Asia's smartphone addiction

- Published

Nomophobia - or no mobile phone phobia - the onset of severe anxiety on losing access to your smartphone has been talked about for years. But in Asia, the birthplace of the selfie stick and the emoji, psychologists say smartphone addiction is fast on the rise and the addicts are getting younger.

A recent study surveyed almost 1,000 students in South Korea,, external where 72% of children own a smartphone by the age of 11 or 12 and spend on average 5.4 hours a day on them - as a result about 25% of children were considered addicted to smartphones. The study, to be published in 2016 found that stress was an important indicator of your likelihood to get addicted.

Smartphones are central to many societies but they have been integrated into Asian cultures in many ways: there is the obligatory "food porn" photograph at the beginning of any meal; in Japan it is an entire subculture with its own name - keitai culture.

Asia and its 2.5bn smartphone users , externalprovides a stream of phone-related "mishap news", such as the Taiwanese tourist who had to be rescued after she walked off a pier while checking Facebook on her phone. Or the woman from China's Sichuan province rescued by fire fighters after falling into a drain, external while looking at her phone.

They may make for slapstick headlines but in Singapore too the concern is that those most vulnerable are getting younger. With its population of just 6 million, it has one of the world's highest smartphone penetration rates. It also has specialists in digital addiction, a cyber wellness clinic and a campaign to see digital addiction be formally recognised.

"Youths lack that level of maturity, making it harder for them to manage smartphone usage as they don't have self-control," said Chong Ee-Jay, manager of Touch Cyber Wellness Centre, external in Singapore.

He has serious concerns about how young children behave when they get phones.

"They are readily available to very young children here as part of their school curriculum," he said. In Singapore it is not uncommon for homework assignments to be set via WhatsApp.

In South Korea, 19-year-old student Emma Yoon (not her real name) has been undergoing treatment for nomophobia, external since April 2013.

"My phone became my world. It became an extension of me.

"My heart would race and my palms grew sweaty if I thought I lost my phone. So I never went anywhere without it."

Ms Yoon's parents also said that their daughter's smartphone usage amplified other behavioural problems she was exhibiting. She began to retreat from hobbies and school activities.

Eat, shoot, post - Many smartphone users in Asia actively make use of Instagram to document their meals

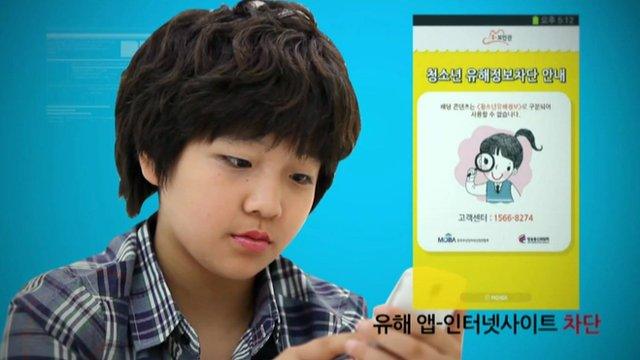

More young children regularly use smartphones around Asia

Many people will recognise the feeling of anxiety when the pocket feels strangely light but the difference here is that the phone becomes the focus of other problems and anxieties. The South Korean study also found that people who used their smartphones for social media purposes were more likely to get addicted.

The device is seen as the sole key to wider human contact. Vulnerable children and young adults can feel adrift and unable to connect to others without it. In some Asian societies, where students are set heavy and time-consuming homework tasks to complete on their own, the phone is the only connection to to friends, humour and sharing. So it can assume a disproportionate importance.

Here in Hong Kong - protesters hold up their smartphones to light up the night skies

