MH370 search: Does debris solve the mystery?

- Published

The barnacles on the plane part are commonly found on flotsam in the Indian Ocean

Malaysian authorities have said an aeroplane part found on the island of Reunion in the Indian Ocean did come from missing Malaysia Airlines flight MH370.

International investigators were more cautious, however, saying only there were "very strong" indications this was the case.

The plane disappeared between Kuala Lumpur and Beijing in March 2014 with 239 people on board - this is the first trace of it found.

What are the chances this find will solve one of the biggest aviation mysteries ever?

What does this mean for the search?

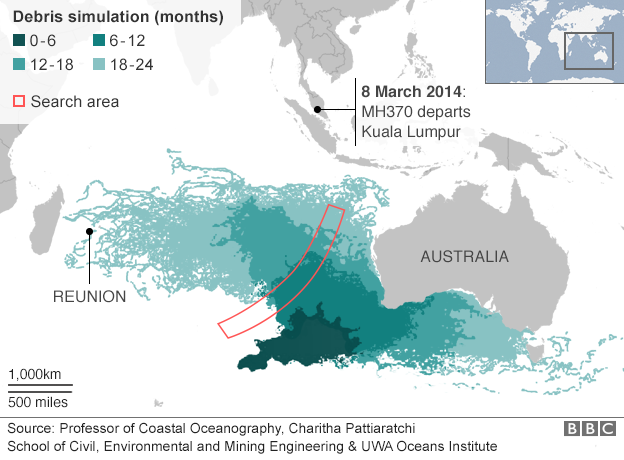

It appears to bolster the theory that the plane crashed into a patch of the Indian Ocean west of Australia after it diverted from its route.

Australian authorities including Prime Minister Tony Abbott said that the search would continue in the 60,000-sq-km area near Perth.

"It is heartening that the discovery of the flaperon is consistent with our search area and we will continue to search this area thoroughly in the expectation we will find the missing aircraft," said the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, which is leading the operation.

Reunion is roughly 6,000km (3,700 miles) west of the search area.

Australia's national science agency CSIRO has computer simulations of the debris path showing the pieces would have initially stayed at the latitude of the search site, before winds and currents - known as the Indian Ocean gyre - pushed them in a north-west arc.

The coloured dots in this animation from Australian national science agency CSIRO simulate items blown by wind, ocean currents and waves

On where the debris could have ended up, CSIRO oceanographer David Griffin says: "Madagascar was probably the highest probability, and Reunion is not far from that in the scheme of things."

Others have noted that a boat lost off the Western Australian coast last year was found nearly intact eight months later, west of Madagascar.

The plane part was found on a beach at St Andre, in north-east Reunion

How certain are investigators that the piece is from MH370?

Investigators have been examining the 2m-long (6ft) piece in Toulouse, France this week after it was found on a beach in Reunion on 29 July.

They have based their belief that the plane part could very possibly be from MH370 on two sources.

One is Boeing which has confirmed that the piece, called a flaperon, belongs to a 777 plane - the same model as MH370.

The other is Malaysia Airlines which has provided documentation on MH370's aircraft.

But investigators have stopped short of providing full confirmation, saying they can only do this after further tests on the fragment.

French prosecutor Serge Mackowiak, who has presented investigators' is exercising supreme legal caution, says the BBC's Hugh Schofield in Paris.

It could also be months before they make any tentative deductions about how the plane may have come down.

One key question is whether the plane part's serial number is intact, which French investigators have not mentioned.

Aeroplane parts, including flaperons, usually come with details such as a serial number, its manufacturer, and safety certification. These can be traced back to the manufacturer, who in turn would check its database to see which plane the part was used in.

Investigators say that Boeing identified the part based only on "technical characteristics" such as the colour and the structure of its joints.

The BBC's Richard Westcott explains how debris could have made its way to Reunion

Could it have been from any other plane?

There is no shortage of aircraft debris floating in the oceans so French investigators need to be absolutely certain this flaperon is not from another plane.

Several aeroplanes have crashed in the Indian Ocean or in the vicinity of Reunion in the past two decades, although none were Boeing 777s.

Two crashes involved large aircraft which ended up in waters near the Comoros Islands. One is Yemenia Airways IY626 - an Airbus 310 - which crashed in 2009.

