Viewpoint: Why Pakistanis crave stability

- Published

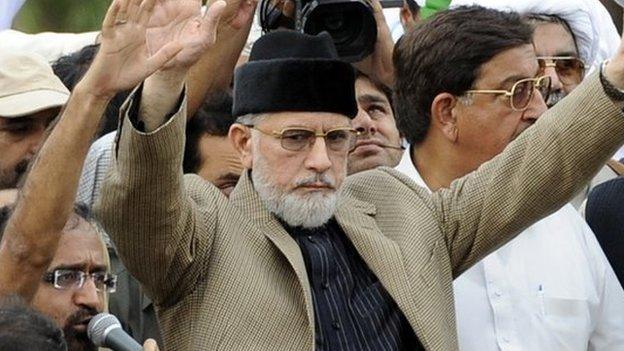

Imran Khan says last year's vote was rigged and the prime minister must quit

Pakistan needs and deserves better leaders - but it also needs stability and an end to games played by politicians and generals, argues guest columnist Ahmed Rashid.

When Imran Khan launched his movement three weeks ago to force the resignation of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and bring fresh elections, the former cricket captain-turned-politician thought the nation would mobilise in his favour.

The masses were to pour into Islamabad and just by sheer weight of numbers, they would terrify the government and force it to quit. After all, Mr Sharif's first year in power has so far looked extremely lacklustre. Every problem he was faced with a year ago has become worse.

However, what actually happened was just the opposite. The nation mobilised against Imran Khan and his supporters, and their claims that last year's election was rigged. Almost the entire political spectrum supported Mr Sharif's staying on - even his political enemies in parliament.

The business community, traders, civil society, the media, lawyers and the courts all voiced strong support for the government, the constitution and the status quo. Many of them described Imran Khan's demands as illegal and unconstitutional - but that was not the point.

The reality was that nobody wanted to see another crisis, more turmoil, another change of government, which could bring the army directly into play.

Such a reaction was not predicted. Imran Khan was advised that Nawaz Sharif's administration would fall like a pack of cards, he would flee the country and Pakistanis would welcome his departure.

Instead the country has taken a firm stand - not necessarily in favour of Mr Sharif, but in favour of stability. That is where Imran Khan and his advisers - many of them ministers for former military regimes and spy chiefs - had got it all wrong.

After decades of military coups, political turmoil, the assassination of Benazir Bhutto, the rise of Islamic extremism, a collapsing economy and the experience of the 1990s when governments were elected and fell like ninepins - people were dying for an end to all the upheavals.

Last year, they got it when for the first time a sitting elected government of the Pakistan People's Party (also deemed corrupt and incompetent) completed its term without military intervention, elections were held and a new government was chosen in a vote that was not free and fair by Westminster standards, but was deemed good enough by most people for the first transition to a democratic handover.

Mr Sharif won the election but has little to show for his first year

Of course, Nawaz Sharif in his arrogance badly miscalculated that he need not agree to Imran Khan's much earlier demands that four constituencies be looked at. If he had done that last year, the prime minister and the country may have been saved from all this turmoil.

Also, the issue is not about Imran Khan's ego (he likes to be addressed as "captain" or even "prime minister"). The crisis is also not about personalities and their clashes.

Nor is it about family ties, despite Mr Sharif's questionable performance - refusing to put in place a full cabinet, or farm out greater responsibility to the party and parliament or to act more democratically. Instead, it is his direct family that holds most of the key posts and are the key advisers, including the most inexperienced members of the family. Even his party is now fed up with his pandering to relatives.

Moreover, people are also tired of the alleged interference in political matters by Pakistan's powerful military and its feared Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) wing.

So, none of the obvious solutions in Pakistan - a military coup, the ousting of Mr Sharif, fresh elections - is favoured by the vast majority of the country's people. Instead, they want stability and better security, so they can get on with their lives.

If people want two things from the government it is better governance and an improved economy. Not much to ask for, but Imran Khan has promised neither. He has only promised to become the next prime minister. In fact, his underlying promise is greater turmoil and perhaps more bad advice from his many advisers.

Equally, the message for stability must go out squarely to the army. People are now tired of the games played by a military which has backed proxy Islamic groups to undermine Kashmir, Afghanistan and Central Asia - only to find that the same groups come home to threaten ordinary people.

Today, the Pakistani Taliban and their proxies and the groups that inhabit Lahore and other Punjabi cities are just as toxic as Islamic State (IS) in Syria and Iraq. People in Pakistan want stability, not Islamic extremism. They want learning to give them opportunities and jobs - not salvation in the next world.

Maybe the saga of the past month will make people disappointed in democracy, but surely not in the need for stability.

- Published20 August 2014

- Published16 August 2014

- Published13 August 2014

- Published18 August 2014

- Published16 August 2014