Narendra Modi: India's prime minister eyeing a historic third term

- Published

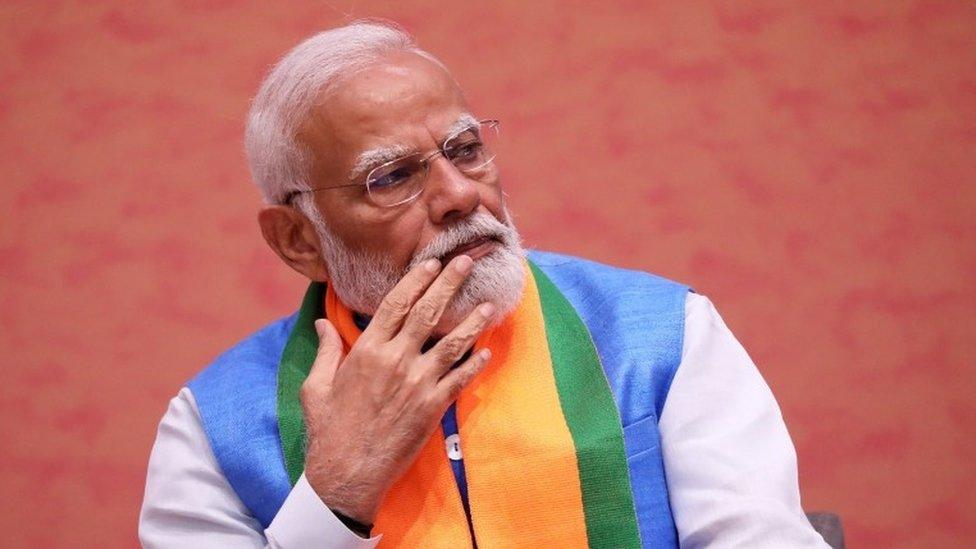

Mr Modi, seen here at the launch of his party manifesto in April 2024, is eyeing a historic third term in a row

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is eyeing a historic third consecutive term in general elections being held in April and May.

A nationwide poll by India Today magazine last August, external showed the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader's popularity remained intact after a decade in power: more than half of respondents felt he should continue to lead India.

If that happens Mr Modi, 73, will equal the three-term record of Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister.

Under Mr Modi, the BJP has become the first party to win clear majorities since Congress in the 1984 elections. He's possibly the only leader to claim mass appeal almost throughout India since Indira Gandhi, who was murdered in 1984.

Mr Modi is a divisive figure, evoking both admiration and criticism. He has promoted his brand of muscular Hindu nationalism at home and been received as India's leader on the international stage.

The BJP's electoral triumphs are often linked to Mr Modi's charisma, adept use of religious polarisation and assertive Hindu nationalism, coupled with a record of effective governance. Factors like caste, identity and a slew of welfare programmes have also contributed to his support.

In January Mr Modi opened the grand temple in Ayodhya, informally launching his campaign for a third term

In January Mr Modi opened the $220m grand temple to Hindu god Ram in Ayodhya, informally launching his campaign for a third term.

The timing of the opening leaned more towards political strategy than religious significance, building a Hindu nationalist momentum ahead of the polls. In a nationwide poll, external in February, 42% of the respondents said the opening of the temple was the major highlight of Mr Modi's government.

Mr Modi talks about India in the middle of an amrit kaal, or a golden age.

India is one of the world's fastest-growing major economies today, projected to maintain this pace in the coming years. The outlook is sustained by robust government spending, according to a Reuters poll of economists, external.

Mr Modi's government spending has primarily focused on building infrastructure. But the slow pace of private investment, education, a jobs shortage and pollution pose major challenges.

Mr Modi also envisages India as a vishwaguru or "teacher to the world", a vision he championed during India's presidency last year of the G20, whose members account for 85% of the world's GDP.

