Profile: Kailash Satyarthi

- Published

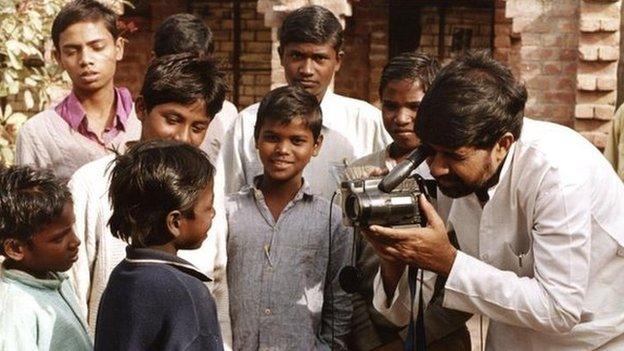

Kailash Satyarthi and former child slaves in India

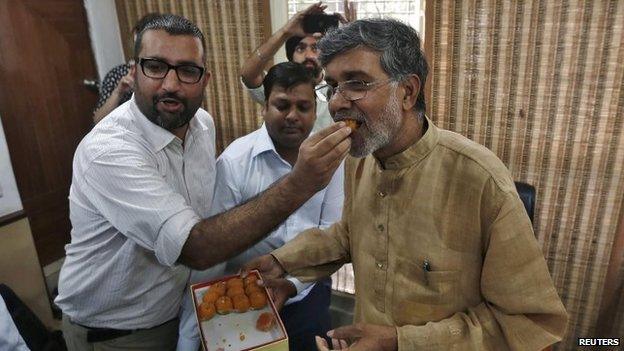

Indian child rights activist Kailash Satyarthi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his campaign for the rights of children and young people.

He was honoured along with Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai.

Accepting the prize in Oslo on 10 December, Mr Satyarthi declined to deliver a lecture, saying instead: "I represent here the sound of silence. The cry of innocence. And, the face of invisibility.

"I have come here to share the voices and dreams of our children, our children, because they are all our children."

Mr Satyarthi, who turned 60 in January, has long campaigned against child labour and rescued children from servitude. His efforts have seen tens of thousands of children rescued from hazardous industries and rehabilitated.

Mr Satyarthi, who says his mission is to "wipe away the blot of human slavery", has often staged dangerous and daring dawn raids on factories - sometimes manned by armed guards - which employed children.

Culprit companies, he said, included carpet makers, diamond miners and even firms that made footballs.

For his work, he has endured death threats and attempts at incarceration, and two of his colleagues were even murdered. But he continues with his campaign because, he has said, "somebody has to accept the challenge whatever dangers are there".

Meeting Kailash Satyarthi: Shilpa Kannan, BBC News, Delhi

In February, I met Mr Satyarthi at a shelter he runs just outside Delhi for rescued child workers.

He was sitting surrounded by anxious parents who had come from tea gardens in north-east India looking for their missing daughters.

He spoke patiently with each family, trying to devise a strategy to find their child.

"It's a risky job," he says. He is often threatened by unscrupulous middlemen who kidnap children to work in garment factories and was injured badly while rescuing child slaves from stone quarries in Rajasthan.

Helped by an army of volunteers, Mr Satyarthi has been campaigning against the exploitation of children for more than three decades.

I ask him if he has seen any improvement in the situation in all these years?

"It's only become worse," he says.

Nearly 30 years ago he left a promising career as an electrical engineer to set up Bachpan Bachao Andolan (Save Childhood Movement) and since then, by his own count, he has rescued more than 80,000 children.

He also heads the Global March Against Child Labour, which represents about 2,000 social groups and union organisations in 140 countries.

His campaigns over the years have ensured that India's carpet industry has stopped using child labour.

He also successfully led a movement to bring in a new law in 2012 to make employment of children under the age of 14 illegal - a law he considers his big achievement.

But India still has millions of child labourers - official estimates put the number at five million; Mr Satyarthi says it is as high as 60 million.

Many parents say poverty forces them to send their young children to work, while campaigners say child servitude is a reality in India and that it will continue.

But Mr Satyarthi has described that point of view as "absolutely pessimistic".

"We must all be totally against child labour. I want to see in my lifetime that there is no child slavery in the world," he told the BBC in an earlier interview.

The Nobel Committee made clear that this was why he was selected: "Showing great personal courage, Kailash Satyarthi, maintaining Gandhi's tradition, has headed various forms of protests and demonstrations, all peaceful, focusing on the grave exploitation of children for financial gain."

- Published10 December 2014