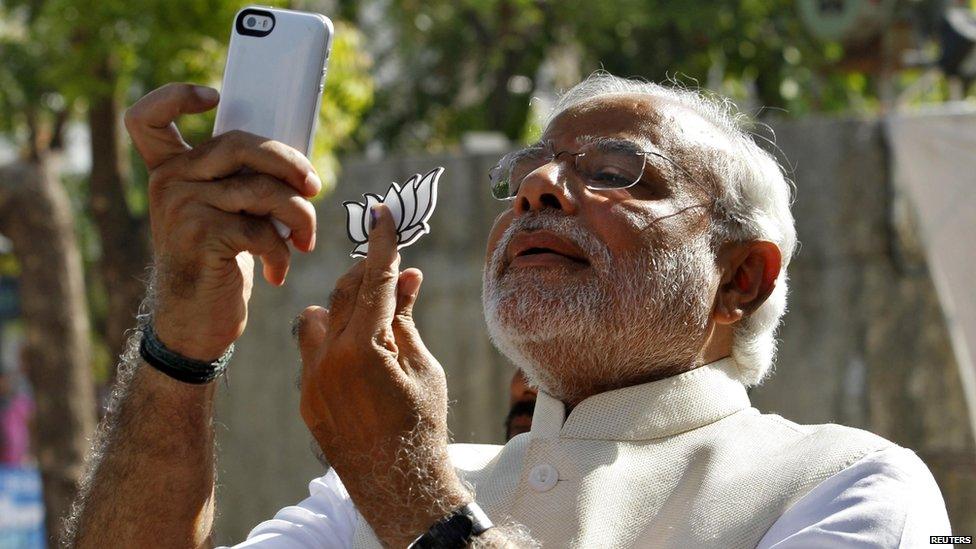

Selfie king? Political leaders like India's Narendra Modi have been reaching new audiences using social media and smartphones

Are you addicted to your smartphone? Experts say these are some early warning signs:

Constantly checking your phone for no reason

Feeling anxious or restless at the thought of being without your phone

Avoiding social interaction in favour of spending time on your phone

Waking up in the middle of the night to check your smartphone

A decline in academic or work performance as a result of prolonged phone activity

Easily distracted by emails or smart apps

Experts told the BBC that younger smartphone users lacked the "maturity" needed in curbing everyday usage

Several countries have started imposing regulations on smartphone usage.

A controversial government app to monitor smartphone usage among teenagers sparked heated debate in South Korea. Officials also imposed a series of measures in 2011 banning children from accessing online games after midnight.

China, one of the first countries to label internet addictions as clinical disorders, set up military-style clinics, external to stamp out new media addictions.

Consultant psychiatrist Thomas Lee argues that other countries in Asia should follow suit and classify smartphone addictions as "official mental disorders" in the way sex and gambling have been designated.

"Using a smartphone to benefit one's mood is almost similar to how drugs are able to affect a person's behaviour," said Mr Lee.

"Like drug addicts, smartphone addicts will also display withdrawal symptoms like restlessness, anxiety and even anger."

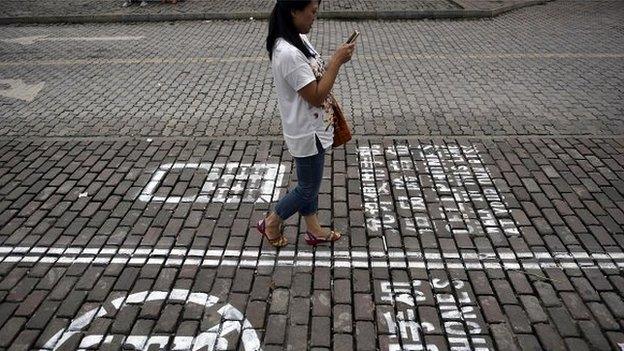

Watch your step - This smartphone sidewalk appeared in the Chinese city of Chongqing

But there is a strong counter-argument that this is all overblown and simply part of modern society's tendency to overthink itself. Singapore-based Clinical psychologist Professor Marlene Lee says technology disorders are not a new phenomenon.

"Research is still preliminary so there are still many unanswered questions at this point. Technology addictions actually share the same underlying mechanisms as other addictions; they just have new 'faces'," she said.

Her argument has support from psychiatrist Adrian Wang who says he is reluctant to diagnose such addictions to avoid "medicalising social problems, as they are simply "part of larger social problems like family and self-esteem issues".

There will doubtless be another smartphone-related innovation born in Asia, which will catch on just like the selfie stick, the animated avatar and the emoji. Psychologists across this vast and varied continent hope that what will be shared is something positive and creative and not just anxiety.

- Published15 June 2015

- Published18 November 2014

- Published15 September 2014

- Published14 July 2014