He also positioned India as the "voice of the Global South". Many believe that India's G20 presidency was a win for Mr Modi, showcasing India's achievements to a global audience and resonating with his domestic voters.

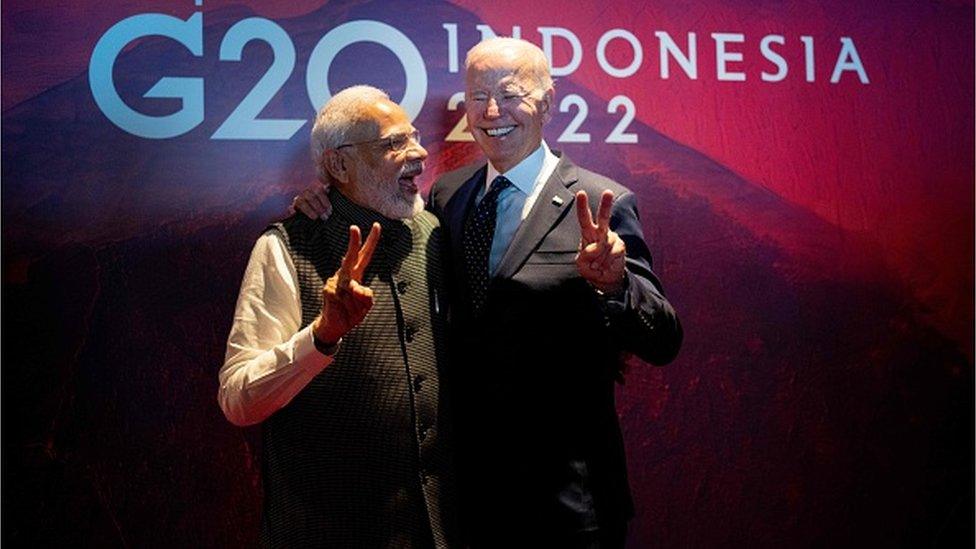

Mr Modi has bolstered ties with the US - President Biden says the partnership is 'among the most consequential' globally

In April last year, when India joined the exclusive group of countries landing on the Moon alongside America, China, and the Soviet Union, Mr Modi hailed it as the "victory cry of a new India". The lunar landing, framed as an accomplishment under the premier's leadership, seamlessly aligned with his nationalist messaging.

Mr Modi's foreign policy record has been mixed. He bolstered ties with the US, and after a grand state visit to Washington in June last year, President Joe Biden deemed the partnership "among the most consequential in the world."

A key reason is that Washington is keen to draw India closer so that it can act as a counterbalance to China's growing influence in the Indo-Pacific. But India's relations with China remain strained.

Mr Modi's critics believe his government has emboldened Hindu hotheads, curtailed space for dissent, and led to harassment and attacks on minorities, particularly Muslims, as well as activists, the press, and opposition politicians. In 2021, Sweden-based V-Dem Institute controversially said India had become an "electoral autocracy".

Mr Modi has made general elections in India largely presidential, and braved anti-incumbency.

In 2019, he secured a massive victory despite surging unemployment, declining agricultural incomes, and a slowdown in industrial production.

People wave the national flag as Mr Modi congratulates scientists for the successful Moon mission

The impact of the 2016 currency ban (also called demonetisation), aimed at uncovering undeclared wealth, and criticisms of a poorly-designed and complex uniform sales tax added to the challenges faced by many Indians. India's failure to promptly address the devastating second wave of Covid in 2021 also did not diminish Mr Modi's popularity.

Many Indians view Mr Modi as a messiah capable of resolving all their issues. According to a 2019 survey by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), a Delhi-based think tank, one-third of BJP voters indicated they would have backed a different party if Mr Modi weren't the prime ministerial candidate.

Mr Modi was propelled to power after his party's first spectacular general election win, in May 2014.

For years he had been persona non grata in the US, UK and other countries because of deadly anti-Muslim riots in Gujarat state that took place on his watch as chief minister in 2002. Mr Modi has always denied allegations that he could have done more to stop the bloodshed.

