The brave women fighting for Afghanistan's future

- Published

.jpg)

Rita Faizi (front) says she is proud to go to school

Nineteen-year-old Rita Faizi oozes confidence.

Taller than her classmates, when she waves a small Afghan flag, it flutters above a sea of white headscarves in the courtyard of the Zarghuna Girls' School in Kabul.

"I'm proud of my flag, and proud to go to school, so I can build my country," she declares as she approaches me at the start of the school day on a chilly winter morning in Kabul.

"Do you think a girl in Afghanistan can now do what she wants?" I ask this poised teenager, expecting another burst of youthful enthusiasm.

"Oh no, absolutely not," she shoots back, without a moment's hesitation. "If you want to go out, you can't go out alone. As you know, there are a lot of rapes."

Girls like Rita know sheer force of personality is no match for the very real threats to Afghan girls and women.

Listen to the voices of those who boldly speak out, and you're constantly struck by this double-edged sword that hovers, all too closely, over all their lives.

.jpg)

Education is key to advancing women's rights in Afghanistan

My recent trip to the Afghan capital was intended to build on the true stories in a new play "Even If We Lose Our Lives" commissioned by the human rights organisation Amnesty International.

But the three women featured in the script lost their voices in the more dangerous drama of daily life.

A gynaecologist who only uses her initial Dr D, as well as school headmistress Parween, were forced to go into hiding because of threats linked to their work. Women's activist Maneesha also faces risks.

So, I went in search of other voices for our programme "Speaking out, Losing Lives" for BBC Radio 4 and the World Service, produced by Beaty Rubins.

At Kabul's Rabia Balkhi hospital, I found a more reassuring window on a women's world.

Nurses in lilac

Well-educated Afghan women doctors are in charge, trained female nurses attend to female patients.

In the hallway I run into a gaggle of young women in lilac-coloured medical coats and caps. They've come to the capital from remote impoverished areas of Daikundi province to train as community midwives.

Meela Sarwar, who heads the training programme, is also brimming with confidence, and the conviction of her mission.

"After two years we will send them back to their own areas, where there is no clinic, no nurse, no doctors, they are the nurse, doctor, midwife, everything," she tells me.

.jpg)

Training programmes, like those run by Meela Sarwar, are helping to push down the maternal mortality rate

Afghanistan's maternal mortality rate, once one of the highest in the world, is now said to be inching down, partly because of the growing presence of competent midwives, and more clinics and better practises in some areas.

A comforting sense of order and routine is suddenly shattered when an elderly woman holding a baby swaddled in a tiny white blanket hurries toward us.

"Girl or boy?" I ask as she approaches.

"Dead," replies a grieving grandmother as she draws her arms more closely around the stillborn child. The distraught mother then rushes out the door in her all-enveloping blue burka. The garment, which only reveals a woman's eyes, cannot conceal her grief.

In a country where many women's main role in life is simply to bear children, it's a tragic turn.

Meela shakes her head. "She waited seven years to conceive but then waited through nine months of pregnancy before she came to the hospital to see us."

It's still the story of all too many women.

Children attacked

Female professionals in hospitals are also fighting on another front. A new department has been established to tackle gender-based violence.

"We deal with many cases - physical trauma, emotional trauma, sometimes sexual trauma including rape cases," Dr Aweed Dehyar, head of Rabia Balkhi hospital, explains as she sits in her office in her crisp white medical coat and cap.

.jpg)

Dr Aweed Dehyar says that children as young as three have faced gender-based violence

She tells me about cases involving teenagers and even children as young as five, or even three years old. "Are there many cases that age?" I ask.

"I think one case in three months but in Afghanistan, all cases don't come to the hospital. Out of ten cases, maybe one comes here."

Last month the case of three-year-old Neelofar, attacked by an 18-year-old boy, shocked many. But women's activists hailed the fact that at least it came to light.

There are more legal weapons to protect Afghan women now. The landmark Law on the Elimination of Violence against Women went into effect in 2009 but, aside from a few exceptions, most evidence shows it is largely unimplemented and unenforced.

Defiant schoolgirls

To advance women's rights, education is fundamental which is why the scenes at schools like Zarghuna in Kabul are so significant.

When the impressive Rita Faizi takes me along to her English class, I ask what seems like a whole classroom of confident girls whether they fear the return of the Taliban which once banned their education.

"With our knowledge, with our education, we want to defeat them," rises the defiant young chorus from the neat rows of wooden desks.

Students at Zarghuna girls' school were brimming with confidence - and defiance for the Taliban

Last week, at the London Conference on Afghanistan, their newly elected President Ashaf Ghani made it clear that empowering women is one of his top priorities.

When I ask him whether he's ahead of his time in his still deeply conservative country he insists: "We have gone back in time. I just want to give opportunities to Afghan women that my grandmother had. What's wrong with that?"

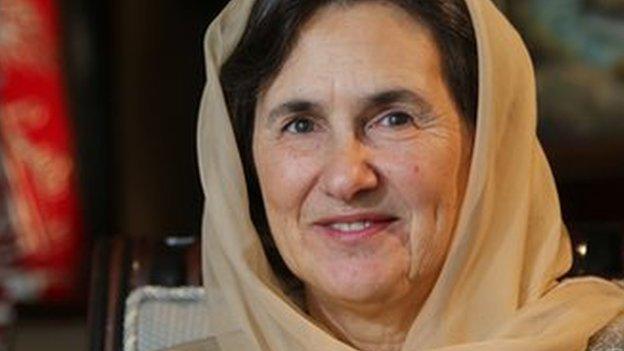

In Kabul, I meet his wife Rula Ghani in her new office inside the heavily fortified palace for the first First Lady most Afghans have known.

"You know the expression, show don't tell?" Lebanese-born Rula Ghani asks. "I think my husband is showing in the way he's allowing me to proceed that women can have a role."

Now, as Afghanistan enters a new political chapter, millions more men, and women, are being called upon to do the same.

Speaking out, Losing Lives is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 20:00 GMT on Monday 8 December and 15:00 GMT on 31 December. You can also catch it online.

- Published21 October 2013

- Published15 October 2014

- Published4 April 2014

- Published28 January 2014