Tea, rivalry and ambition in the Calais 'Jungle hotel'

- Published

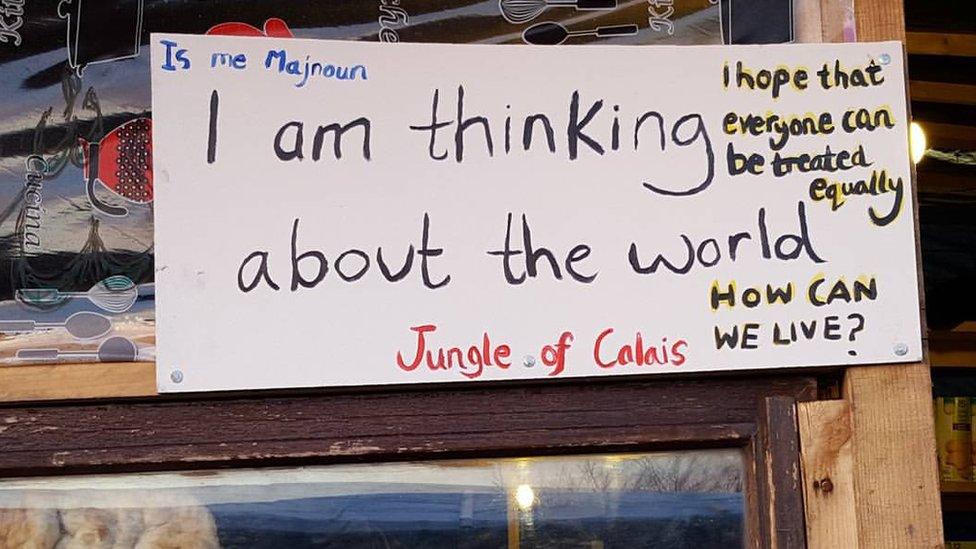

Improvised cafes and guest houses serve the migrant community in the Calais 'Jungle' camp

As bulldozers continue to clear part of the makeshift Calais camp known as the Jungle, some migrants continue to resist the move into container accommodation.

Feet up and cigarette in hand, Rahim is lying on a wooden crate that serves as a bed, listening to Shakira on his laptop.

The thin plywood and plastic walls of his makeshift hut offer little protection against the cold, damp winter air, and he's wrapped in a blanket to keep warm.

Rahim is from Kabul and arrived in France six months ago in search of a better life.

A handsome and self-assured young man in his late 20s, dressed in a smart black shalwar kameez, he describes how he set up shop in the Afghan section of the infamous Calais jungle camp, opening a cafe offering cheap food and shelter for new arrivals.

Business enterprise

The cafe which Rahim calls his "hotel" may be no more than a rickety shack, but business is booming.

As he tells his story, a succession of young Afghan men in cheap leather jackets come and go.

Some bring in water from a nearby stand-pipe. Others stir the cooking pots on a portable gas stove in the kitchen area.

Overhead, the walls are lined with wooden shelves full of jars of Indian spices and cans of beans and peas.

'I've got 20 men working for me here, and I pay them 25 euros a day," Rahim tells the BBC.

He even earns enough to send money back home.

Migrants told the BBC they are not looking for hand outs

A taste of home: Migrants eating Afghan food in a makeshift cafe

Destination UK

Rahim's story is a clear illustration of the complex and often perplexing realities of life in the Calais camp.

He openly admits that his life wasn't in danger in Kabul.

"Thank God we were always well off," he says with a smile, "I never worked a day in my life."

But Rahim, and many young single Afghan men like him in the camp are all in search of something life back home could never offer - the opportunity to make something of themselves.

They do not think the world owes them a living. But they definitely think the world owes them the chance to try and live their dream.

For most of the Afghans that means finding a way - somehow - to reach the UK.

"The French are racist, there are no jobs here," says Rahim. "At least in Britain we can find a job or do business."

Everyone is waiting for their chance to scale the fences around the port and smuggle themselves onto a truck heading for the UK.

One of Rahim's friends Khan Zaman has already made two failed attempts.

"Last time I hurt my leg and ended up in the hospital," he says. "After that I decided to stay put for a while and make some money."

