The Burmese Indians who never went home

- Published

Burmese Tamils speak to the BBC's Anbarasan Ethirajan

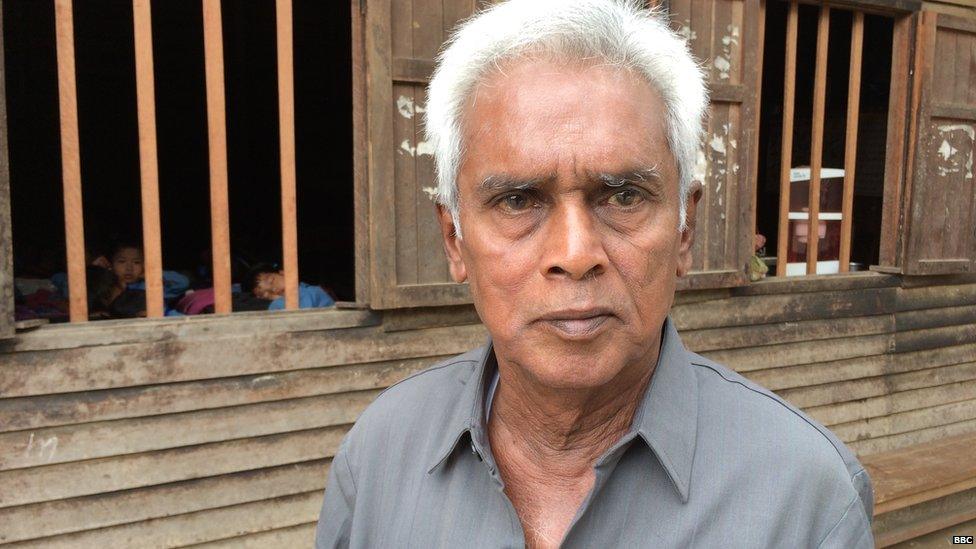

Every day Mohamed Eusoof Sarlan looks at his beloved homeland, a few hundred metres away from where he lives - but Myanmar's soldiers will not allow him to return to his country.

He is among thousands of Burmese Tamils living in the north-eastern Indian town of Moreh in Manipur state, which borders Myanmar, also known as Burma.

Mr Sarlan and other Indian-origin people were forced to leave the country following a military coup in the 1960s. Their businesses were nationalised and Mr Sarlan, who used to live in Rangoon (now called Yangon), and others became penniless refugees overnight.

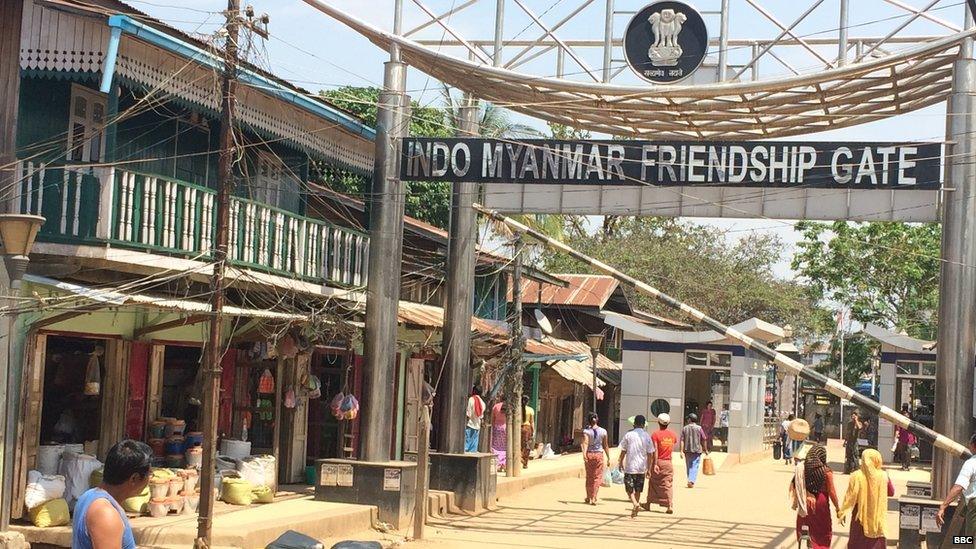

The border crossing in Moreh

Mr Sarlan has spent most of his life as a refugee

It is estimated that nearly 300,000 Indians fled the country following the coup.

