Mutual antipathy hampers Pakistan control of militants

- Published

Lighting a candle in memory of those who died in the Peshawar school attack

The vast majority of Pakistanis may be united in grief for the school children murdered in Peshawar - but many say they still don't know who carried out the attacks.

For the media - both in Pakistan and abroad - the issue is clear enough: the Pakistani Taliban did it.

Not only has the organisation claimed the attacks. but the intelligence service ISI also recorded real time messages from handlers to the gunmen in the school.

Those messages, the ISI has told journalists, came from the phones of Afghan-based, Pakistani Taliban organisers.

But in Peshawar even people who witnessed the attack hesitate to blame the Taliban by name.

They not only fear reprisals but are also following the hesitancy of a political elite that remains largely unwilling to name and condemn the Pakistani Taliban in unequivocal terms.

Even on the day of the Peshawar school massacre, the Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, failed to condemn the Taliban by name. He referred only to "terrorists".

An alternative narrative relating the school attacks is already emerging: rumours are circulating on social media and on the streets that it was the work of Indian or Afghan intelligence agencies.

The fact that some of the attackers appear to have come from Central Asia lends weight to suggestions that there was a foreign hand in the attacks.

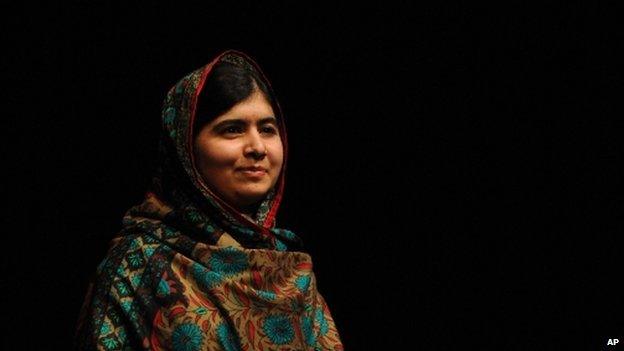

The emerging analysis of the school massacre echoes that which occurred after the shooting of Malala Yousafzai.

Initial shock eventually transformed to the almost mainstream view in Pakistan today that Malala is a western stooge.

That's not to say the school massacre has had no impact on public opinion.

When a radical cleric attempted to justify the attack this week, protestors gathered outside his mosque in Islamabad chanting anti Taliban slogans.

That's new. But there is still no big name politician prepared openly to lead people with that point of view.

Distrust and division

That is in part because the Pakistan's civil and military elites are so divided and dysfunctional.

The politicians have a number of reasons for leaving the fight against the Pakistan Taliban (TTP) to the army.

Nawaz Sharif has a cool relationship with the army

Privately, government ministers argue that the army's total control of security policy means it is unreasonable for the generals to expect the civilians to take responsibility for what the army decides to do.

The politicians are anyway deeply suspicious of an army that has frequently mounted coups to overthrow elected governments.

The current Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, was kicked out of power, put in a dungeon and then exiled by the last military ruler Pervez Musharraf.

Sharif believes that despite his overwhelming popular mandate the army has never accepted his political comeback, external in 2013 and is once again plotting to remove him from power.

In addition many politicians fear the Taliban.

The one party to attempt a political challenge to the Taliban in recent years, the Pashtun nationalist ANP, has faced relentless attacks on senior party cadres.

The ANP's stand was also politically disastrous.

Far from perceiving the party as a valiant defender of liberal values, the electorate concluded the ANP was weak and unable to defend itself. The party now has just one member of the National Assembly.

Mutual feelings

But if the politicians loathe the generals, the feeling its entirely mutual.

Many officers view Pakistani ministers and parliamentarians as corrupt and depraved, unwilling to put aside their lust for money and to focus instead on the plight of the country.

There is deep resentment in the army that when soldiers die in the fight against the Taliban, ministers do not make public speeches appreciating their sacrifices.

Ministers rarely go to military hospitals to comfort soldiers injured in the fight against the Taliban.

It's estimated as many as 50,000 Pakistanis have been killed in political violence since 9/11.

Members of the security forces including both the army and the police account for around 10,000 of those deaths.

Successive army chiefs have said that if they are to win the war against the TTP they need the politicians to lead Pakistani public opinion to support their military's campaign.

Militant spectrum

But while the army complains about the politician's failure to take clear line against the Taliban, others wonder how clear cut army policy is.

There are now well over 30 significant militant groups with a presence in Pakistan, each with different leadership structures, funding arrangements, ideological foundations and political goals.

The three most powerful are the Afghan Taliban, the TTP and the Punjab-based Lashkar-e-Taiba which concentrates its efforts on Kashmir and India.

All seven attackers were killed during the eight-hour siege at the school

Given the scale of problems faced by the Pakistan army, it is perhaps not surprising that it has decided to fight only those groups that are directly confronting it.

That means many Pakistani based militants are free to organise attacks on targets outside of Pakistan. For example, the anti Indian Lashkar-e-Taiba operates in Pakistan with little difficulty.

Allegations of collusion

Western and Indian critics of the Pakistan army believe the army policy in fact goes much further.

They allege that the army does not just give some groups a free pass but, in fact, effectively controls them and uses them to advance the military's foreign policy goals.

By backing the Afghan Taliban, for instance, it ensures that the power of what Pakistan considers hostile elements such as the Tajiks is kept to a minimum or by backing Lashkar-e-Taiba it can advance the Pakistan cause in the disputed region of Kashmir.

The military strongly denies those claims.

While the army clearly does distinguish between different militant groups there can be no doubt that for some years now it has been confronting the TTP.

And its sometimes brutal campaign has had considerable success.

In 2009 the TTP had a high degree of control of 18 administrative units in north west Pakistan including some entire tribal areas.

The army campaign of the last few months pushed the TTP out of its last major redoubt, external in Pakistan; North Waziristan.

The TTP are now hemmed into to small pockets of territory in remote areas near the Afghan border, and its leadership has been forced to take refuge in Afghanistan.

Afghan plea

Soon after the school massacre the Pakistan army chief Raheel Sharif went to Kabul to demand action against the Afghan-based TTP leader Mullah Fazlullah.

Some believe Malala Yousafzai is a western stooge

He took transcripts of the intercepted school massacre conversations with him.

But General Raheel Sharif's request is almost certain to run into a significant obstacle.

In return for moving against the TTP leadership on its soil, Afghanistan will expect Pakistan to move against any Afghan Taliban leaders sheltering in Pakistan.

It is believed that for many years now senior Afghan Taliban leaders have sought sanctuary in and around the Pakistani city of Quetta.

So once again Pakistani regional goals could undermine its fight for stability at home.

The army's desire to win more influence in Afghanistan through the Afghan Taliban could jeopardize its victories at home against the TTP.

- Published7 November 2014

- Published3 May 2011