The Nobel's noble battle

- Published

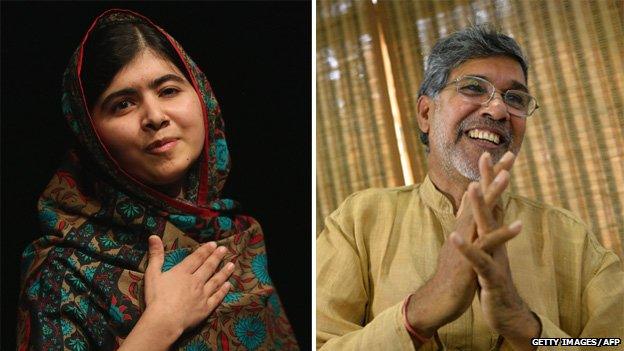

Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi jointly won the Nobel Peace Prize

At a time when news has been a dark canvas of conflicts and calamities worldwide, the announcement beamed a bright light through the gloom.

News of the Nobel Peace Prize did seem noble in its spirit, and symmetry.

An Indian and a Pakistani, a Hindu and a Muslim, a relatively unsung hero and a global star.

Nearly half a century separates two activists but their causes are now joined - their fight for children's rights.

Even the timing seemed perfectly placed.

Seventeen-year-old Malala Yousafzai, who defied Taliban threats to fight for every girl's right to be educated, heard the news in her own field of battle - a school.

Her chemistry class in the English city of Birmingham was briefly interrupted.

But the life-changing accolade did not stop physics and English lessons from going ahead on schedule.

Sixty-year-old Kailash Satyarthi, who's waged a decades long war against child labour and exploitation, was at his desk in his modest office set in the cacophony of crowded South Delhi.

Schoolgirls in Islamabad say they "are so very proud" of Malala Yousafzai

For a moment, there was an unusually uplifting buzz across the breathless timeline that is Twitter.

Hashtags of #India and #Pakistan had, in recent days, focused on new shelling, more suffering, across the Line of Control (LoC) in disputed Kashmir and the wound that has festered since the founding of two states.

Suddenly words like hope and pride took pride of place in 140 characters.

Congratulations whizzed back and forth across the borderless land of cyberspace.

But of course, no moment is pure or perfect, or lasts very long. And, on Twitter, no timeline is the same, as these Pakistani tweeters discovered.

Not so for @homakhaleeli:

Prizes, even as great as the Nobel Peace Prize, are only symbols that send signals.

But history is slowly made through both symbols and substance and Malala immediately seized the opportunity to create what would be another such moment.

She called on Pakistan's Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and India's Narendra Modi to travel to Oslo for the award ceremony on 10 December.

In her live televised speech, she informed the world that she had asked Mr Satyarthi to extend the invitation to his prime minister and she would do the same with hers.

The two leaders' first meeting in May during Mr Modi's inauguration had been analysed - down to every last detail - by the press, pundits and politicians.

An Oslo appearance would be much the same.

The politics of the prize is already unfolding in earnest.

Prominent journalist Jawed Naqvi, writing from New Delhi in Pakistan's Dawn newspaper, external, highlighted that by awarding this prize "at a time when their militaries were locked in a volatile spiral on the borders," many analysts were saying "the Nobel Committee has shone the torch on a more real enemy the countries jointly confront - jeopardized future for millions of their children."

Empowering

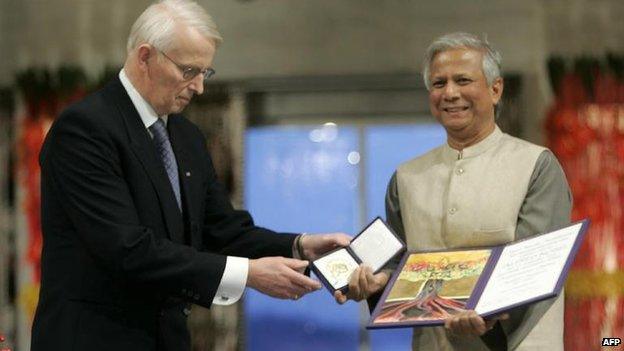

In 2006, when Muhammad Yunus of Bangladesh, the "world's banker to the poor" received the Nobel Peace Prize for founding Grameen Bank, it provoked a wave of discussion, and criticism, about what it takes to make peace.

Professor Yunus has earned international recognition for fighting poverty

The Nobel Committee sent a signal that year that fighting poverty, and empowering the poor, also played its part along with the traditional peacemakers and trouble shooters.

So too does empowering and enlightening the next generation.

The Nobel committee remarked that it is "a prerequisite for peaceful global development that the rights of children and young people be respected."

At a time when wars of our time, from Syria to Somalia, are highlighting the terrible price paid by the youngest and most innocent, two new Nobel laureates remind us there are ways to fight back - peacefully.

"I had a phone call from Kailash and we both spoke about how important it is for children to go to school" said Malala in the impressive impromptu address of a young woman who is already a global campaigner only two years after she narrowly survived a Taliban attack.

Malala Yousafzai said she was in a chemistry lesson when she heard the news

"We both decided to work together and also decided to try to build strong relations between both countries".

Mr Satyarthi was interviewed almost immediately on the BBC World Service and spoke of how he would work with Malala to "give voice to children who are never heard".

Bright moment

In more than three decades of dedicated activism against child labour, Mr Satyarthi has freed tens of thousands of Indian children from the medieval bondage perpetuated by many vested interests.

A blog published in the Times of India , externalasked why so few Indians "had any clue about who he was."

Now they do. We all do.

I also won't forget the moment when Muhammad Yunus took to the stage in Oslo in 2006.

A cold dark winter's day was brightened by the brilliant yellow and orange dress of Bangladeshi dancers, the warm proud smiles, and by his optimistic message that the war against poverty could be won.

The euphoria of the day quickly faded when a campaign was stirred against him when he returned home to Bangladesh.

But his determination and message still make a difference.

This year's ceremony is also certain to be another day of celebration and hope.

It may only last a moment. But in a world of dark threats, every bright moment matters.