Mystery surrounds India health survey

- Published

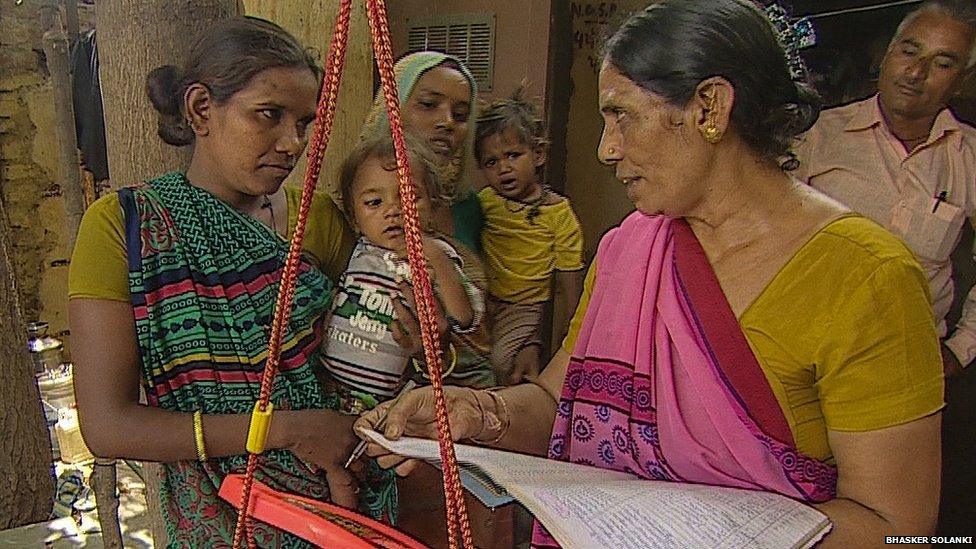

About a third of India's children are underweight, the survey says

Good health data is rare in India. The last time the country published a comprehensive, state-wide survey was back in 2007.

So why hasn't a vast survey of women and children carried out by the Indian government with the UN agency for children, Unicef, been released?

India's so-called Rapid Survey of Children was a huge undertaking. Almost 100,000 children were measured and weighed and more than 200,000 people interviewed across the country's 29 states.

The final report was due for publication in October last year, the BBC understands. Yet, more than half a year later, the important body of data remains secret.

Leading development economist Jean Dreze describes the delay in publication as "an absolute scandal".

"All the neighbouring countries including Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Pakistan and even Afghanistan have up to date nutritional surveys," he says.

"It is hard to account for a 10-year gap without attributing some sort of political reluctance."

Fatima Bano, who is nearly three, is so weak she still has to be carried by her mother

Unicef says it understands that the government is "reviewing the survey methodology" - but the agency is looking forward to the release of the data.

"Data is crucial for making sound evidence-based plans," explains Saba Mebrahtu, Unicef's head of nutrition in India. "It helps us understand what is causing under-nutrition so that interventions can be focused in those areas."

Poor performance

The BBC has asked the Indian government why it hasn't been released and when it expects to - but we haven't received a response.

We have, however, managed to get hold of a copy of the report.

Looking just at the overall figures, India's reluctance to publish the survey is rather surprising.

It shows the country has an encouraging story to tell. Indicators of malnutrition are still very high, far higher than most African nations, but they are improving.

Ten years ago, two-fifths of children under five were underweight, now it is more like a third.

However, the survey confirms large and enduring discrepancies between states, including the continuing strikingly poor performance of the Indian prime minister's home state, Gujarat.

As chief minister, Narendra Modi ran the state for more than a decade. His general election campaign was based on the promise that he would do for India what he had done for Gujarat.

Narendra Modi ran Gujarat for more than a decade

The results of the survey might lead some people to question whether - in terms of health - it is really a model the nation should seek to emulate.

It shows that despite impressive economic growth, the state continues to have some of the worst health outcomes in India.

It says 41.8% of children in Gujarat are stunted while 43.8% don't have the all the vaccinations they need, for example.

'Encouraging trends'

Gujarat's poor results have led to speculation that one reason the government has been holding back the report is to spare the prime minister embarrassment.

It certainly appears that Gujarat's shortcomings are, at least in part, a result of policy.

These three 25-year-old mothers, born in Ahmedabad, are illiterate and their children are all malnourished

A decade ago a survey found the neighbouring state of Maharashtra had malnutrition figures almost as woeful as Gujarat does now.

Maharashtra decided to take action. Sujata Saunik, the head of the state's health department, says it used the data from that earlier survey to design a programme to improve child health.

It has been a great success. She says stunting has been cut by almost 41% and in the number of underweight babies is down by 24%.

"These are encouraging trends," she says, rather modestly.

India, however, is unlikely to see similarly dramatic changes in the national picture.

The Indian government spends just 1% of GDP on healthcare - one of the lowest figures in the world.

And since Mr Modi came to power, he has cut central government spending back.

- Published11 August 2012

- Published10 January 2012

- Published21 December 2011