Pakistan school attack: Blazers flecked with blood

- Published

The attack on the army school in Peshawar shocked and outraged the world

The smallest of uniforms can be the most powerful of symbols.

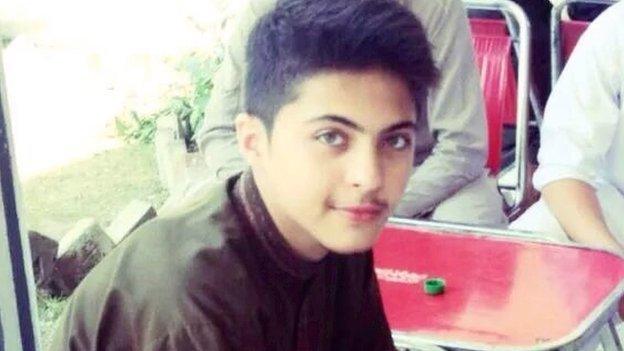

In Peshawar, the boys who survived last week's massacre defiantly wear their emerald green school blazers with blackened spots of blood.

"You can take down my school, you can take down my teachers, you can kill my brothers, but you cannot take away my identity," Aakif Azeem, 18, an aspiring astrophysicist, declares on his Facebook page.

The bloodstained blue and white uniform of the most famous Pakistani student is now mounted behind glass in the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo to honour her life-threatening battle for education.

When the Taliban came for 15-year-old Malala Yousufzai in October 2012, they boarded the school bus, shouting "Who is Malala?" Then they opened fire.

When gunmen stormed into classrooms in the Army Public School in Peshawar, they demanded, "Who are the boys who belong to military families?"

The massacre also sparked condolences from leadership and citizens in India with which Pakistan has a troubled relationship

Then "they stood them in front of a wall..they killed them, all of them", Aakif recounted to my colleague Owen Bennett Jones.

Every day since this coldblooded murder of 141, including 132 children, the overwhelming sadness and shock has fuelled anxious questions.

Will this be a turning point? Is this the attack to end an all too long and bloody history of attacks on schools, markets, churches and playing fields, as well as assaults on those who dare speak out against this carnage? Is this massacre, this moment, different?

"This is an unspeakable atrocity," is how journalist Omar Waraich summarises the views he has heard across what he calls a "horror-hardened" society. "We never imagined a war against children was ever possible."

Can the shock of so many innocent children cut down in their uniforms be the moment that shakes adults who wear the uniforms of security forces or carry titles with real power to change course?

One week on, Pakistanis are not sure. They have been here too many times before. And the answer to this simple searching question is neither simple nor straightforward.

Malala Yousafzai broke down in tears when she saw her bloodstained school uniform again at the Nobel Peace Center

More than 40,000 have been killed in brutal attacks by militant groups since 2001. That year was also meant to be a turning point, a watershed, after the attacks of 9/11 forced Pakistan to join what was called a global "war on terror."

Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was quick to call this Peshawar massacre "Pakistan's 9/11… a game changer". He promised a strategy against this terror within a week.

A six-year moratorium on the death penalty has been lifted. Security sweeps are under way. Taliban positions are under attack by the military.

And in a country where citizens from all walks of life often show great solidarity at moments of national tragedy, there has been an unprecedented response.

Crowds are small but brave and growing at anti-Taliban protests in major cities, outside mosques and on the streets.

Cyber battles are being waged on social media with a blizzard of hashtags - #nomore, #neverforget and #reclaimyourmosques.

And politicians have, for the moment, put aside more petty political battles to join forces in an existential fight for Pakistan.

But, as a new narrative emerges from this revulsion and resolve, old ones have already returned to inhabit their well-established space.

Mourners have gathered a week after the massacre in Peshawar to remember the children and staff killed

Former cricketer-turned-politician Imran Khan returned to Peshawar on the day of the attack

Pakistan's former president Pervez Musharraf also took to the media to denounce the attack

Former military ruler Pervez Musharraf took to the airwaves to point to an Indian hand in this latest atrocity. Other well known voices denounced Western wars and defended one militant group or another.

And the Pakistani Taliban are not silent or shirking from the possibility of even more bloodshed. Now there are reported threats against children of politicians, against protesters.

The Taliban, known by their initials TTP, described the Peshawar attack as revenge for the military's recent offensive in the tribal area of North Waziristan, widely seen as the epicentre for many extremist groups.

Army action had emerged after years of pressure from within Pakistan, from neighbouring states, from Western capitals.

But this still was not the moment of reckoning in a decades-old strategy of sheltering and supporting armed groups to fight proxy battles against arch-enemy India and an emerging order in Afghanistan.

I have heard explanations, over many years, from senior Pakistani soldiers about the need to avoid making enemies of forces which did not endanger Pakistan itself. They also spoke of the imperative for a national consensus to bolster any major fight.

Now, Prime Minister Sharif insists there will be no distinction between "good and bad" Taliban.

"Pakistanis are united against terrorism," cautions prominent Pakistani columnist Cyril Almeida in the UK's Guardian newspaper, external, "but not on who the terrorists are."

Most of the 141 people killed in the Peshawar massacre were schoolchildren

The security challenge is huge and complex, and must draw in Pakistan's neighbours. And wars waged in khaki must be fought alongside other kinds of battle for those in the next generation who still don school uniforms, and those who do not.

Most recent published figures highlight how, out of 52 million Pakistanis aged between five and sixteen years, 25 million are not in school.

A million are schooled only in madrassahs often run by hardline Islamist preachers.

"Just adding maths and cooking classes to madrassahs' curriculum won't fix the problem," says former diplomat Mosharraf Zaidi, who heads the Alif Ailaan education campaign. "There's an all-pervasive tolerance of hateful speech that's become institutionalised within the state."

"This will severely test a state that even has trouble collecting taxes and providing electricity," reflects Omar Waraich.

On 5 January, schools are set to reopen. Some students are already vowing to return to class, although some parents may understandably hold their loved ones back.

When Malala Yousufzai stood in front of her school uniform she lent to the Nobel Peace Center, she broke down in tears and was comforted by her fellow laureate from India, Kailash Satyarthi.

Hours earlier, when she accepted her Nobel Peace Prize, she made an impassioned call for action: "Let this be the last!"

A week later, there were floods of tears and streams of blood in a school in Peshawar.

- Published22 December 2014

- Published19 December 2014

- Published17 December 2014