Lifeless Uzbek election hides power struggle

- Published

Large crowds are rare - the authorities have cracked down on religious activity outside state institutions

It's one of the world's most predictable elections, but Uzbeks gave their long-term leader something of a wake-up call in the run-up to Sunday's vote.

Authoritarian President Islam Karimov can still count on a fourth consecutive victory. But an unprecedented mass gathering in honour of an Islamic scholar who died earlier in the month rattled a regime which keeps a tight grip.

The event - right in the middle of the campaign - suggested that people's acquiescence cannot be taken for granted.

In startling contrast to poorly-attended election events, huge crowds flooded the streets of the capital, Tashkent, on 11 March following the death of Sheikh Muhammad Sodiq Muhammad Yusuf. Traffic came to a standstill as people paid their respects in a spontaneous outpouring of grief.

It was a highly unusual scene for a country where public gatherings are tightly controlled.

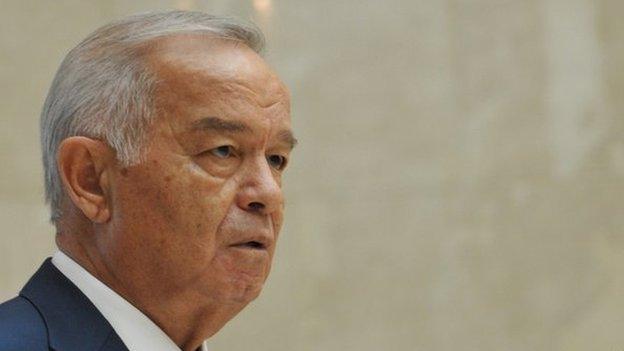

President Islam Karimov has been in power for over 25 years

The authorities have an uneasy relationship with Islam, flourishing since independence, and the state has cracked down hard on anyone it suspects of militant tendencies.

John MacLeod, Central Asia analyst of the Institute of War and Peace Reporting, thinks the mass gathering was born not just from religious sentiment.

"I think it's not necessarily about political Islam, but it shows that people are not completely cowed," he says. "They care about their livelihoods, they care about their children's future like everybody else and they are very disappointed and disillusioned in the political and judicial systems."

Many Uzbeks suffer economic hardship and millions have been forced to seek work as migrant workers abroad, mainly in Russia. But with the Russian economy struggling, an increasing number have returned and are unemployed, meaning vital remittance payments have dwindled.

John MacLeod says people have little faith in the state and its institutions, and no means to express their disappointment.

"There are no political parties or proper trade unions, there aren't the normal channels for people to vent their unhappiness and communicate it to the authorities and get something done about it."

'Peace and prosperity'

The election campaign itself has been a lifeless affair, as many would have predicted.

Mr Karimov is seeking a fourth mandate despite the constitutional two-term limit

Election posters on the streets of Tashkent look almost identical, featuring portraits of the various candidates and largely interchangeable slogans.

Mr Karimov's poster bears the call: "Our goal is peace, prosperity and democratic modernisation for the country."

The slogan of one of his supposed rivals, Akmal Saidov reads: "From national revival to national development."

It's not stuff to get the heart racing.

The other candidates have been full of praise for President Karimov

What's more, not a single candidate competing with Mr Karimov voices even a hint of criticism of the incumbent and his record. Instead, most have been praising Mr Karimov's achievements.

Mr Saidov, for example, drew parallels between the current president and the medieval conqueror Tamerlane, who is revered as Uzbekistan's national hero.

All candidates are current officials: A former teacher-turned-senator, a geologist-turned-environmental official and a lawyer who now heads the national human rights body.

John MacLeod says it's reminiscent of the way Soviet leaders used to orchestrate a semblance of legitimacy.

"Even in the Soviet period there were always elections. Single candidates would be put forward and people would be bussed in to take part," he says. "So it is the inertia of that Soviet tradition, that somehow - if you hold elections - that makes it the people's choice."

Sister wars

But while the election process grinds on, observers say there is a very real battle for power being fought behind the scenes.