"After we reached India, for the first three months we were living in a refugee camp in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. Though Tamil Nadu was the land of our forefathers, it was difficult to live there without any support," recalls Mr Sarlan, 74, who is now a social activist.

'Mini-India'

Indians lived in Burma for centuries, but large-scale migration took place during British-colonial rule, when the country was part of British India, during the 19th and early 20th centuries. They were used as civil servants, traders, farmers, labourers and artisans - and came to be considered the backbone of the economy.

Burmese nationalists always viewed them with suspicion and there were a series of anti-Indian riots in the 1930s. Once the British left in 1948, Indian-origin people became increasingly vulnerable and they were swiftly forced to leave following the 1962 coup.

They found it difficult to settle in India, so many decided to return to Burma by land. They vaguely knew that India's north-eastern states of Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh shared a border with Burma.

After weeks of travelling by train and bus a small group managed to reach Moreh, around 3,200km (2,000 miles) by road from Tamil Nadu. When they reached the border crossing, Burmese soldiers prevented them from entering the country.

The Tamils settled in Moreh hoping one day to return to their homeland - but those dreams have never been fulfilled.

Burmese Tamils have lived in India's north-east for half a century

People came to buy Indian goods in markets near the border

"Moreh was a tribal village when we first came here. There was hardly any infrastructure at that point. But many Burmese people came to Moreh looking for Indian goods like automobile parts, clothing and cosmetics. Since we knew the Burmese language it was easy for us to start businesses," Mr Sarlan recalls.

Soon, the Tamils in Moreh invited their relatives and friends from camps in Tamil Nadu and elsewhere to join them.

Many went on to become Indian citizens.

By the 1990s the number of Burmese Tamils in Moreh had increased to about 15,000, almost half of the town's population. They had set up their own schools, temples, churches and mosques - and celebrated their cultural festivals with fervour. Moreh was described as a "mini-India".

"We still retain lots of cultural and social links with Tamil Nadu state. For our important temple festivals we bring priests and music performers from there. Many parents in Moreh also send their children to schools in Tamil Nadu," says K Balasubramaniam, who is the principal of a local secondary school.

Chinese goods

At one point, Burmese Tamils dominated local border trade and that led to resentment from the Kuki community and others.

Several people were killed in bloody clashes between Tamils and Kukis in 1995, but relations have improved since then.

"We take part in each other's cultural and religious festivals. We have several committees to look into any problems and they get sorted out immediately," says Manohar Mohan, a Tamil businessman.

Tamil businesses suffered a setback after the Burmese government established a market just inside their border in Namphalong in the mid-1990s. Chinese products flooded in and many Burmese started shopping in Namphalong rather than Moreh.

Markets in Myanmar are now flooded with Chinese goods

Traders in Manipur also faced threats from insurgents in the state - some of the businessmen who refused to pay "extortion money" were shot dead.

The violence and lack of business opportunities forced many traders and Burmese Indians to leave Moreh, many opting for Chennai. Now Moreh's Tamil population is just 3,500.

'Gateway'

The insurgency has been contained to a large extent in the last few years. Many traders in Moreh hope the town will regain its business importance once the long-pending Asian Highway, linking the state capital Imphal with Yangon and Bangkok materialises.

Moreh is considered to be India's gateway to South East Asia and locals believe because of its unique geography the place offers tremendous potential.

Moreh is seen as India's gateway to Myanmar and Thailand

University student B Revathy says people are moving elsewhere to seek job opportunities

The story of the town's Burmese Tamils is one of suffering and resilience as well as achievement.

Many elderly Tamils, originally from Burma, are nostalgic and want to stay in Moreh, as it is closer to where they come from. But later generations say the town offers little in terms of education and employment.

"If we don't have the right education facilities then we have to go elsewhere. We can't do higher studies here. Also, girls can get only teaching jobs here in Moreh. So there are no other options but to leave this town and go to a place like Chennai," says B Revathy, a university student.

Emotional attachment it seems may not be enough for Moreh to keep its Burmese Tamils.

- Published13 August 2015

- Published4 April 2013

- Published26 May 2023