With his track record of economic success in Gujarat, Mr Modi fought in 2014 with the slogan "sabka sath, sabka vikas" (together with all, development for all).

In 2019, the BJP made nationalism and national security its main election planks, and in many ways the result was a referendum on this strategy, and more widely on his leadership.

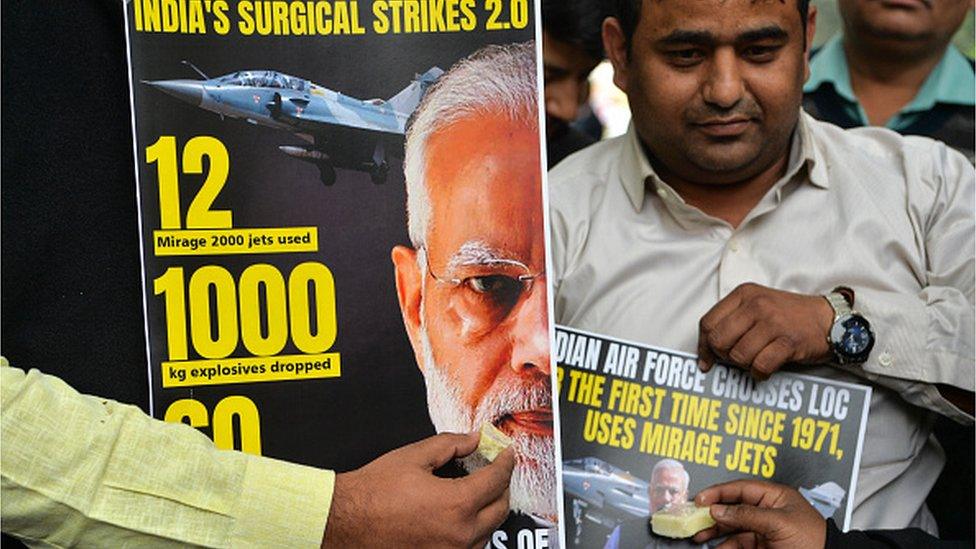

Many Indians celebrated Mr Modi's decision to send Indian jets into Pakistan in 2019

Mr Modi's first term as PM was a mixed bag of hits and misses amid concerns over rising Hindu nationalism, a slowing economy and violence against India's Muslim minority.

Landmark schemes his government launched include cheap cooking gas for the poor, a nationwide Goods and Services Tax, a health insurance scheme for the poor and a new bankruptcy and insolvency law.

His decision to promote and fund the construction of toilets in villages across the country to end open defecation was largely praised.

But demonetisation, as it was called, was viewed as a blunder by economists and could easily have backfired on him. Mr Modi claimed it was a success but in fact, his controversial decision to ban 500 and 1,000-rupee notes - as part of a crackdown on corruption and illegal cash holdings - badly hurt the economy, particularly the informal sector that largely relies on cash transactions.

Following his sudden announcement on 8 November 2016, the country was thrown into chaos. The following weeks saw a shortage of new notes and people struggled to deposit their old notes in the banks.

And the BJP's Hindu nationalist drive has also drawn criticism for Mr Modi. During his tenure, many BJP-governed states banned the consumption and sale of beef. The cow is considered holy by Hindus.

