The last Catholic priest in the Antarctic

- Published

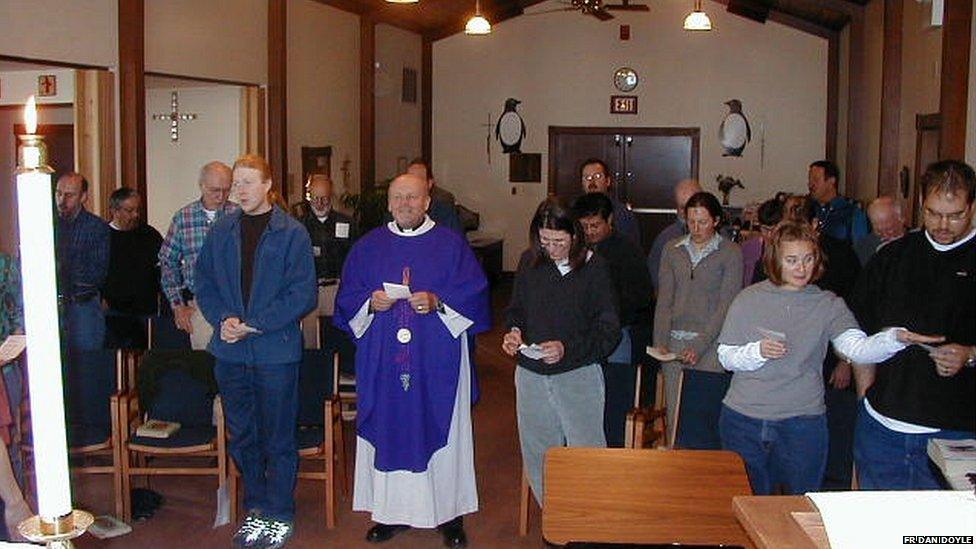

Father Dan Doyle said he was "just an ordinary fellow" when he took up the job to serve the Chapel of the Snows

Every southern summer for the past 57 years, Catholic priests from New Zealand have packed their warmest clothes and travelled some 4,000km (2,500 miles) south, to the frozen wastelands of the Antarctic.

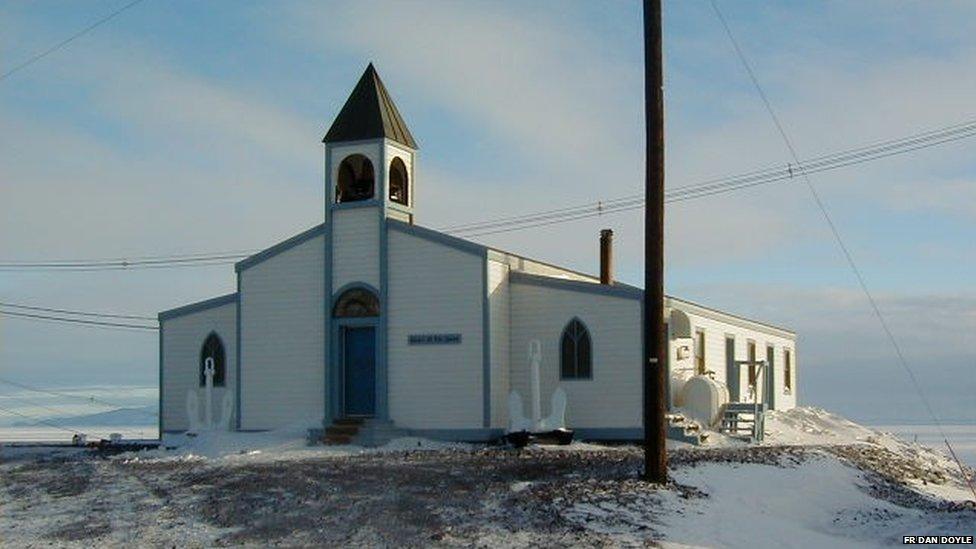

New Zealand's Catholic Church, external has had an annual invitation from the US National Science Foundation to spend their summer months at the Chapel of the Snows at the remote US McMurdo Station on Ross Island, serving the spiritual needs of the scientists and researchers based there.

But a combination of cost-cutting and a fall in demand means that, this year, the Americans have decided the last Kiwi priest has said Mass on the ice.

