How a forgotten British captain is a hero in Myanmar

- Published

In World War Two, British Capt Peter Robert Sandham Bankes led a company of Chin tribesmen in Burma - now known as Myanmar - in repelling the Japanese advance on the nearby border with India. He was killed in those remote hills 72 years ago, but as journalist Mark Fenn found, he remains a hero in the eyes of local people.

Editor's note: Mark Fenn completed this piece for the BBC shortly before he died suddenly in Thailand last week - it is published here with the permission of his family.

When the Japanese invaded Burma in 1942, many Burmese initially supported them, seeing them as liberators from the hated British colonial rule.

But in the Frontier Areas, hill tribes such as the Chin, Kachin, Karen and Karenni remained fiercely loyal to the British. Many were Christian, and had been favoured by the colonial authorities.

A British soldier escorts a captured Japanese sniper in Pegu, Burma - British troops were seen by many Burmese hill tribes as having protected them from Japanese brutality

As the Japanese advanced, British soldiers and civilians were forced to retreat to India. But a few officers volunteered to stay behind, while others later trekked or were parachuted in to help raise guerrilla armies in the hill-tribe areas.

These included men like Lt Col Edgar Peacock in the Karenni hills and Major Hugh Seagrim in the Karen lands - brave and often eccentric men with a great deal of respect for the local cultures and the troops they led.

Lt Col Peacock was an old Burma hand with a deep knowledge of the terrain he worked in, a keen hunter and early wildlife photographer.

Maj Seagrim - also the son of a Norfolk clergyman - was nicknamed Grandfather Longlegs by the Karen for his lanky physique.

He was a devout Christian who "often said that he would sooner be a postman in Norfolk than a general in India", according to the author of his 1947 biography, the Australian journalist Ian Morrison.

Both won admiration and respect from their men, and are fondly remembered in the areas they served in to this day.

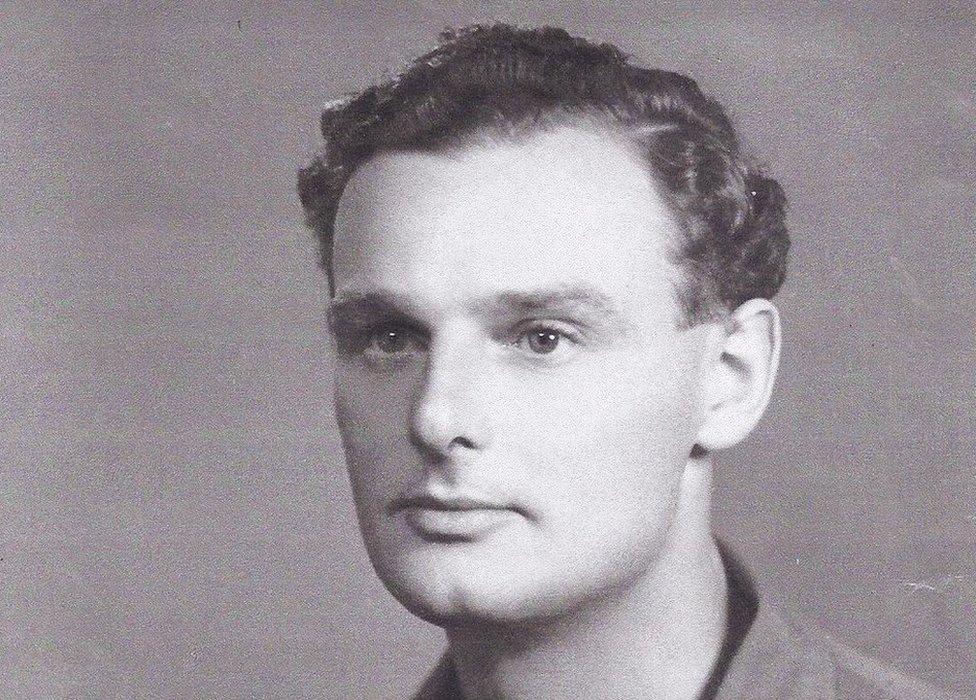

Capt Bankes was another. The son of a Norfolk clergyman, he read forestry at Oxford, where he rowed for the university and helped to run a camp for unemployed men from the East End of London.

After graduating he took a job with the Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation, which had large interests in teak in northern Burma.

'Long legs and bounding energy'

In 1940, back in the UK on leave, he married 19-year-old Pearl and they sailed from Liverpool to Rangoon - now Yangon - in October that year.

After being awarded a warrant in the Army of Burma Reserve of Officers, he was attached to the Chin Levies, a ragtag group of tribesmen charged with stopping the Japanese advance on India.