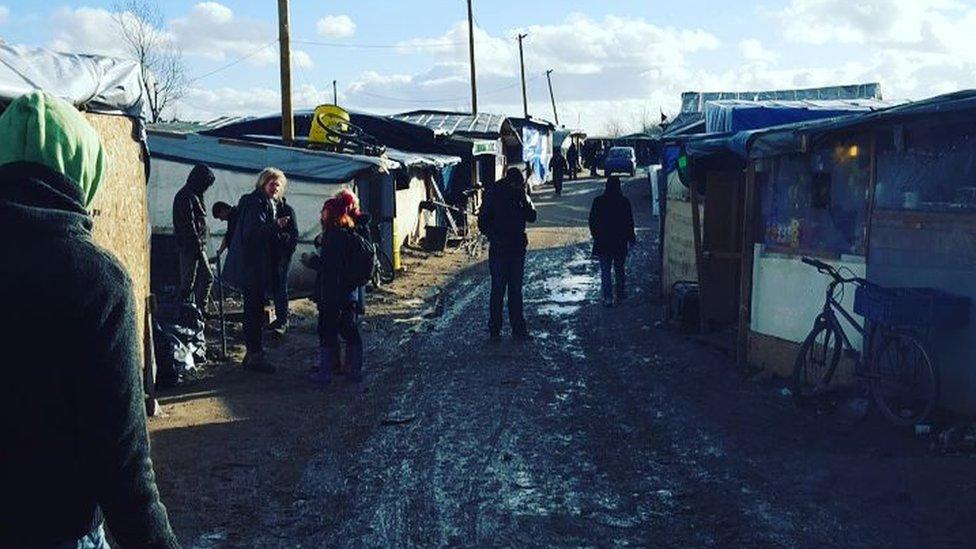

Migrants stand outside a shelter in the Calais camp

In recent weeks the determination to make it to the UK has put the Afghans on a confrontation course with the French authorities.

Local police are trying to clear parts of the camp close to the main road, and to encourage migrants to move into new purpose-built shelters.

"I'm not going anywhere," says Rahim. "It's either Britain or right here! How am I supposed to earn a living in the new camp?"

There have been regular night-time confrontations between the young Afghans and French police.

Rahim and his friends show us footage on their mobile phones of riot police firing tear gas at crowds of young men hurling stones back at them.

Among the piles of rubbish building up all over the camp, there are many tear gas canisters.

The Afghans are not happy with this state of affairs, but neither, for different reasons, are some of the other residents of the camp.

In another section of this vast and sprawling place there are many families from Syria and Iraq. It's here that most of the estimated 400 women and 100 children in the camp live.

Desperate to escape the squalor and freezing cold of the "jungle", these people are keen to move with their children into the safer and cleaner heated container city which the French authorities are building.

Some told the BBC off the record that they were angry with the Afghans for courting confrontation with the police and giving the whole refugee community a bad name by refusing to move.

Outside temperatures can drop to close to zero in Calais

Back in the Afghan section, night is drawing in and the makeshift cafes are starting to get busy.

At the "Three Star Hotel" - a rival establishment to Rahim's, a cook is busy rustling up beef and chicken soup at bargain prices.

Outside Rahim's cafe there's a commotion.

A group of Somali migrants have turned up selling winter coats and boots.

The Afghans call the Somalis the "black market" and it's clear the two groups have little sympathy for each other.

The Afghans accuse them of selling warm clothing sent by charities. But it doesn't stop them buying things.

"I got this from one of these guys for 20 euros," says Rahim, showing us his coat. "They make a profit from our desperation."

Rahim definitely needs his coat. On this freezing, wet January night the outside temperature is dropping towards zero, and it's not much warmer inside the cafe.

Drug use can be a problem in the camp - and Narcotics Anonymous meetings have been set up

The bare earth floor is covered with a few thin sheets of cardboard, and there's a cold draft blowing through a hole in the wall that's patched over with a plastic bag.

Rahim and his friends and customers are huddled together eating plates of Afghan chicken stew.

The enticing smell of the food mixes with the oppressive smell of sewage that hangs permanently over the camp.

Later there's another smell - hashish, which many young men smoke here to help them get through the long days and even longer nights waiting for their chance to move on.

The names in this story have been changed to protect the identity of the interviewees.

- Published18 January 2016

- Published30 December 2015