Aung San Suu Kyi: Power not presidency in Myanmar

- Published

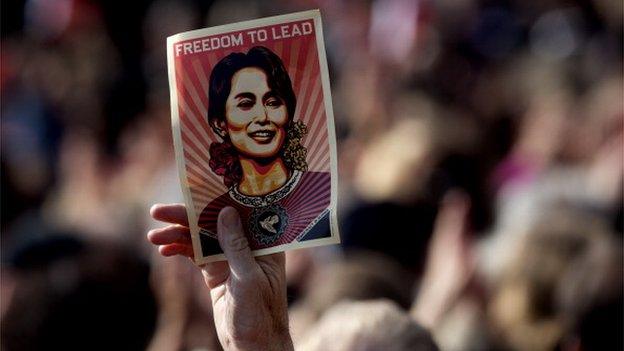

Aung San Suu Kyi has tightened her grip on power in Myanmar

The chances of Aung San Suu Kyi becoming Myanmar's next president have been receding for months.

But as parliament put forward its nominations for the top job, the situation became clear: there would be no last-minute deal, no President Suu Kyi.

Those expecting a Nelson Mandela ending to this incredible story will be disappointed. But for Suu Kyi and her many supporters little has actually been lost.

This anticlimactic outcome strengthens her politically and diminishes the military in the eyes of the Burmese people.

The generals' inflexibility, in the face of a huge popular mandate, has set the tone for what looks likely to be a period of confrontation between them and the newly elected democrats.

It was in November last year that Suu Kyi's party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), swept the board in the long-awaited general election.

The NLD won nearly 80% of the contested seats, external and everyone, even the army, external, agreed that the Burmese people had not just voted for change, they had voted for Suu Kyi to lead.

Emboldened by the result, the former political prisoner reached out to her long-time adversaries. In the past four months she has held three meetings with Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing. Suu Kyi was exploring the possibility of a grand deal.

What the NLD leader needed was the army's approval for a legally dubious move. She wanted parliament to temporarily suspend the part of the constitution that bars her from becoming president.

Clause 59F, external famously disqualifies anyone whose spouse, children, and even spouses of children, have foreign passports. Suu Kyi's two children by Oxford academic Michael Aris are British.

Supporters of the clause say it protects the country's sovereignty, but many believe it was drafted by the military to close the door on Suu Kyi. To open that door, the Burmese army would have demanded concessions.

Suu Kyi met Myanmar's senior general Min Aung Hlaing to try to strike a deal

That could have meant giving the military the right to choose the chief ministers of several states, and securing promises that the army's many business interests would be left alone.

Most importantly, the military is almost certain to have insisted that attempts to chip away at its political power be put on the back burner.

So beneath the feel-good headline of "President Suu Kyi", the army would have consolidated its political role.

It's not clear why the grand deal didn't happen. Perhaps the army just couldn't stomach the idea, or maybe Suu Kyi refused to concede enough. For whatever reason, the talks broke down.

New landscape

So what, then, will the new political landscape look like?

Suu Kyi famously said before the election that she would be "above" whoever she picks to be president.

It is clear that Htin Kyaw has been selected primarily for his loyalty. All Suu Kyi will have to do is pick up a phone to flex her presidential power by proxy. She has lost nothing there.

Unencumbered by any deal with the army, Suu Kyi will be freer to pursue her campaign platform from the 2015 election.

Myanmar nationalists have demonstrated against Suu Kyi becoming president

Her authority is unchallenged within her party and she will now remotely command both presidency and parliament. One of her priorities is likely to be a renewed bid to change the constitution to reduce the army's power.

The unelected army representatives have already sampled the new order. Suu Kyi's MPs are demanding that deals made by the army and the former government be re-examined.

In a rare moment of drama, all the men in green uniform stood up in the house in protest.

In the immediate aftermath of the election, Suu Kyi spoke of being inclusive and creating a government of national unity. That was before the army rejected her overtures.

It is expected that the government Suu Kyi leads will be a mix of NLD officials and technocrats. But will she now be in the mood to find room for those from the military party, the USDP? Quite possibly not.