Peter Bankes managed to raise the funds to travel to Myanmar to find the resting place of his father

His son Peter, who is now 71, from Salisbury in the UK, says that at the time, they were provided with muzzle-loading flintlock rifles from the Boer War, and also armed themselves with swords, knives and spears.

Later they were provided with Lee Enfield rifles and used weapons taken from enemy soldiers they had ambushed and killed as they waged guerrilla warfare against the Japanese in the mountainous region.

"He became known as the 'Chin Express' due to being the fastest climber in the hills, with his long legs and bounding energy," said Peter.

"The Chin warriors played a great part in holding hundreds of miles of frontline, and preventing the enemy from crossing into India."

But Capt Bankes didn't live to see the end of the war.

He was shot and killed in November 1943 by a renegade Chin soldier he had reprimanded twice for sleeping while on sentry duty - the soldier went off to collect his reward from the Japanese.

Capt Bankes was just 32 years old, and for his service in the Chin hills he was posthumously awarded the Military Cross for "gallant and distinguished service in Burma and on the Eastern Frontier of India".

Tracking down a local legend

Meanwhile, his pregnant wife Pearl had fled to India, where she was active in the newly-formed Women's Auxiliary Service of Burma, providing crucial support for troops. She was herself mentioned in dispatches for distinguished service in May 1944.

Myanmar has been opening up in recent years since the end of military rule

Peter was born in Assam, India, in July that year, and returned to England when he was around a year old. There were still connections with Burma - his godfather was the British soldier and elephant expert James Howard Williams, also known as Elephant Bill, who was known for his work in the teak industry and the Burma campaign.

But after the war and Burmese independence, the country became increasingly poor and isolated under successive military regimes.

Myanmar has opened up in recent years, and last November held elections won by the National League for Democracy, led by Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi.

With the country becoming more open and accessible, Peter planned a trip and decided to find out more about his father. He was helped by various people, including members of the small British charity Help for Forgotten Allies, external.

"We are striving to raise financial support for the surviving old soldiers of the hill tribes of Burma - the Chin, Karen, Kachin etc," said board member Peter Mitchell.

"The hill peoples fought so courageously for Great Britain against the brutal Japanese invasion of Burma in World War II. They loyally supported Britain, at our time of gravest peril, with great bravery and at huge and continuing cost to themselves.

"They are now in the greatest need towards the end of their lives."

Another great help was retired psychiatrist Desmond Kelly, who has written a book about the campaign in the Chin hills based on the letters of his own father, Lt Col Norman Kelly, a friend and comrade of Capt Bankes.

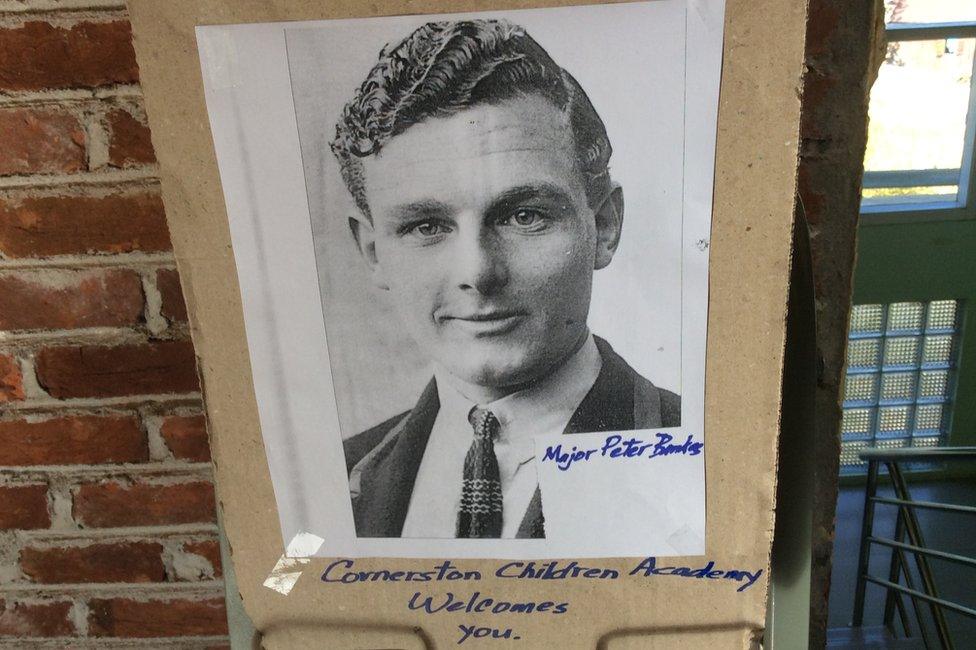

Capt Bankes's picture is on proud display at the school in Tiddim

He put Peter in touch with the Rev Thang Khawm Pau, a Baptist minister and headmaster of a school in the town of Tiddim.

