Profile: Lashkar-e-Taiba

- Published

Lashkar-e-Taiba is blamed for the 2008 attacks in Mumbai but has not admitted involvement

Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba (Soldiers of the Pure) is one of the most feared groups fighting against Indian control in Kashmir and is blamed for several deadly attacks on Indian soil.

Most high profile of these are the November 2008 attacks in Mumbai, external which killed 174 people, including nine gunmen, and soured ties between India and Pakistan.

Pakistan's former president, Pervez Musharraf, banned Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) in January 2002, along with four other Islamic groups. This followed considerable international pressure in the wake of the 11 September 2001 attacks in the US.

Until then LeT, with its reputation for being purely focused on fighting India in Kashmir, was able to operate openly inside Pakistan, raising funds and recruiting members.

Almost every shop in the main bazaar of every Pakistani town, large or small, had a Lashkar collection box to raise funds for the struggle in Kashmir.

Anti-US banner

LeT had no involvement in sectarian attacks in Pakistan and its leaders were often critical of other militant groups operating in Kashmir and Afghanistan who also took part in the sectarian Sunni-Shia bloodshed within Pakistan.

The scene at Chattrapati Shivaji Railway Station after the 2008 attack which killed a total of 174 people

Problems arose, however, when some breakaway LeT members began to disagree with President Musharraf's strategy - post 9/11 - and were blamed for anti-government attacks in Pakistan.

In the months after 9/11, these breakaway factions of militant groups started to come together under a loose anti-US banner.

This meant that LeT members came into contact with sectarian groups which it had previously so disdained.

After the ban, the government did not try to break up LeT but restricted the movements of its leaders, while its members were told to keep a low profile.

By mid-2002 it reportedly renamed itself Jama'at ud Dawa or JuD (Party of the Calling). It said it would continue its activities in Pakistani-administered Kashmir.

Hafiz Muhammad Saeed who founded LeT in the late 1980s, soon after the birth of its parent religious organisation, Markaz Dawa ul Irshad, now runs JuD.

JuD denies any links to the militant group. It called itself a charity in 2005 after a massive earthquake in the region and was allowed openly to collect funds in Pakistan, officially for reconstruction work. Many of their offices reopened and its members played a prominent role in rebuilding work.

But cables released by Wikileaks in December 2010, attributed to US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, said Mr Saeed and Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi, considered the head of LeT, "continue to run" LeT. This was "despite being detained for their role" in the Mumbai attacks.

The US put a $10m (£6.2m) bounty on the head of Mr Saeed in 2012.

War threat

Since LeT's rise to prominence more than 10 years ago, it has often been blamed by Delhi for carrying out armed attacks in Indian-administered Kashmir and India.

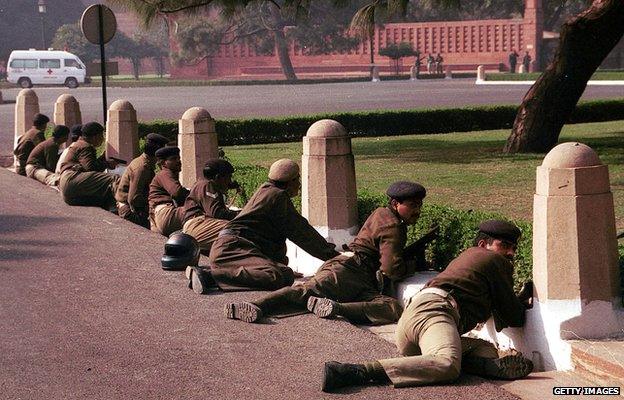

Delhi police commandos took cover after armed men stormed India's parliament in 2001

These included bomb attacks in Delhi in October 2005 that killed more than 60 people.

India also says LeT was involved in the most audacious attack on Indian soil in December 2001. The armed raid on India's parliament - allegedly carried out along with another Kashmiri militant group, Jaish-e-Mohammed - brought India and Pakistan to the brink of all-out war.

LeT has not admitted carrying out those attacks. But it does claim responsibility for attacking one of the country's most famous landmarks - the army barracks at the Red Fort in Delhi in 2000 in which three people died.

Until its ban in 2002, LeT had never been shy of accepting responsibility for most of the armed attacks against Indian military targets.

The US put a $10m (£6.2m) bounty on the head of LeT founder Hafiz Saeed in 2012

However, it always denied killing civilians, maintaining that such a tactic was against the organisation's religious beliefs.

In recent years, it has abstained from claiming responsibility for such attacks.

Hafiz Mohammad Saeed speaking to the BBC in January 2012

It did not claim responsibility for the November 2008 attacks in Mumbai, but a subsequent investigation by Pakistan found that its members had been involved in planning and carrying them out.

The Pakistani revelation came amid mounting international pressure to rein in groups attacking India with covert Pakistani support.

Many militant factions in Pakistan's north-west also consider LeT and some other Kashmir-focused groups such as Jaish-e-Mohammad, as the "lackeys" of Pakistan's security establishment.

Militant evolution

In the 1980s LeT's Markaz (Centre for Preaching) was set up in the town of Muridke, outside Lahore by a former professor of engineering at the University of Punjab, Hafiz Mohammed Saeed.

Spread over several hectares, the Markaz soon became known for preaching hardline views on Islam.

Some of its annual congregations attracted as many as 100,000 people, during which calls were made for jihad or holy war.

By 1994 LeT had emerged as the militant wing of the organisation.

Unlike most other Kashmir militant groups, a majority of its members were non-Kashmiri, and its headquarters were also based in Pakistan.

LeT generally shunned the alliance of the Kashmiri militant groups, preferring to act alone.

Initially it was ignored by most other groups, but earned their respect once it introduced the concept of "Fedayaeen fighters" to carry out daring attacks against the Indian troops.

The Mumbai attacks were a demonstration of this concept, leading many analysts to conclude that they bore LeT's signature.

- Published3 April 2012