"We're really sad," says one of those priests, Father Dan Doyle, from his home in Christchurch.

"After 60 years of ministry at the end of the Earth - a great challenge in an amazing place - to be told that we're not needed anymore... it's a bit sad."

The chapel is the southernmost place of worship in the world

Father Doyle has been the leader of New Zealand's Antarctic Ministry for the past 15 years, spending 14 summers at the base as priest to a maximum summertime population of 2,000.

In the winter, when the Antarctic falls dark, the population drops to about 150 essential staff.

He was "just an ordinary fellow" when he took up the challenge, he says, but it was "a joy to be involved".

Each day there was varied, he says, as he worked alongside his Protestant counterparts.

"When I'm on the ice, we have a church service every day. On Sundays we get big numbers, on weekdays a small number."

Even the Amundsen-Scott base at the South Pole had a regular visit from the priests

The priests also went out to the work places, office and labs, offering support and encouragement, and checking on people's wellbeing.

They would often receive calls from people worried about their workmates, so "we'll occasion on them and ask how things are going".

Life so far from home can be hard, especially for those involved in stressful work in tough living conditions.

"People get very isolated," he says. "Thirty years ago, when I was first there, we didn't have all the wonderful digital communications we do now.

"We could get a two-minute ham radio call once a month. Nowadays there's Skype and email, and great internet and telephone communications, so it's much less stressful."

Once every couple of weeks, they would even travel to the South Pole - a 1,360km (845 miles) journey - to conduct religious services or Mass at the Amundsen-Scott Base, the southernmost inhabited place on Earth.

Making contact with home was much harder in the early days of Antarctic residences

As for the "hatches, matches and despatches" which are the bread and butter of a more routine priestly life, while it's not possible to get legally married in the Antarctic - as it's not claimed by any one country - people have held symbolic ceremonies, he says.

Equally, while no-one can legally be buried in the Antarctic, he has performed last rites and conducted memorials for those who've died far from home.

And there are no children in Antarctica - under 16s are not allowed to be there. But Father Doyle has performed baptisms of adults, who perhaps found that their time in the snowy south stirred some sense of the divine.

Kiwi priests on the Antarctic tundra

The first New Zealand priest to travel to Antarctic was Father Ronald O'Gorman from Christchurch, who went out on a US Navy icebreaker in November 1957 to assist the Navy chaplain, says the Christchurch Antarctic Mission., external

Two subsequent priests made a permanent impression on the region, having geological features named after them.

Coleman Peak, external, a 1,600m mountain on Ross Island, was named in 2000 after New Zealand priest Father John Coleman, who served 20 years at McMurdo, and died in 2003.

The four-mile-long Creagh Glacier, external in Victoria Land was named after Father Gerry Creagh in 1995. He was the unofficial US Navy chaplain at McMurdo base for more than 25 summers, earning himself the title "Chaplain of Antarctica".

'A wonderful adventure'

The National Science Foundation said the New Zealand priests were a valued part of the community, but a decline in churchgoing numbers meant this particular programme was no longer viable.

"There are Catholic chaplains available through the US military, so it's not as if practising Catholics will not be able to avail themselves of services and a Catholic priest," spokesman Peter West told the BBC.

As priest, Father Doyle not only celebrated Mass but also supported people struggling with being so far from home

"But this particular programme we cannot accommodate any longer," he said, adding that Father Doyle and the New Zealand Catholic Church were consulted throughout.

A protestant priest will still take a stint each summer at McMurdo, providing interdenominational services - so the base won't be left a godless wasteland. Russia also has a priest installed in a church at its base on King George Islands, on the other side of the continent, and there are a handful of churches dotted around.

But Father Doyle says he accepts that he and his New Zealand colleagues were guests of the US, and that, with the ease of communicating with home and a general fall in numbers at the base, "there's just not the demand that there was 30 years ago".

But for him, it marks the end of a "wonderful adventure".

"Going onto the ice and listening to the wind whistling around the icebergs, seeing the beautiful wind-sculpted ice," he says of his favourite memories.

"Going in to the face of glaciers and crawling around the tunnels, seeing all the beautiful colours. The glaciers sing when you tap them you know, because the ice is under stress, so it rings like a bell.

"You think white is one colour, but white is a thousand colours when you get inside a glacier and it's all around you."