Mount of Gentleman Bankes

The Chin people are very grateful to the British, who built roads and saved them from the Japanese during the war, the reverend says. Japanese soldiers had a reputation for brutality during the Burma campaign and were widely feared.

The minister made extensive enquiries and told Peter his father's grave was located about 30 miles north (48km), in the deserted village of Lampthang.

An elderly resident of a nearby village told him the location was known as "Bank manga mual", which roughly translates as the "Mount of Gentleman Bankes" in the Chin language.

With some friends, he visited the grave and took three scraps of bone, which a visiting Briton helped take back to Peter in England.

Experts say they appear to be from a human heel and ankle, but they would probably be unable to carry out conclusive DNA tests.

Reunited in death

However, Peter is sure the bones are from his father, as he believes he was the only British or Commonwealth soldier killed and buried in the area during the war.

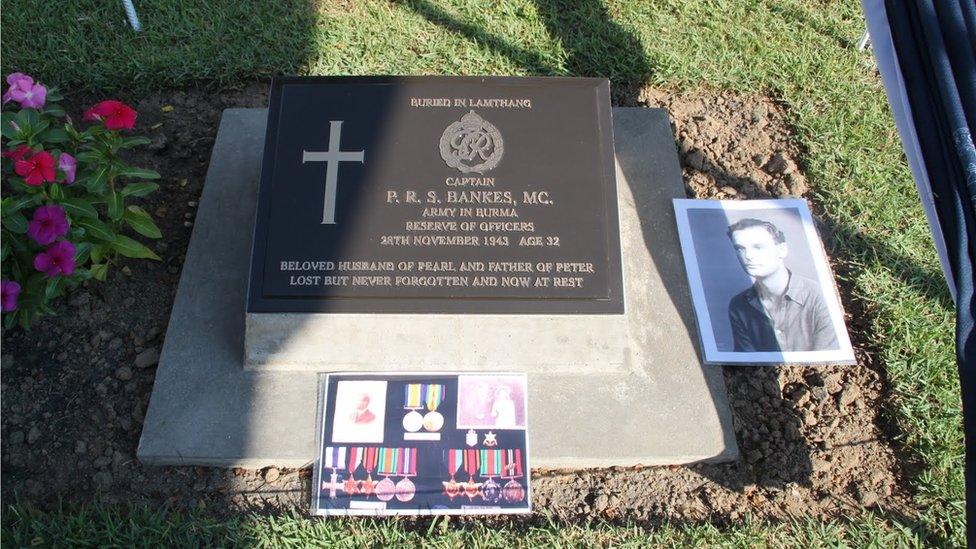

The unveiling of a plaque for Capt Bankes in a cemetery outside Yangon was attended by local officials and some curious tourists

When his mother Pearl died in June last year, at the age of 94, he placed the bones in a velvet sack along with some earth from the Chin hills, and the undertaker placed it in her hand - thus reuniting them in death, 72 years apart.

And when Peter visited Tiddim in January last year with his wife, Jennie, he was astonished to hear that his father is considered a local hero there, with several photographs of him displayed in a local school and pupils urged to honour the man who is said to have sacrificed his life for the Chin people.

Although he couldn't visit the grave itself, as the area is off-limits to foreigners, Peter was happy to see where his father had served.

"We were about five miles from my father's grave, and I was right in an area where he operated, and indeed he probably used this route on his regular trips on foot back to Tiddim for briefings," he said.

'Now at rest'

Peter returned to Myanmar in November and attended a Remembrance Sunday service at the Taukkyan War Cemetery outside Yangon, where his father's grave is listed as unknown on a stone pillar.

The plaque secures Capt Bankes place in the history of the war in Burma

Afterwards, he unveiled a simple bronze plaque on a stone plinth, paying tribute to Captain P.R.S Bankes, MC, "beloved husband of Pearl and father of Peter. Lost but never forgotten and now at rest".

He was expecting a small, private ceremony but to his surprise he was joined by the British ambassador, some tourists and a group of foreign diplomats who had just attended the main remembrance service for those lost in Burma during World War Two.

"I have to say, I was gobsmacked," he said afterwards. "I thought I was just going to have a little ceremony and I couldn't believe it when I saw all the ambassadors there. That was the icing on the cake, there's no doubt about it."

It was a "very emotional few minutes", said Peter, himself a former Royal Marine, as he remembered the father he never met at the end of his long quest.

"I believe that he can now, at last, rest in peace."

- Published19 October 2014

- Published15 August 2015

- Published12 August 2015

- Published18 July 2015