is very flawed and weighed in favour of impunity for honour-killings. In most cases, it will end in a compromise.

"First, the family will conspire to kill the woman and then conspire to forgive the person who pulled the trigger," Hina Jillani adds.

Compromise?

Saba, too, is being put under pressure from her in-laws and elders in the community to settle the matter out of court.

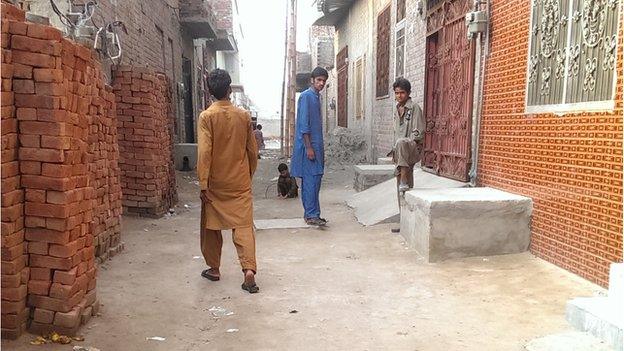

The in-laws are keeping a watchful eye over Saba...

... her love marriage means she is confined to her new family's home

She shrugs: "I don't want to forgive them. I don't want to meet my father or uncle again." Her mother and eight siblings live close by but she has no desire to meet them either.

Her mother-in-law is sitting opposite us on a cot in the courtyard, a burly woman cleaning rice for the evening meal.

She says Saba has no choice but to settle because life in a community means compromise.

"If today we refuse to reconcile, what will happen tomorrow when my other children are in trouble?"

But she also understands Maqsood Ahmed's fury.

"When somebody impugns your family's honour, it hurts. Saba is now our honour, and I'm a very strong woman, I won't even let her step out of the house."

Saba made her choice, but there is a glimmer of sadness in her eyes. She fought hard to be with the man she loves but her life is likely to be a restricted one.

- Published16 July 2014

- Published27 May 2014

- Published29 May 2014

- Published7 January 2014

- Published27 June 2013