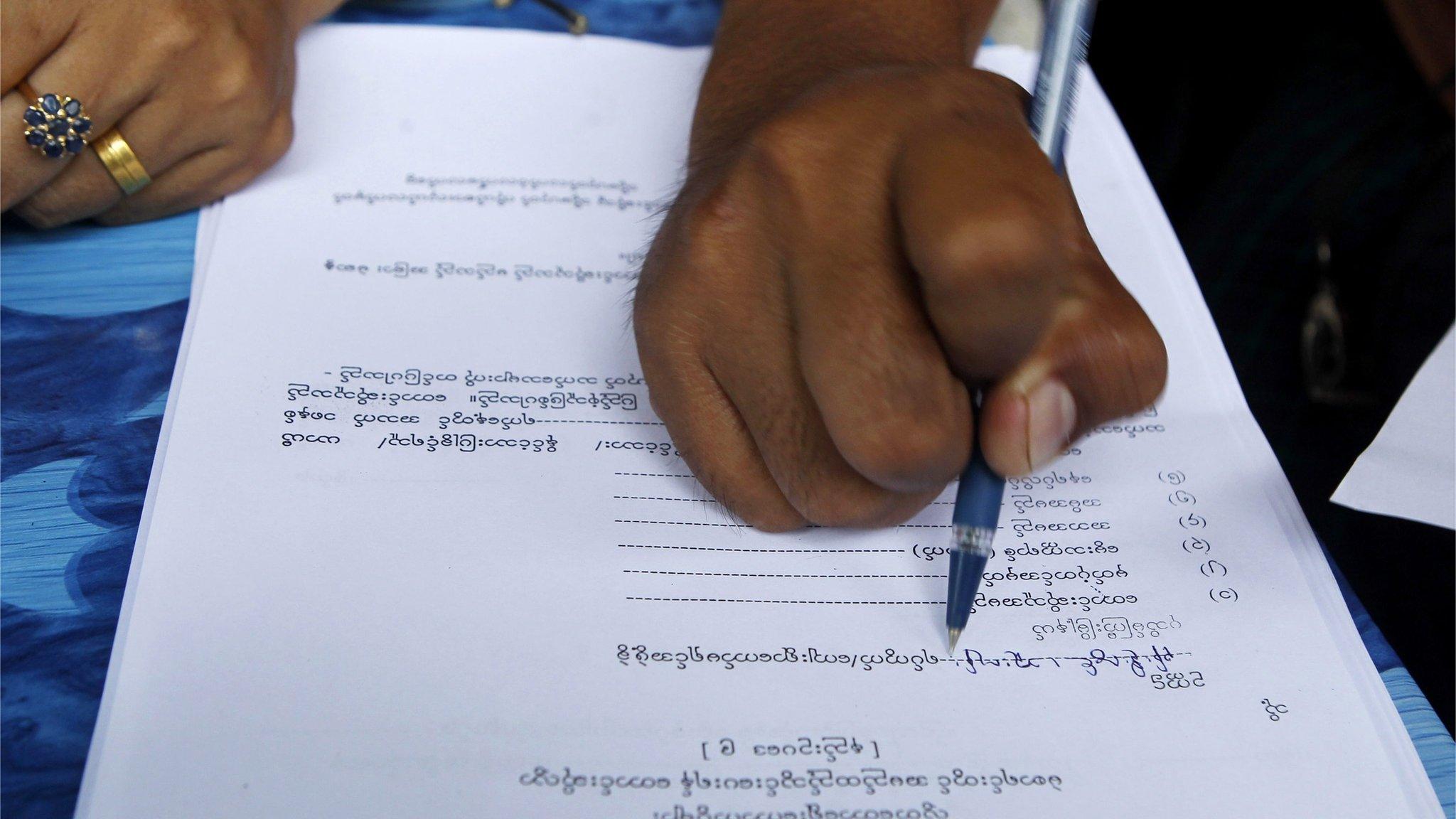

The 2008 constitution will be the main limit on Suu Kyi's power. Drafted by the generals, and approved in a sham referendum, it ensures the military retains its political role.

The key security ministries (home, defence, border affairs) are appointed not by the president but by the army commander-in-chief.

A quarter of the seats in parliament are also reserved for soldiers. That is not enough for them to block legislation, but sufficient to scupper any attempts to amend their constitution.

Much has changed in Myanmar, but the Burmese army has not budged one inch from the red lines it put into the constitution.

The democratic experiment, economic reforms and the emboldened Suu Kyi remain in a controlled space that the military designed and now seem intent on preserving.

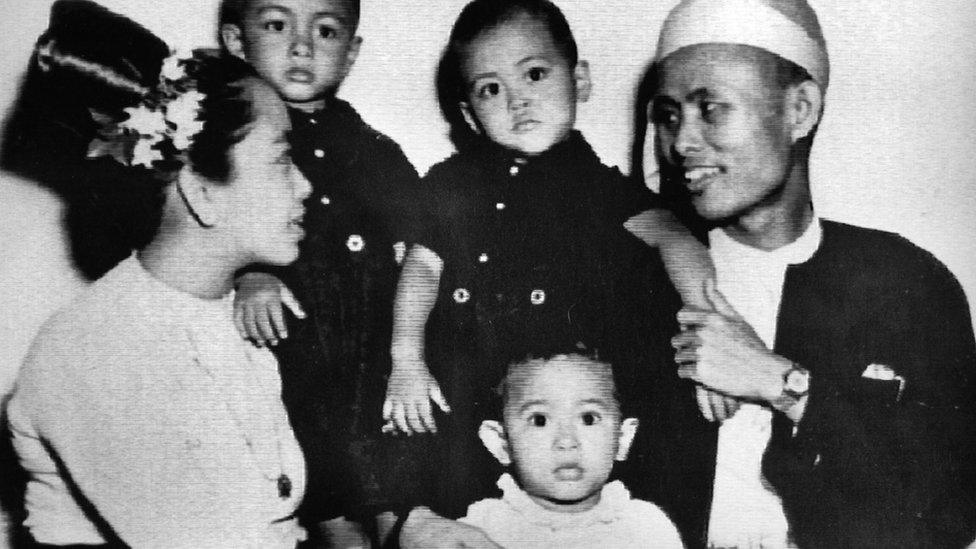

Suu Kyi (centre) was a toddler when her father was assassinated

Aung San Suu Kyi

Daughter of Myanmar's independence hero, Gen Aung San, assassinated in July 1947 when Suu Kyi was only two.

From 1964, studied philosophy, politics and economics at Oxford University, where she met her future husband, academic Michael Aris.

Returned to Rangoon in 1988 to look after her critically ill mother during the midst of a campaign for democratic reform.

Organised rallies and travelled around the country, calling for peaceful democratic reform and free elections.

Demonstrations brutally suppressed by the army, which seized power in a coup in September 1988, placing Suu Kyi under house arrest the following year.

Her party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), won a national election in 1990 - but the junta refused to relinquish power.

Suu Kyi spent protracted periods under house arrest until she was finally released unconditionally in 2010.

Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991.

Led the NLD to a majority win in Myanmar's first openly contested election in 25 years in November 2015.

- Published29 January 2016

- Published28 January 2016

- Published1 February 2016

- Published3 December 2015

- Published8 July 2015