The man who would be the first climate change refugee

- Published

Ioane Teitiota says his family's lives are in danger in Kiribati

With waves breaking at his feet, Ioane Teitiota holds his hand more than a metre above his sea wall to demonstrate how high the water gets during a king tide.

The wall seems hopelessly inadequate even when it's not full of holes. When he returned to Kiribati from New Zealand, he had to fix it in three places. And he expects to trudge out after almost every high tide to patch it up again.

The threat of sea-level rise was the basis of his four year battle to become the world's first recognised climate refugee.

But courts in New Zealand rejected his claim, and he was deported in September for overstaying his visa. He says that decision has put him in danger.

"I'm the same as people who are fleeing war. Those who are afraid of dying, it's the same as me," he says.

Like many in Kiribati, he's worried the ocean will swallow the entire country like some latter day Atlantis.

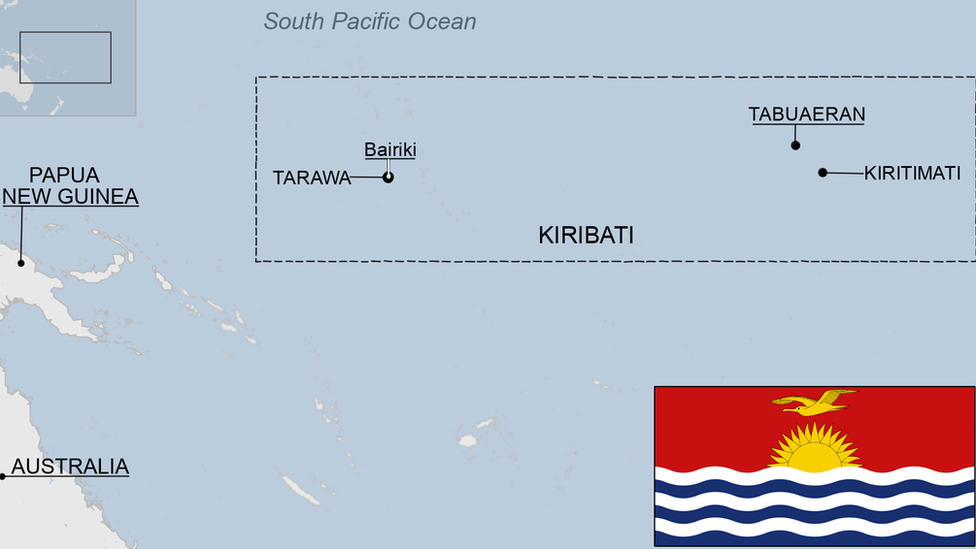

Kiribati consists almost entirely of tiny strips of land which barely peek out above a vast and relentless Pacific Ocean.

Tarawa, the main island where Mr Teitiota now lives, is 3m (9.8ft) above sea level at its highest point. It's obvious why people here are worried about sea level rise.

Tarawa is the capital of the vast archipelago nation of Kiribati

Experts who study atolls point out that as erosion happens on one side of an atoll, sand often accumulates on the other. The sea might not win a complete victory, external, because atolls shift and change and even rise with the tide.

But the shore line is likely to move, so Mr Teitiota and others who live by the water worry that their sea walls or houses might wash away.

Mr Teitiota, his wife and three children are staying at his brother-in-law's house. It's a basic cinder block box with no chairs and virtually no modern conveniences.

He has two penned pigs in his yard and a pack of stray dogs scratch themselves under the palm trees. He warns me about the brown dog. That's the dangerous one. And he doesn't like it being so close to his kids.

The family relies on rainwater for drinking. The tank is too small, so they struggle to get enough. It's a bitter irony in a place that's constantly threatened with inundation.

They pump water from the ground too, but it's filthy. The groundwater here is just below the surface, which makes it vulnerable to contamination from humans and animals above.

Stray dogs frequent the Teitiota family's block

The family pumps water from the ground but it is not very clean

They only use groundwater for washing, but it's making his children sick. All of them have skin problems. Hopefully, it's just an annoyance.

But childhood illness is a real concern here. Infant mortality, external is higher in Kiribati than in Bangladesh, and the water is a contributing factor.

While there are solutions to some of these problems, they cost money, and Mr Teitiota hasn't worked since he returned. The prospects aren't bright in a country where unemployment tops 30%.

Mr Teitiota's lawyer, Michael Kidd, is still outraged that he was deported.

"I'm amazed that the New Zealand government seems to think it's okay to send people back to those conditions," he says.

Mr Teitiota's current situation shouldn't be a surprise to anyone who heard his case. In fact, it's exactly what he told them would happen. And the various tribunals and courts that considered his case accepted he was telling the truth.

What they didn't accept was that the dangers were imminent, or that they were due to "reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion," as the refugee convention requires.

Mr Teitiota's children all have skin problems from the groundwater they use for washing

Mr Kidd sees politics in the mix. There are potentially hundreds of millions of people in low-lying areas that could be affected by sea level rises. He wonders if wealthy countries fear that cases like Mr Teitiota's could turn climate migration from a trickle to a raging torrent.

But there hasn't been a dramatic exodus just yet. The New Zealand immigration department sets aside 75 places a year in a lottery for migrants from Kiribati, and at the moment it can't fill them.

President Anote Tong suggests that is because things aren't desperate enough yet.

"It's not a critical issue yet. I think if there are people who migrate now, I hope they would do it out of choice. But as to the question, is it so critical that people would be regarded as refugees? My answer would be no, not at this point in time."

And yet, the annihilation of his country is something he discusses more than any other head of government.

He just hosted a conference which considered questions such as, what happens to a country's fishing rights if it ceases to be a country? Do people retain citizenship if a country no longer exists?

Kiribati was among several low-lying island nations flooded by Cyclone Pam in March this year

Perhaps it shouldn't be a surprise that Mr Teitiota worries about it.

"I think being a refugee is the best way of protecting myself. Especially if something happens to Kiribati," he says.

The refugee convention was a product of post-war Europe, conceived and written long before climate change became a global issue.

Cases like Mr Teitiota's don't really fit, according to Jane McAdam, a law professor at the University of New South Wales who has written extensively about refugees and climate change migration.

But if the refugee convention isn't the right mechanism for people fleeing natural calamities, (and there were 19.3 million of them in 2014, external) then what is?

A new international framework called the Nansen Initiative is emerging. It's a protection agenda based on "international consensus", "standards for treatment" and "operational responses to disasters."

"It's not a one size fits all approach, but a disaster toolkit", says Jane McAdam.

But it's still very much a work in progress, and there's no guarantee it would leave Ioane Teitiota better off.

"I wanted to stay in New Zealand because it's a better life there," he says.

For the moment, it appears he's stuck here in Kiribati.

- Published24 September 2015

- Published26 January 2024