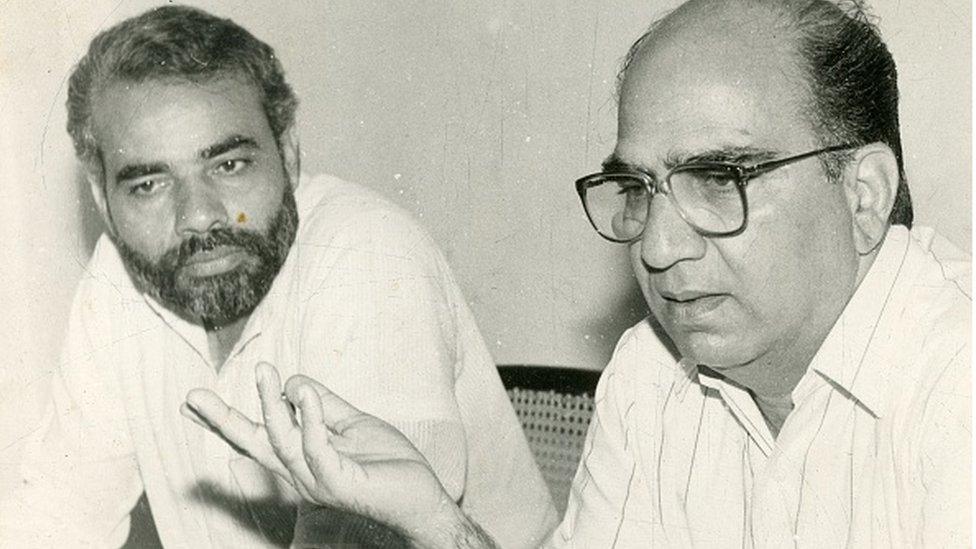

Mr Modi (left), then a BJP official, at a press conference in 1991

There was shock when a Muslim man was lynched in 2015 for allegedly storing beef in his fridge. Other Muslims have been attacked and beaten by cow-vigilante groups.

Mr Modi remained silent whenever such incidents happened, which was perceived by many as tacit support for rising intolerance.

But these issues were largely absent from the BJP's campaign pitch in 2019. Nationalism became the mainstay for the party's election strategy.

It stemmed from Mr Modi's decision to send fighter jets inside Pakistani territory in response to a deadly militant attack in Indian-administered Kashmir. This brought the two nuclear-armed states, which both claim Kashmir, to the brink of war.

Narendra Modi was born in 1950, the third of six children, to a family of grocers in what is present-day Gujarat.

He went on to serve as chief minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014, and became regarded as a dynamic and efficient politician who helped make the western state an economic powerhouse.

But he also is accused of doing little to stop the 2002 religious riots when more than 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed - allegations he has consistently denied.

After the riots, Mr Modi faced international isolation with the US denying him visas and the UK severing ties. However, his 2014 victory helped him get reintegrated into the global political mainstream.

He travelled far and wide, and addressed massive gatherings of non-resident Indians in the US and the UK. Analysts say it was his way of announcing his arrival on the global stage.

India's failure to promptly address the devastating second wave of Covid did not diminish Mr Modi's popularity

Mr Modi's rise from chief minister of Gujarat to India's PM was dramatic and took many by surprise.

A brilliant orator, the party's poster boy faced stiff internal differences when the BJP named him as its candidate for PM.

For years, his critics said he could never be prime minister because of the riots.

His personal life also came under scrutiny, with critics accusing him of deserting his wife, Jashodaben. It was only in the run-up to the 2014 elections that he publicly admitted for the first time that they were married.

He was 17 when the arranged marriage took place but the couple barely lived together and have been estranged for years.

Mr Modi has always avoided questions about his personal life amid suggestions he wished to appear celibate to his Hindu nationalist base.

Analysts say one reason for his strength remains the support he enjoys among senior leaders in the right-wing Hindu Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

The RSS, founded in the 1920s with a clear objective to make India a Hindu nation, functions as an ideological fountainhead to a host of hardline Hindu groups - including the BJP, with which it has close ties.

Mr Modi has a formidable reputation as a party organiser, along with a reputation for secrecy, which comes from years of training as an RSS "pracharak", or propagandist, analysts say.

He joined the Gujarat state unit of the BJP in the 1980s. His big break came when his predecessor as chief minister had to step down after an earthquake in January 2001 that killed nearly 20,000 people.

Related topics

- Published24 May 2019

- Published16 January 2024

- Published6 September 2023