What is Malaysia's sedition law?

- Published

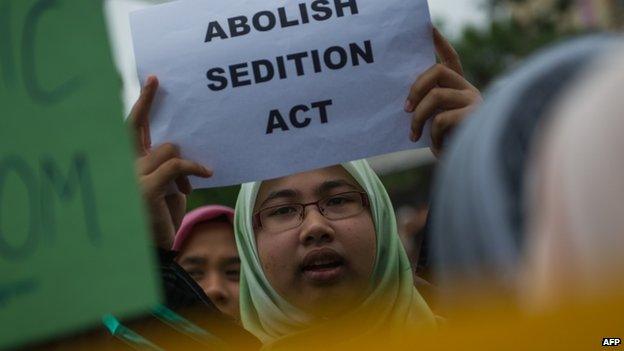

Malaysia leaders said the Sedition Act would be repealed - but it remains in place and is being enforced

Malaysia's Prime Minister Najib Razak has said he will bolster the Sedition Act, despite previously pledging to abolish the controversial law.

The act has been widely criticised for being used to silence government critics.

What does the law involve?

The Sedition Act was introduced by the British colonial government in 1948 to use against local communist insurgents. Human rights groups accused the governing Barisan Nasional coalition of expanding the scope of the law since it gained independence from the British five decades ago. They say the definition is now too vague.

Today, the law bans any act, speech or publication that brings contempt against the government or Malaysia's nine royal sultans. It also prohibits people from inciting hatred between different races and religions, or questioning the special position of the ethnic Malay majority and the natives of Sabah and Sarawak.

Those found guilty of sedition could face fines and jail terms of up to three years.

Amnesty International says, external the law is an "outdated and repressive piece of legislation" that has been primarily used against opposition politicians but in recent months have included journalists, students and academics.

PM Najib Razak may be under pressure from his own coalition not to repeal the law, analysts say

Wasn't it going to be abolished?

Yes, prior to the last general election, Prime Minister Najib Razak announced that he would repeal the Sedition Act in July 2012 because it "represents a bygone era" and was part of his reforms to develop Malaysia into a progressive democracy.

Mr Najib said the sedition law would be replaced with a National Harmony Act.

Over the last year a string of sedition charges sparked fears that the prime minister would backtrack on his promise.

Since his coalition won a slimmer majority in the last vote, some analysts and members within Mr Najib's Malay-Muslim based party told the BBC that the prime minister was facing mounting opposition to his reforms from hardliners within his coalition, who are pushing for more favourable policies over other races and religion.

Opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim is the most high-profile figure to be targeted

So who is being targeted?

Human Rights Watch estimates that at least 14 people have been charged with sedition since 2013.

Most of them are opposition politicians, activists, journalists as well as the lawyer of opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim.

Mr Anwar himself is being investigated for sedition.

In September, a professor with the prestigious University of Malaya was charged with sedition for comments related to a political event five years ago. Azmi Sharom has pleaded not guilty.

His arrest sparked a rare protest from students, academics and members of the Malaysian Bar Council.

What does government say?

In September, a Malaysian government spokesperson denied to the BBC that Mr Najib was backtracking on his promise to repeal the Sedition Act and said it will take time to find a piece of legislation that balances the right to free speech and protecting Malaysia's diverse population from racial or religious hatred.

Now, two months later, Mr Najib has announced at his annual party convention that the law will be retained without explaining why he changed his mind.

Mr Najib said he would also add more clauses to the act, which will protect the sanctity of Islam, prevent insults to other religions, and take action against anyone who calls for the cessation of the Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak.

The law has sparked some protests, which could expand if more figures are targeted

How have people reacted to this?

Opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim said this was a "regressive" move and it will plunge the country back into the "days of the Internal Security Act" - a reference to the abolished law that allowed for indefinite detention without trial and made many people self censor.

Amnesty International said the sedition investigation against Mr Anwar case is "clearly political and smacks of persecution" and have called on Prime Minister Najib to repeal the "draconian law".

Shortly after Mr Najib's announcement, Phil Robertson with Human Rights Watch tweeted that this meant the death of human rights and freedom of expression in Malaysia.

"Opposition politicians and activists watch out," he wrote.

- Published27 November 2014

- Published6 May 2014

- Published2 July 2013

- Published28 July 2020

- Published24 November 2022

- Published10 May 2018