Migrant crisis: Afghan people smuggler talks frankly

- Published

People smuggler "Abdul": "What I am doing is not good. But when people ask me to help them, I think I'm doing a good job"

It is hard to know who is winning in Afghanistan.

The government is under immense pressure. Its underpaid and overstretched forces have been on the back foot in their first season without Nato combat support.

They are trying to push the Taliban back, most recently in the key southern province of Helmand - but the way the insurgents took the northern city of Kunduz still weighs on people's minds.

Afghans are watching all this with great concern. It is no surprise that - after Syria - the highest number of migrants in Europe come from Afghanistan.

People here wonder which is the greater gamble - continuing to live in Afghanistan or risking death on the journey out.

Trafficking boom

In the current climate one group is doing good business: people smugglers. The BBC gained rare access to one - we will call him Abdul (not his real name).

Abdul said a trip out of Afghanistan into Iran, Turkey and ultimately Europe costs between $5,000 and $7,000 (£3,250 to £4,550).

Afghans account for the second biggest number of migrants crossing into Greece

Many Afghan migrants face difficult conditions in Europe

Abdul gets 10%, the rest goes to other smugglers in the network and pays for transportation. Migrants pay a deposit and their families pay the balance when they reach their destination.

The journey is fraught with danger, something Abdul said he did not hide.

"The most dangerous part is between Turkey and Greece. People get shot by police and sometimes the boats capsize. But Allah guarantees safety, not me," he said.

People from all walks of life and various parts of the country seek him out, he said, but he will not take them if they are unhealthy, too old, with small children or pregnant.

Harun Najafizada asks why Afghans are leaving their country for Europe

Abdul seems conflicted about what he does - he feels he is helping people, but also acknowledges he is taking their money and sending them to an uncertain fate.

"I smuggled my own three sons. I miss them a lot and I get upset when I see parents crying. I don't like my job very much you know. I feel guilty sometimes," he said.

'Rather die'

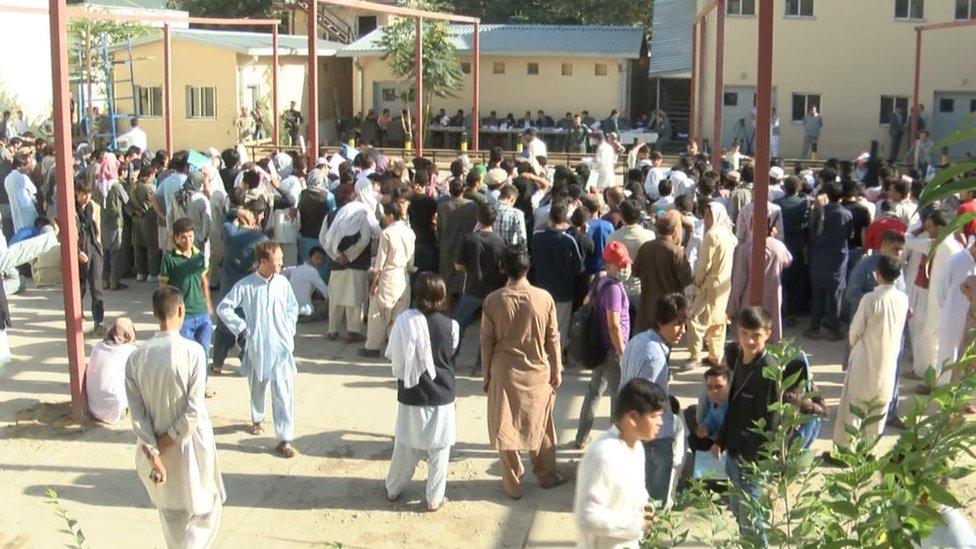

Standing outside the passport office on a chilly Kabul morning, it is easy to see why people like Abdul are in business.

Queues have already started forming. People crouch on car bonnets filling in forms. Everyone wants to leave - and most don't want to come back.

Arif Mohamady, in his late 20s, is angry and frustrated.

This passport office has been doing brisk business

Most Afghans want to leave - and don't want to come back

"There are no jobs here, no security and lots of corruption. I'd rather live in an infidel country," he said.

"In 2007 my father was killed in a suicide bombing. My mother and brother were killed by the Taliban. I know it's a dangerous journey but I'd rather die on the way than stay in Afghanistan."

'Afghanistan needs you'

Despite the overwhelming sense of despair, some take a more hopeful view.

A group of young people have started a digital campaign called "Afghanistan Needs You".

Shakib Mohsanyar, 23, said they wanted to stop the brain drain, while Sharam Gulzad, 26, said many Afghans had unrealistic expectations about life abroad.

"I was in Germany and I saw Afghans begging for the first time there. It was heartbreaking. People think once they arrive things will get better. They won't," he said.

Both acknowledged that the problems of corruption, lack of jobs and insecurity are all too real.

"When you go out in the morning you don't know if you're coming back home in the evening," said Mr Gulzad.

"But this is the risk we take. We do have potential. This is not the end of Afghanistan. If we take responsibility and action we will change this country."