Welcome to Cambodia: What Australia isn't telling refugees

- Published

A fact sheet for migrants portrays Cambodia as a country with no violent crime or stray dogs

Take a one-way ticket out of a Pacific island detention centre and you could start a new life in a country where you are told jobs are waiting, quality medical services are available, and there are no problems with violent crime or even stray dogs.

Free accommodation is provided, along with monthly income support, health insurance, complimentary language classes and more.

Sound a lot like Utopia?

Try Cambodia, one of the poorest countries in the world.

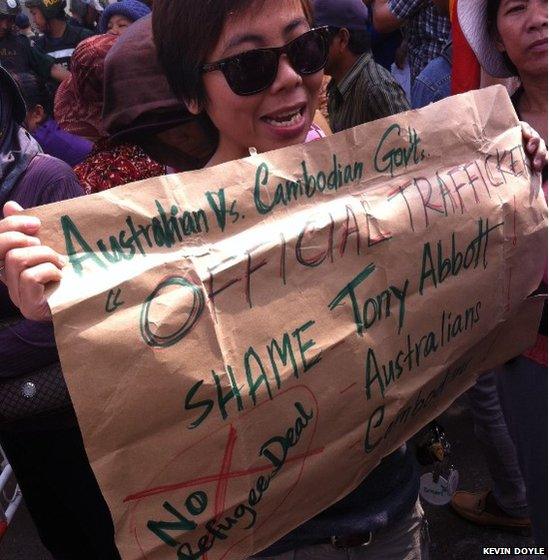

Re-settling migrants in Cambodia has proved controversial

Or, welcome to a version of life in Cambodia promised to four refugees - two Iranian men, an Iranian woman and a Rohingya man from Myanmar (also known as Burma) - for agreeing to resettle in Cambodia instead of Australia.

When they arrive in the capital Phnom Penh from Darwin, the four will be the vanguard of a controversial deal in which Cambodia has agreed to resettle Australia's unwanted refugees.

Hundreds of them are detained on the Pacific island of Nauru. In return for receiving those who volunteer to resettle, Cambodia has been promised A$40m ($31m; £20m) in aid money.

Refugee groups have attacked the deal, accusing Tony Abbott's government of abrogating Australia's responsibilities to refugees and paying off an impoverished Cambodia. Members of Cambodia's opposition party have accused Australia of using their country as a dumping ground.

The plan has also been ridiculed for providing a standard of living to refugees - initially at least - that many Cambodians could only dream of. Around 18% of Cambodia's 15 million people survive on less than $0.93 (£0.61) a day.

Initially, the four refugees will be housed in a villa in the south of Phnom Penh. They will receive income support, health insurance, classes in the local language, cultural and social orientation, and assistance in finding work or educational opportunities, said Leul Mekonnen, chief of mission of the International Organization for Migration in Cambodia.

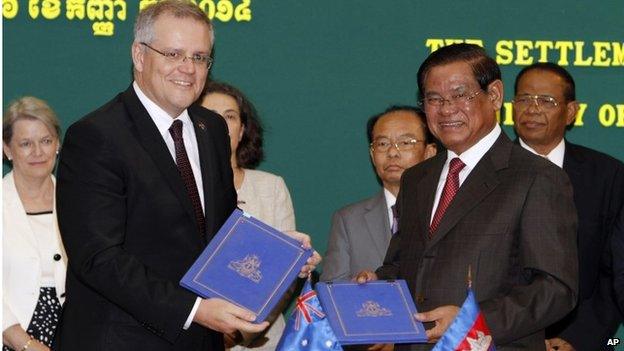

An agreement was signed between Cambodia and Australia last year

Due to intense scrutiny of the refugees' transfer and to ensure privacy, their identities are being kept confidential, as is the amount of financial support they receive, Mr Mekonnen said.

"There will be initial assistance which may be considered higher than local standards. But they need it," he added.

'So sad'

This has caused resentment among some in Cambodia which saw protests in 2014 when the re-settlement deal was agreed.

"I am amazed that refugees will be accommodated in villa-style houses and will have teachers coming to give them Khmer lessons and others, when our own Khmer population are kicked out from their own land and have to survive on their own," one Phnom Penh resident wrote in a Facebook post.

"Australia paid millions to resettle those refugees, compared to our population who have nothing to give in exchange… So sad."

The Australian government has paid the first Nauru migrant volunteers lump sums of up to A$15,000 ($11,500; £7,500), national media have reported.

More than A$15.5m ($12m; £7.8m) has been allocated to the refugee resettlement plan in Cambodia, on top of the A$40m ($31m; £20m) promised to the Cambodian government, the Australian Senate Committee has been told.

A "fact sheet" on life in Cambodia given out on Nauru, serves to act as an inducement.

It paints an implausibly rosy picture of life, describing the country as "rapidly developing" with "all the freedoms of a democratic society", as well as "a high standard of health care with multiple hospitals", and no "violent crime or stray dogs".

Australia's unwanted refugees are detained on the Pacific island of Nauru

What Australia tells its own citizens about Cambodia is rather different.

"Health and medical services in Cambodia are generally of a very poor quality and very limited in the services they can provide," Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs says on its website.

"Outside Phnom Penh there are almost no medical facilities equipped to deal with medical emergencies", while "hospitals and doctors generally require up-front payment in cash. In the event of a serious illness or accident, medical evacuation to a destination with the appropriate facilities would be necessary," the website warns.

And, crime is a concern: "The level of firearm ownership in Cambodia is high, and guns are sometimes used to resolve disputes," the department notes.

Kem Sarin, director of the Cambodian government's refugee office at the interior ministry, declined to comment on the veracity of the fact sheet, apart from one claim - that Cambodia has no stray dogs - for which he gave this opinion: "There are dogs in all countries."

The country's main employers are minimum-wage garment factories where hundreds of thousands of young women from rural areas toil for long hours for relatively little pay - around $50 (£33) a week.

'Rich is okay'

Breast-feeding her sick daughter on the street outside a children's hospital in Phnom Penh waiting to see a doctor, Moeun Srey Lin, 32, paints a picture of the kind of healthcare, education and work opportunities available for her and the 70% of the population who are farmers.

She spent two hours on a bus to get to the city from her village. Her eight-month-old daughter has been sick for three weeks with a persistent high fever, cough and runny nose. She went to local, private health clinics three times in the past three weeks, spending her meagre income on treatments that have not been effective.

Asked about life in Cambodia, Srey Lin says it is hard to find work and educational opportunities. Healthcare is, as you can see, not very good, she says.

"If we are a poor family, our kids don't get a good education. If we are rich, it is okay because our kids won't have to work to help the family."

Lucrative jobs, skilled doctors and good schools do exist in Cambodia. But they are only accessible to a tiny percentage of this country's population.

Staggering wealth evident in Cambodia in the last few years says more about widening inequality, and endemic corruption, than an abundance of opportunities, or a rising tide raising all boats.

Additional reporting by Phorn Bopha

- Published26 September 2014

- Published26 September 2014