The other is Ethopian Airlines ET961, external - a Boeing 767 - that crashed in 1996.

The Yemenia Airways crash in 2009 prompted a search for survivors by US, French, Yemeni and Comorean authorities

Could it help us find out what happened to MH370?

Greg Waldron, of Flightglobal, said what is really needed are the plane's flight recorders - one piece alone won't solve the mystery, he told the BBC.

Others say it is difficult to use the piece to pinpoint the exact location of where the plane is. "You can't trace the flight path with enough certainty based on this," said David Griffin from CSIRO.

Marine salvage expert David Mearns agreed with this assessment. He told the BBC that even if the debris was from MH370, the "uncertainty is too great" to find the crash site given that the plane disappeared 16 months ago.

"I have backtracked wreckage to locate shipwrecks but only over a drift period of one to three days," he said.

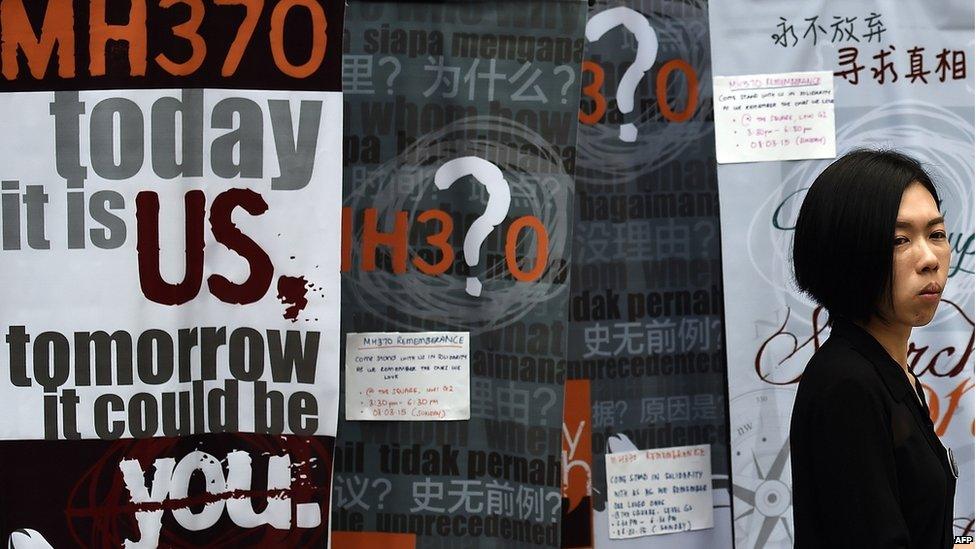

Questions remain about what happened to MH370 with searchers still unable to find any trace of the aircraft

How long had the flaperon been in the sea?

Police inspect the debris washed up on the island of Reunion

Robin Beaman, a marine geologist with Australia's James Cook University, said the pictures showed substantial marine growth - gooseneck or stalked barnacles - on the debris. These are commonly found on flotsam in the Indian Ocean, he told the BBC, and only on objects floating on the surface.

Mr Beaman said it was obvious from the barnacle growth that the part had been drifting for "quite a long time".

But he said it was hard to say how long exactly - it could be years or months - and that it was also unclear how long the part had been onshore before it was found.

The discovery of the plane part on 29 July has caused great excitement in Reunion

What do the families say?

The BBC's Jonathan Head speaks to Jacquita Gonzales, whose husband Patrick was an in-flight supervisor on flight

The announcement has been met with mixed reactions by relatives.

Sarah Bajc whose partner Philip Wood was on MH370, told the BBC: "Perhaps families will finally have the chance to grieve now, though this doesn't solve the mystery or hold anyone accountable. Both of those things still have to happen."

She added that there was still "much outstanding mistrust" of the authorities. "It hurts to have to give up that last thread of hope, but there is also a sad relief," she said.

Some say the finding does not necessarily mean the plane crashed into the sea.

Lee Khim Fatt, whose wife Foong Wai Yueng was on MH370, told the BBC: "I'm not convinced by the finding. I want to see an item that I can recognise.

Others have been angered by the difference in Malaysian authorities and French investigators' responses.