How Pakistan's women are punished for love

- Published

In a country fighting to preserve patriarchal and tribal traditions, Pakistan's women can face brutality - and even death - if they fall in love with the wrong person.

Arifa, 25, dared to stand up to her family, running away with the man she fell in love with and secretly marrying him.

The following day in a busy street in Karachi, Pakistan's most populous city, her male family members surrounded the newlyweds and, at gunpoint, dragged Arifa away.

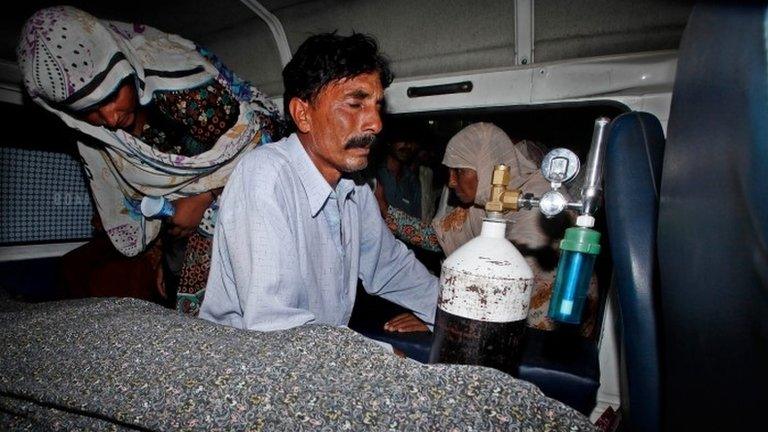

It was five days before her husband, Abdul Malik, heard any news of his wife.

"I got a message that she had been murdered. That was the most difficult day of my life," he tells me, holding back the tears. "After great difficulty I managed to establish that my wife was alive and had been hidden somewhere."

Fearing for his life, Mr Malik has lived in hiding for three months.

"In Pakistan, love is a big sin. Centuries have passed, the world has made so much progress - men have reached the heavens. But our men are still following age-old customs and traditions from the dark ages," he explains.

It is these traditions and customs - which focus on denying women freedom - that have growing acceptance in Pakistan and are encouraged by hard-line religious scholars.

'Honour crimes'

The rule of law is often ignored.

This is a world where a woman has few rights in practice - she is the property of her family until she marries.

Then ownership passes to her husband's family, with the risk of death if she brings dishonour to the family.

This year alone, more than 1,000 women have been murdered for so-called honour crimes - and these are just the ones of whom the authorities are aware.

In May, the case of the young, pregnant woman Farzana Parveen shocked the world. She was stoned to death by her family for marrying the man she was in love with, rather than the man they had chosen for her.

Human rights activists protest against the killing of pregnant woman Farzana Parveen in the city of Lahore

What was most shocking was that it happened outside Lahore's high court, in front of policemen and passers-by.

In November, following worldwide media attention, Ms Parveen's father, brother, cousin and former fiance were all found guilty of murder and given the death sentence, while another brother got 10 years in jail.

But more often than not, those who commit these brutal acts against women are never charged, protected by tribal laws.

Some hard-line religious scholars believe that only through the killing of an offending family member - usually a woman - can honour be restored to the rest of the family and tribe.

The most surprising point is that few people in Pakistan nowadays are willing to challenge these tribal traditions and customs. In fact, according to a recent survey from the Pew Research Centre, external, an overwhelming majority of Pakistanis support the full implementation of Sharia - Islam's legal system.

'Stoning and lashes'

In the backstreets of Karachi, I find a madrassa where thousands of boys and young men receive their religious instruction. I want to ask the local clergyman about his thoughts on adultery, for which women have also been murdered in "honour killings".

"The punishment is what is prescribed in Sharia, which is stoning and lashes," the mullah tells me.

The mullah says peace in Pakistan "can only be achieved through the imposition of Sharia law"

One of his pupils backs his teachings: "Once it is proved, in Sharia, the punishment is either lashes or stoning."

At this madrassa, I find little sympathy for women who stray - punishing adultery is a clear-cut duty.

But what does the country's law say? In 1979, Gen Zia-ul-Haq, Pakistan's military dictator, introduced the so-called Hudood Ordinance - a controversial set of laws that attempted to Islamise Pakistan. Among other things, it made adultery punishable by stoning and lashing.

In 2006, the then President, Pervez Musharraf, tried to liberalise some of these laws to protect women, but the enforcement of his reforms has been limited and adultery is still a crime.

'My husband kicked me out'

Karachi's central prison for women is where many of those accused of adultery end up.

Sadia is 24. She arrived at the prison four months ago after her husband of nine years accused her of sleeping with another man. She is still awaiting trial.

"My husband divorced me, beat me and then kicked me out of home," she explains. "Then he went to the police and told them that I'd run away with another man. In reality he and his family beat me and kicked me out."

Some Islamic hardliners believe imprisoning women accused of adultery does not go far enough

Sadia tells me she does not have access to a lawyer and is not sure when she will be able to leave. At the time of my visit, there are 80 women in the prison - many have no idea why they are there and end up languishing in jail for years without trial.

Some of the more lucky women end up at a handful of shelters across the country.

I travelled to the Edhi shelter for women, a heavily guarded compound in one of the most notorious and dangerous neighbourhoods on the outskirts of Karachi, known for its Taliban sympathies.

Most of the women here have run away from abusive relationships or have been thrown out on to the streets by their families.

The women live at the Edhi shelter peacefully, sharing chores, helping with the cooking, cleaning and taking care of each other's children. There are never any questions asked about why a woman has sought refuge at the home.

There is one strict rule that everyone abides by - nobody is allowed in without the say of the women, including the authorities.

"If she is having an affair outside of here, we don't care, we don't ask. She can stay as long as she likes," Samina, a volunteer at the shelter, tells me. "If her family come to take her and she goes willingly, then she is free to go."

What if the police are after her for adultery charges, I ask. "No, we won't hand her over to the police," says Samina.

The Edhi shelter provides women safety from abusive relationships, and a place to stay if thrown out of the family home

'My children would scream'

Draped in a red headscarf, Ayesha says she has left her home five times with her two young children, fleeing to the safety of the shelter.

Each time, her husband comes to collect her. But she tells me the abuse and torture she is subjected to when she returns with him force her to run away again.

Ayesha says her husband accuses her of having an affair. "My husband would lock me up and then he would start to beat me, beyond any limit, forcing me to say that I was having an affair.

"My children would scream, 'Please someone save our mother.' But no-one would listen, no-one would come."

Ayesha tells me she has no intention of returning to her husband now. Although the future remains uncertain for her, she says she feels lucky to be alive.

Despite a growing middle class, attempts at modernity and secular condemnation, combating ingrained institutional misogyny has become increasingly difficult in Pakistan.

In a society fighting to preserve patriarchal and tribal traditions, women face brutality and gender-based violence in both urban and rural districts.

And as religious fundamentalism continues to gain ground, the freedoms of women are increasingly attacked.

BBC Our World's Pakistan's Women - Punished For Love broadcasts on the BBC News Channel at 21:30 GMT on Saturday 13 and Sunday 14 December - or catch up online.

Internationally, you can see the programme on BBC World News on Saturday 13 December at 11:30 GMT and Sunday 14 December at 17:30 GMT.

- Published19 November 2014

- Published29 May 2014

- Published25 July 2013