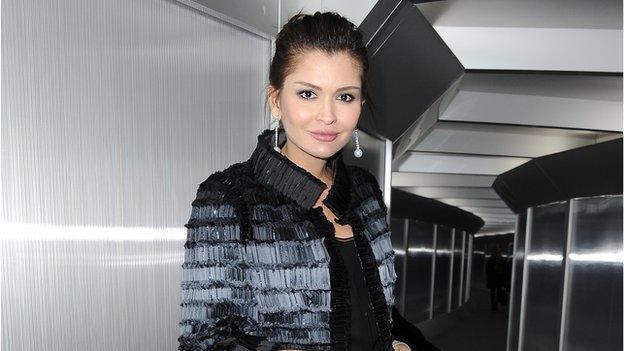

Lola Karimova says she's not interested in politics

The debate over who will succeed the 77-year-old president has been raging for years.

The theory that his powerful elder daughter Gulnara was being groomed for the top post fell apart last year when her business empire was dismantled.

Ms Karimova, whose exploits as a pop star and fashion designer were ever-present in the Uzbek media, was put under house arrest after a spectacular and very public row with her mother and sister, fought out on social media.

The scandal has been widely interpreted as both a sign of political rivalries breaking into the open and an indication that President Karimov may be losing his grip.

Many analysts say he has found himself increasingly isolated, not always fully informed and with no obvious successor in place.

So while the presidential election seems a routine exercise, the post-Karimov era is more unpredictable than ever.

Who wields the real power?

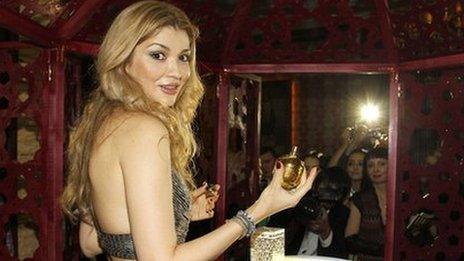

Gulnara Karimova was put under house arrest after falling out with members of her family and the Uzbek elite

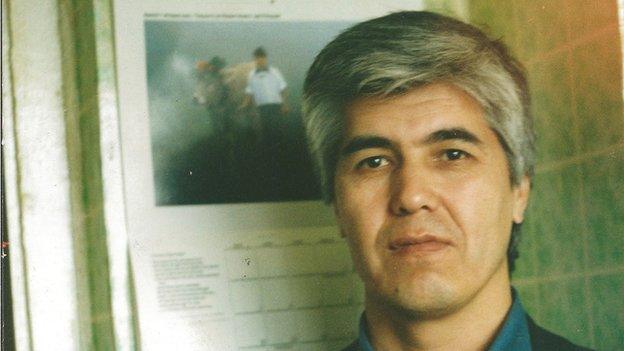

Rustam Inoyatov, 70, is chairman of the powerful SNB security service and one of the longest-serving members of the Uzbek political elite. A leaked US diplomatic cable from 2008 described him as a "key gatekeeper to President Karimov" and his style as alternating between "engaging and menacing". Mr Inoyatov is regarded as the main instigator behind moves to sideline President Karimov's once-powerful daughter Gulnara.

Shavkat Mirziyoyev, 58, is the country's longest-serving prime minister with a reputation for being ruthless. He has denied past allegations of mistreating subordinates, telling a BBC journalist in 1998 that it was "not his style to beat someone". Mr Mirziyoyev is camera-shy, with sources at state TV saying he has given a personal order not to show him on TV so as not to irritate President Karimov. He is reported to have close links with powerful oligarchs and is in charge of the country's key agricultural sector including the cotton industry, which has been criticised for the use of child and forced labour.

Rustam Azimov, the 56-year-old finance minister, is the most recognisable face of the Uzbek government abroad. Born into a family of respected academics, he chairs the US-Uzbek inter-governmental commission and is described in the Russian media as Washington's preferred successor to President Karimov. Fluent in English, he is believed to be in favour of more liberal economic policies. He is credited with the Uzbek government's attempts to open up the economy in the late 1990s. Some analysts describe Mr Azimov as a rival to the prime minister.

The Karimov family. The president's elder daughter, Gulnara, was long considered a potential successor, drawing on an extensive business and media empire. But after an apparent falling out with her father in 2013 Gulnara was sidelined and has been under house arrest for a year. She also fell out publicly with her sister, Lola Karimova-Tillayeva, whose profile has been on the rise. However the younger sister says she has no political or business ambitions.

Pahlavon Turgunov contributed to this report

- Published23 March 2015

- Published9 March 2015

- Published16 January 2014

- Published20 November 2013

- Published26 September 2014

- Published8 May 2018