US-China tensions rise over Beijing's 'Great Wall of Sand'

- Published

- comments

Vessels purported to be Chinese dredgers have been spotted in the South China Sea

You often hear politicians and strategic thinkers talk about establishing "facts on the ground" - the need to take account of what actually exists when framing policy.

Well in the South China Sea, the Chinese government is going one step further.

As defence ministers and strategic thinkers from across the Asia-Pacific region gather for the annual Shangri-La Dialogue, external in Singapore, China is not just creating facts on the ground, it is creating the very ground itself.

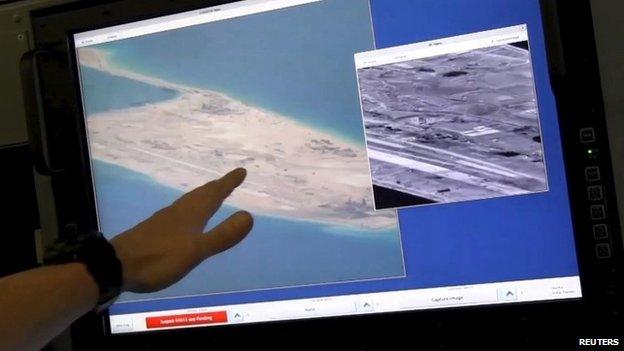

In a number of locations in the Spratly Islands, Chinese dredgers are spewing up torrents of sand from the sea bed, turning reefs into new islands.

The transformation of Mischief Reef for example, (known to the Chinese as Meiji Reef) in territory also claimed by the Philippines, is a case in point.

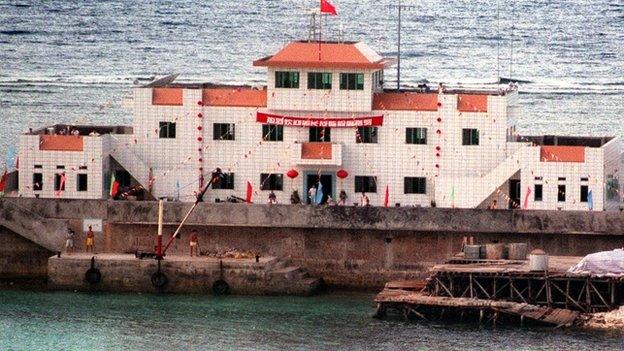

This is only one of several small outposts the Chinese have been constructing in an effort to press their expansive claims hundreds of miles from China's own shores.

The US says China has been building on reclaimed land in the disputed Spratly Islands

Every year the Shangri-La Dialogue, organised by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) brings together everyone who is anyone in Asia-Pacific defence circles "to take the temperature" - as IISS director general John Chipman puts it - of security developments in the region.

This year, once again, US-China tensions are centre stage.

Beijing's efforts to create new facts on the ground have been termed by some as an attempt to construct a "Great Wall of Sand" to delineate the boundary of China's interests - a reference to the ancient Great Wall that guarded China's frontier.

Mr Chipman says: "In both the State Department and the Pentagon, we are seeing real concern about Chinese activities in the South China Sea but also about some of the activities of other claimant states who have sometimes sought to make the areas they feel able to control more habitable or to build facilities on them."

'Preposterous' claims

So does he expect some strong exchanges over the coming few days on this subject?

After all, the newly promoted head of US Pacific Command Admiral Harry B Harris only a day ago described, external China's claims to a vast swathe of islands in the South China Sea as "preposterous".

Admiral Harris was speaking on his way to Singapore where he is accompanying his boss, the US Defence Secretary Ash Carter, who is also known for his habit of plain speaking.

"The US Secretary of Defence is going to err on the side of strategic clarity rather than strategic ambiguity," Mr Chipman told me, "and really call for a stop to this activity by all sides.

"After all in 2002, all of the Asean states, external in a declaration of principle agreed, external not to seek to change the status quo."

That's a polite way of saying expect tough words from the Americans.

The US and Philippine militaries conducted exercises in April near disputed islands in the South China Sea

But what about actions? US maritime patrol aircraft and warships have already ventured close to some of the newly constructed facilities, ignoring urgent messages from the Chinese authorities to go away.

There is a real danger of serious friction. "The US is going to argue that it needs to continually demonstrate the freedom of the seas," says Mr Chipman.

One of the things he hopes will happen at this Singapore meeting is that "there will be a continuation of the US-China military-to-military talks to try to ensure that there are no accidents or incidents at sea or in the air".

By Rupert Wingfield-Hayes

There are many competing claims to territory in the South China Sea, but only China and Taiwan claim to own it all.

Beijing's claim - not only to the Spratly Islands, but also the Scarborough Shoal and the Paracel Islands - is marked out on its own maps by the infamous "nine-dash line", which encompasses a huge tongue-shaped expanse stretching right up to the coasts of the Philippines and Vietnam and even Borneo.

The Philippines and Vietnam also claim large areas of the South China Sea. Both say most of the Spratly Islands belong to them.

For decades China has done little to enforce its vague and sweeping claim. Now that is changing.

In 2012 the Communist Party reclassified the South China Sea as a "core national interest", placing it alongside such sensitive issues as Taiwan and Tibet. It means China is prepared to fight to defend it.

Just ahead of the meeting, Beijing has published what many have dubbed a "Defence White Paper" setting out the country's strategic horizons and goals.

Mr Chipman believes that this document "will be seen in time as a foundational text for a new more extrovert Chinese defence policy.

"It actually says that China should abandon its obsession with land security and that security overall has to be achieved through predominance at sea. They are almost casting the Navy as the senior service."

'Responsible stakeholder'

Of course, he notes, there are two aspects to this document. In its concluding paragraph it says that China wants to contribute to the public good of international security.

It's a signal that Beijing is interested in playing a wider role - something senior US officials have long demanded of China, that it become "a responsible stakeholder" in international society.

China's activities have prompted occasional protests in the Philippines

Human security will also figure in the talks over the coming days, the plight of the Rohingya boat people highlighting the complex issues thrown up by refugees and migration.

In the Asia-Pacific though, just as in Europe, there are no easy answers here given the powerful mix of diplomatic and domestic factors.

The Shangri-La Dialogue derives much of its importance from the fact that there is no formal security architecture in the region - there's no Asian Nato for example.

While there have been meetings of Asean defence ministers, and wider gatherings, Mr Chipman told me that it is "very difficult to imagine" a formal defence body in the region.

Some countries, he says, "will tilt a bit towards China, some will tilt towards the United States, most would prefer not to have to have a choice and I think it is this that will still colour defence and diplomatic relations in the region for some time to come".

- Published26 May 2015

- Published8 May 2015

- Published3 May 2015

- Published7 July 2023

- Published15 October 2014

- Published9 September 2014