Japan hostage killing: Critical test for PM Shinzo Abe

- Published

PM Shinzo Abe was visibly moved by the news, but some Japanese have been highly critical of his position

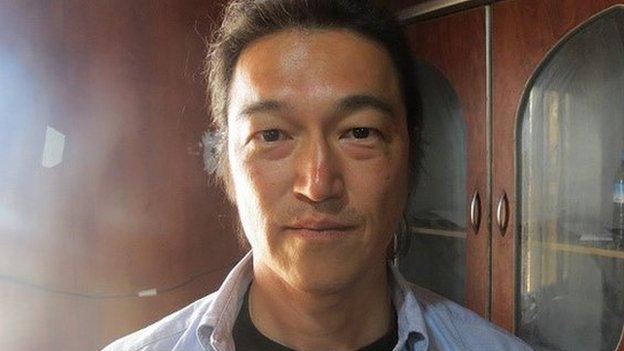

Sunday's announcement of the killing of Kenji Goto, the second of two Japanese hostages captured by Islamic State (IS) militants, represents a major political challenge for the Japanese administration of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

It also raises important questions about the future security of Japanese citizens at home and abroad, the degree of Japanese public support for the country's increasingly proactive foreign policy, and the prospects in 2015 for government legislation to allow Japan's Self-Defence Forces (SDF) to play a more active overseas role.

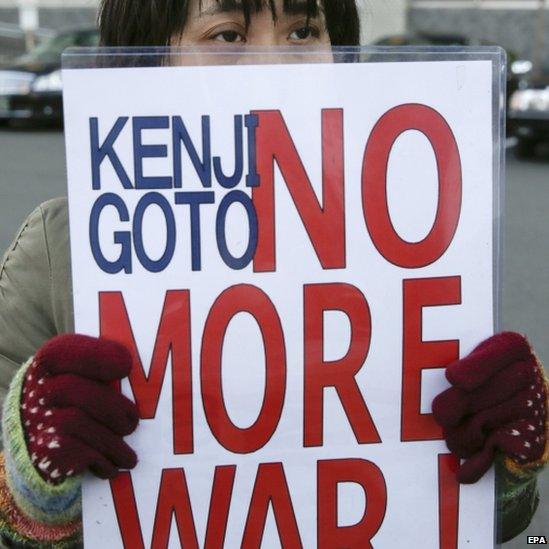

While there was widespread shock at the two deaths, Japanese public reaction to the hostage crisis in general has been mixed.

Many Japanese responded to the humanitarian dimension of the crisis, using social media to express their solidarity with the victims and their families.

Some lobbied the government to rescue the two men by acceding to the hostage-takers' demands, either through the payment of a $200m (£133m) ransom or by engineering the release of Sajida al-Rishawi - a former al-Qaeda activist imprisoned in Jordan for her role in a bomb attack on a wedding in the country in 2005.

Others, by contrast, have been critical of the two captured Japanese, accusing them of a lack of responsibility in travelling to Syria in the first place, suggesting that they had needlessly endangered themselves and wider Japanese interests, and implicitly arguing that the government had little obligation to prioritise their case.

'Not giving up'

Neither the willingness to bow to the terrorists' demands nor the desire to distance Japan from involvement in the politics of the Middle East is without precedent.

The Japanese public has often been allergic to the idea of even minimal Japanese involvement in overseas conflicts

Japan has paid ransoms in the past, most notably in 1977, when the administration of Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda paid $6m for the release of Japanese air passengers captured by Red Army terrorists.

Also, the Japanese public has often been allergic to the idea of even minimal involvement in overseas conflicts, reflecting the pacifist ideas of the country's 1947 Constitution and an arguably misplaced notion that Japan has been relatively immune to challenges to its national security.

In recent years, Japan's governments have incrementally - but deliberately - moved away from this low-profile and relatively detached foreign policy.

Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi provided strong rhetorical, logistical and financial support to the US-led allied reconstruction effort in Iraq, and in 2004 rejected terrorist demands to withdraw peacekeeping SDF forces from Iraq, prompting the execution of Shosei Koda, a Japanese civilian.

Mr Abe has reinforced this approach, making it clear in unusually forceful language that "Japan will not give in to terrorism" and that the country will "work alongside the international community to make them [the terrorists] pay for their sins".

He has also made it clear that Japan will continue to provide substantial economic and humanitarian aid to countries in the region caught up in the struggle with IS.

Posture of unity

Shortly before Mr Goto's death, some Japanese opposition politicians implicitly criticised the government, suggesting that Mr Abe's announcement of a $200m aid package to the region on 17 January during his visit to Cairo may have triggered the hostage crisis by aligning Japan too closely with the wider anti-IS initiative.

Kenji Goto's mother, Junko Ishido (r): ""I can't find the words to describe how I feel about my son's very sad death."

Such claims of government failure seem overstated, at least in terms of Tokyo's immediate public reaction to the crisis. Overall, Mr Abe's approach has been focused and proportionate.

Temperamentally, Mr Abe has been keen to adopt a tough position, consistent with the more proactive foreign and security policy that he has been developing since 2012.

He has also been determined to align Japan firmly with the country's most important ally, the US, which - along with the UK - has publicly argued against any concessions to terrorist demands.

Following the 20 January announcement by IS that it planned to kill the two hostages, Mr Abe convened the country's security council and established a crisis management headquarters to work with key countries in the region - most notably Jordan and Turkey - to resolve the conflict, via discussions with tribal groups in Iraq or possibly through indirect links with the hostage-takers themselves.

In maintaining a posture of unity with the US in not bowing to terrorist demands out of fear of prompting future abductions, Mr Abe appears to have had little choice but to act in the way he has.

Public ambivalent

His government may, however, find itself criticised for not anticipating the latest crisis.

Unconfirmed reports in the Japanese media claim that the government may have known as early as November about the seizure of the two hostages.

The related suggestion that the government may have attempted to silence Japanese media reporting these details in order to negotiate behind the scenes for their release may prove politically explosive for Mr Abe personally and the government as a whole.

For the immediate future, the prime minister has made it clear that he will attempt to enact legislation, allowing the SDF to participate in efforts to rescue endangered Japanese citizens abroad.

The changes are also arguably a necessary response to an increasingly dangerous international environment, and the government almost certainly has enough votes in both houses of parliament to pass the new measures.

Yet it is uncertain whether the Japanese public, which remains ambivalent and nervous about the idea of Japanese forces being involved in conflict situations, will be happy to support this new, more expansive role.

There is also concern in some quarters that Mr Abe may also be pushing a wider programme of constitutional change and that any new legislation will be the pretext for an agenda that includes a more contentious policy of historical revisionism alongside the more narrowly defined security policy.

Against this background and in the face of widespread shock at the tragic and very public deaths of two Japanese civilians, Mr Abe will need to be politically astute to bring the Japanese public with him, while also demonstrating that he enjoys the necessary trust and skill required to keep the country and its citizens safe.

- Published1 February 2015

- Published1 February 2015

- Published31 January 2015

- Published2 August 2014