Narendra Modi lawsuit revisits Gujarat riots on US visit

- Published

- comments

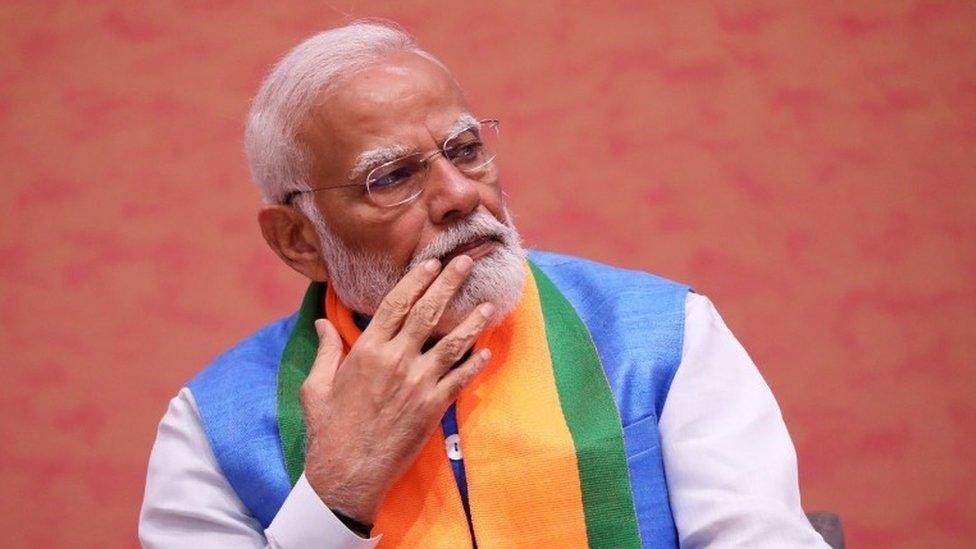

Narendra Modi is making a string of high-profile appearances while in the US

The lawsuit charging India's Hindu nationalist Prime Minister Narendra Modi with crimes against humanity during the 2002 Gujarat riots, external was timed to cause maximum embarrassment during his five-day American charm offensive.

With US officials making clear Mr Modi has immunity as a head of government while on American soil, it's likely to be little more than an irritant in the short term.

If he needs any advice he could do worse than call his chief political opponent, Sonia Gandhi.

The Congress party leader was targeted, external by the same American lawyer, under the same American statute, charged in relation to an anti-Sikh massacre in Delhi in 1984 - until that case was dismissed earlier this year.

An attempt, external by a British restaurant worker to arrest former Prime Minister Tony Blair for invading Iraq did little more than disrupt his meal.

Yet even if they are not an immediate legal threat, these opportunistic bids for justice have kept Mr Blair and other controversial world figures on their toes.

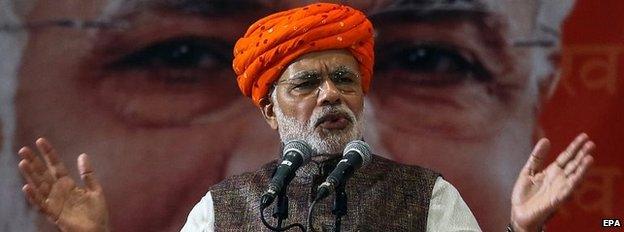

For Mr Modi, it's a reminder that questions over his actions as chief minister of Gujarat during the 2002 riots haven't gone away - despite his decisive election as prime minister in May.

While taking care not to overshadow his visit, the Indian media have still given the lawsuit respectful coverage.

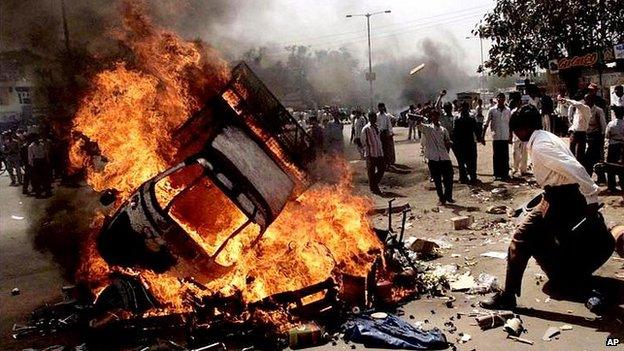

Mr Modi is accused of turning a blind eye when Hindu mobs went on a rampage of revenge in Gujarat in 2002.

The riots came after a train carrying Hindu pilgrims was torched, killing 59 people.

More than 1,000 people eventually died in the violence - most of them Muslims.

Images of the 2002 Gujarat riots flashed around the world

It was for that reason the Bush Administration denied him a visa in 2005, external, under laws barring any government official responsible for "particularly severe violations of religions freedom".

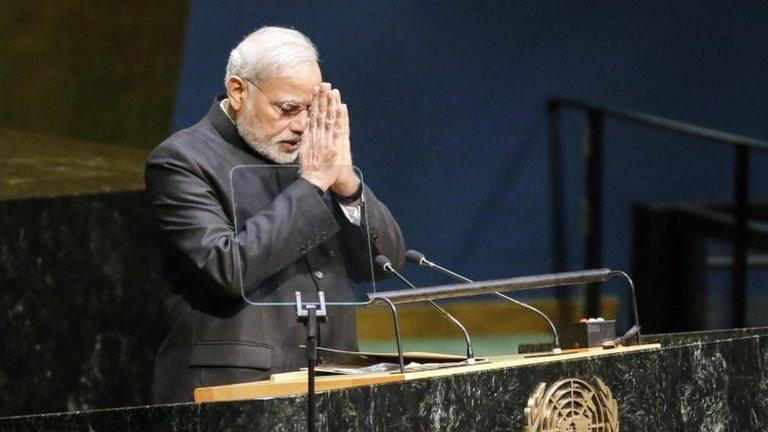

Both the Obama administration and Mr Modi want to leave that controversy behind, but technically the ban still stands and he can travel to the US only because as his nation's leader he gets an automatic visa.

Mr Modi's supporters dismiss what they call a "fake campaign" against him, pointing out that Indian courts have ruled, external there is insufficient evidence to prosecute him.

But significant doubts remain, external over the investigations that led to that verdict. And a former Gujarat cabinet minister appointed by Mr Modi was convicted, external of instigating the worst single massacre during the riots.

The prime minister's Hindu nationalist background and past anti-Muslim rhetoric, together with his apparent refusal to show remorse for the bloodshed in 2002, fuel suspicions that the full truth has yet to emerge.

Critics say Mr Modi has also been conspicuously silent over a spate of anti-Muslim incidents, external in India since becoming prime minister.

His declaration in a recent CNN interview that Indian Muslims "would live for India and die for India" was seen by some as a veiled response to such criticism.

But though some welcomed his remarks, many Muslims asked why they needed "a certificate of loyalty" from Mr Modi.

And one of the few Muslim MPs in Mr Modi's ruling NDA coalition has now spoken out, external against what he calls "the unfettered hate being spewed" against India's Muslim minority.

When he was sworn in as prime minister in May, Mr Modi promised to build an India that was "inclusive".

But at a time when the US is trying yet again to repair ties with the Muslim world in its battle with Islamic State militants, Mr Modi may prove a controversial ally.

Narendra Modi is seen as charismatic and controversial

- Published27 September 2014

- Published25 September 2014

- Published23 April 2024