Top Khmer Rouge leaders guilty of crimes against humanity

- Published

- comments

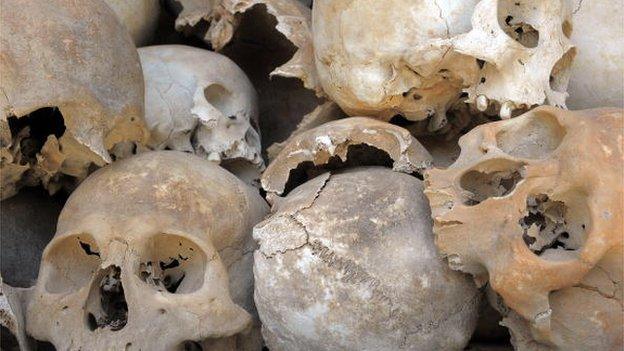

Up to two million people are believed to have died under the Khmer Rouge regime

Two top Khmer Rouge leaders have been jailed for life after being convicted by Cambodia's UN-backed tribunal of crimes against humanity.

Nuon Chea, 88, served as leader Pol Pot's deputy and Khieu Samphan, 83, was the Maoist regime's head of state.

They are the first top-level leaders to be held accountable for its crimes.

Up to two million people are thought to have died under the 1975-79 Khmer Rouge regime - of starvation and overwork or executed as enemies of the state.

Judge Nil Nonn said the men were guilty of "extermination encompassing murder, political persecution, and other inhumane acts comprising forced transfer, enforced disappearances and attacks against human dignity''.

Lawyers for the pair said they would appeal against the ruling. "It is unjust for my client. He did not know or commit many of these crimes," Son Arun, a lawyer for Nuon Chea, told journalists.

They will remain in detention while this takes place.

There was a round of applause as the verdict was reached, as Jonathan Head reports from Phnom Penh

'Anger remains'

The regime sought to create an agrarian society: cities were emptied and their residents forced to work on rural co-operatives. Many were worked to death while others starved as the economy imploded.

During four violent years, the Khmer Rouge also killed all those it perceived as enemies - intellectuals, minorities, former officials - and their families.

Khmer Rouge rule brought four years of starvation, torture and fear to Cambodians

It is believed that up to two million Cambodians died under Pol Pot's regime

Soum Rithy, who lost his father and three siblings, reacts to the verdict in Phnom Penh

Nuon Chea was seen as an ideological driving force within the regime. Khieu Samphan was its public face.

Prosecutors argued that they formulated policy and were complicit in its brutal execution.

Over three years the court has heard from some of those who lost entire families to the regime.

"My anger remains in my heart,'' Suon Mom, 75, whose husband and four children starved to death, told the Associated Press news agency.

"I still remember the day I left Phnom Penh, walking along the road without having any food or water to drink."

Jonathan Head, BBC News, Phnom Penh

After three years of hearings, and a summary of charges that ran for 90 minutes, the presiding judge delivered sentencing against the two elderly defendants surprisingly briskly. Both men were guilty of crimes against humanity, both were sentenced to life in prison.

Khieu Samphan, the urbane, international face of the Khmer Rouge, was found not to have had authority over those carrying out the worst atrocities documented by the tribunal. Nuon Chea was found guilty on all charges. Both in the end received the same sentence, somewhat academic given that both men are in their eighties, and in poor health.

They had insisted on their innocence, dismissing the accusations against them as propaganda and lies. Their defence, though, was dismissed by the tribunal as lacking credibility. Nuon Chea, unable to stand for the sentence, showed little emotion, but Khieu Samphan appeared visibly angry. They had told their families not to come and hear the verdicts.

It was in many ways an anticlimactic end to the only official accounting for the horrors of the Khmer Rouge years. The true value of this unique "hybrid" tribunal, blending international and Cambodian judicial authority, is still difficult to assess.

Outside the court, Khmer Rouge survivor Nou Saota said: "I feel so happy and relieved. A huge burden has been lifted off me."

Youk Chang, another survivor, told the BBC the verdict was "a little too late for many" but said it was vital the trial took place.

"It's important for the young population to learn this lesson so that we can prevent such atrocity from occurring anywhere, not just in Cambodia," he said.

Rights group Amnesty International, meanwhile, called the ruling "an important step towards justice", as it noted "troubling" obstacles the court had faced.

Some have criticised the slow pace and cost of the court. In 2012, a Swiss judge resigned, saying his investigations into other Khmer Rouge suspects were being blocked.

'Socialist revolution'

Both Khmer Rouge leaders denied the charges against them. In closing statements last year, they expressed remorse but said they had neither ordered deaths nor been aware of them.

In a statement shortly after the ruling, the court said both men had participated in "a joint criminal enterprise to achieve the common purpose of implementing a rapid socialist revolution... by whatever means necessary".

The pair also face a separate genocide trial. The case against them was split to accelerate proceedings, because of their age.

Who were the Khmer Rouge?

Maoist regime that ruled Cambodia from 1975-1979; Led by Saloth Sar, better known as Pol Pot

Abolished religion, schools and currency in effort to create agrarian utopia

Up to two million people thought to have died of starvation, overwork or by execution

Defeated in Vietnamese invasion in 1979; Pol Pot fled and remained free until 1997 - he died a year later

Two other former Khmer Rouge ministers were to be tried with them.

Ieng Sary, the former foreign minister, died in March 2013. His wife Ieng Thirith, who served as the regime's social affairs minister, has been ruled unfit to stand trial.

Before this, former prison chief Duch was the only senior Khmer Rouge figure held to account, but he was not part of the regime's central leadership.

He was jailed in 2010 for running the Tuol Sleng prison, where thousands of people defined as enemies of the regime were tortured and killed.

- Published16 November 2018

- Published7 August 2014

- Published14 March 2013

- Published16 September 2012