The Dhaka slum being transformed by women

- Published

The hanging toilets provided extremely rudimentary facilities

In the centre of Dhaka, a few streets away from high rise office blocks and the penthouses of the wealthy, lies the city's biggest slum.

It stands on a patch of land that was once a barren field, but started to be settled at the end of the 1970s, mostly by people who came to Dhaka in search of work and had nowhere to live.

Today, Korail, external is estimated to have 200,000 residents, many of them living in small shacks with bamboo frames and corrugated tin roofs.

As I walked in, my first impressions were as you might expect - dominated by the dirt and the numbers of people living in crowded conditions.

But as I walked a little further, a different perception of life in Korail started to take hold.

Many of the paths had been concreted, there was a mosque and a school built of brick, health workers going from house to house in their white coats, and shops and stalls serving the local residents.

Some of these improvements are due to a development experiment that has been undertaken in Korail, putting the decision-making power into the hands of the people who live here.

Big role for women

The Urban Partnership for Poverty Reduction, external began in Korail in 2010, with funding from the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and British overseas aid.

Every 20 households banded together to form a "primary group" of stakeholders, with elected representatives of each of these groups forming community development communities.

Women in the slum are delighted with the new toilets

These, in turn, elect members to the top layer, known as clusters, which are then a point of contact for outside development assistance.

Kazi Morshed, of the UNDP, explained to me how the system came up with ideas from the residents that his organisation had not envisaged - for example a creche so that the women of Korail could go out and work.

The clusters, which are asked to identify the priorities for improvement, are dominated by women.

Sumona, 23, who chairs one of them told me: "I used to be confined to my house, ignorant of what was happening around me. Now that I am in a leadership position, my husband has started listening to me, and the neighbourhood also looks to me for solutions to its problems."

Korail is the biggest slum in Dhaka

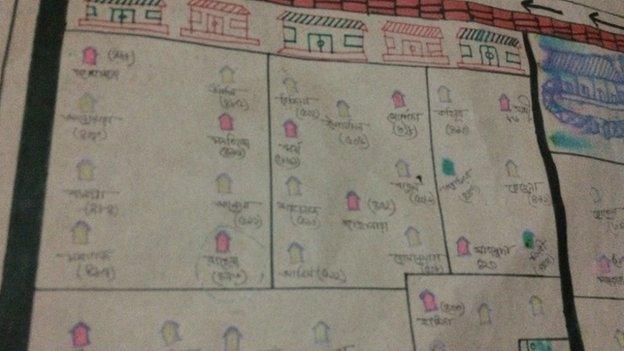

On the wall next to her was a hand-drawn map of Korail's households, divided into sectors, with those in most need marked in red.

Next to it was the neighbourhood's action plan - a record of the priorities identified, and who was responsible for delivering them.

In this way, the people of Korail have asked for - and built - footpaths and drains, and negotiated with the local authority for water supplies.

But they are probably proudest of their new latrines and the transformation of a muddy piece of land used for open defecation into a block of six toilets.

It was their idea to assign each toilet to a group of 10 families, who are then responsible for keeping it clean.

Health benefits

Minara, another of the elected Korail women, told me there was an immediate health benefit from the toilets.

She said: "We used to get a lot of infections from the water-borne diseases, but now it's almost zero.

"We used to have to take the children to the hospital every week and spend a lot of money on medicines. Now we can save that, or spend it on food."

Action plan, highlighting the households most in need in red

As I looked at the signs on the doors of the toilets - UK Aid - from the British people - I wondered how many UK taxpayers would appreciate all the different ways in which these simple toilets were life-changing in Korail, not just for health, but human dignity.

Minara smiled broadly as she told me: "I would like to thank the people who paid for this. They have given us a better life."

Korail has benefitted from the Urban Partnership for Poverty Reduction

Beyond physical improvements to the slum, the clusters also have a role in identifying those among them who would benefit from loans or grants, or help with new skills so they can get a job.

And the empowerment goes beyond the women's contact with aid agencies and NGOs.

Shoma told me that her position representing the community has given her the courage to go to the police with a complaint about a pair of neighbourhood thugs.

In the past, contact with the police would have been avoided by anyone living in Korail, particularly the women.

Changed lives

Kazi Morshed of the UNDP has no doubt that the experiment has been a success, and hopes that it can be replicated beyond Bangladesh.

"The results have changed lives and livelihoods, income levels have gone up, people have savings and hope for tomorrow."

Beauty is able to access good antenatal care

Further down the street, I could see evidence of the same organisation and identification of need at a maternity centre run by Brac, Bangladesh's dominant NGO.

The mission of its doctors was to reduce the numbers of home births in Korail, which in 2007 amounted to 86% of all deliveries.

The approach is house to house - a woman from the neighbourhood is given basic training and asked to identify any pregnant women.

When one is found, a poster is stuck up in her home with the telephone number of the maternity centre, and community health workers are sent in for her ante-natal check-ups.

I followed the team as they went to see a young woman called Beauty, seven months pregnant with her second child.

Her blood pressure was taken, and advice given on nutrition and rest, with everything recorded in a notebook kept by the patient as a complete history of her pregnancy.

Urban Partnerships for Poverty Reduction Project in Bangladesh:

More than 800,000 households have joined roughly 2,500 community development committees, mostly led by women.

166,000 households are now accessing improved water sources while 143,000 households have new toilets. Over 90% of households report being satisfied with these improvements.

More than 88,000 extremely poor women have been supported to set up their own businesses through small enterprise grants.

376,000 households now participate in savings and credit groups with more than $5m of savings and $3.7m worth of loans at the end of 2012.

Today, home births in Korail are down to 11% of deliveries, and Bangladesh is on track to meet the Millennium Development Goal on maternal mortality.

In spite of all these improvements, Korail is still a tough place to live.

On the other side of the slum I saw the old style "hanging toilets", where people defecate straight into the lake, with the sky line of rich Dhaka a stone's throw away.

But from the women who had managed to bring improvements to their part of Korail, I saw an admirable confidence - a belief in their own ability not just to pinpoint what their community requires, but also to find solutions.

They now know that their voices matter, and from that, there's no going back.