Japanese satellite Hitomi: Lost in space?

- Published

The satellite was called Astro-H at launch, but renamed Hitomi in space

Dozens of Japanese scientists and engineers are scrambling to save a satellite - and more than a quarter of a billion dollars of investment - tumbling out of control in space.

Hitomi, meaning the pupil of the eye, was launched last month.

It was designed to study energetic space objects such as supermassive black holes, neutron stars, and galaxy clusters, by observing energy wavelengths from X-rays to gamma-rays.

But time is now running out to save the mission.

The satellite was carried into space on an H-2A rocket in February

What happened?

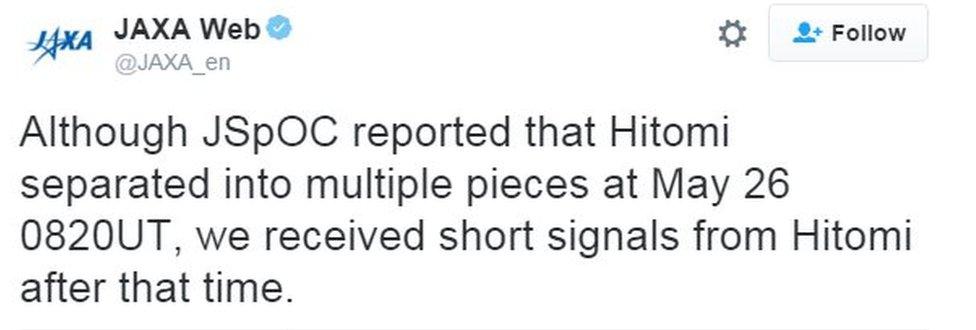

On Saturday, the US Joint Space Operations Center (JSpOC), which tracks space debris, detected five small objects around the satellite.

Ground control in Japan managed brief contact with the spacecraft after that, but then lost contact.

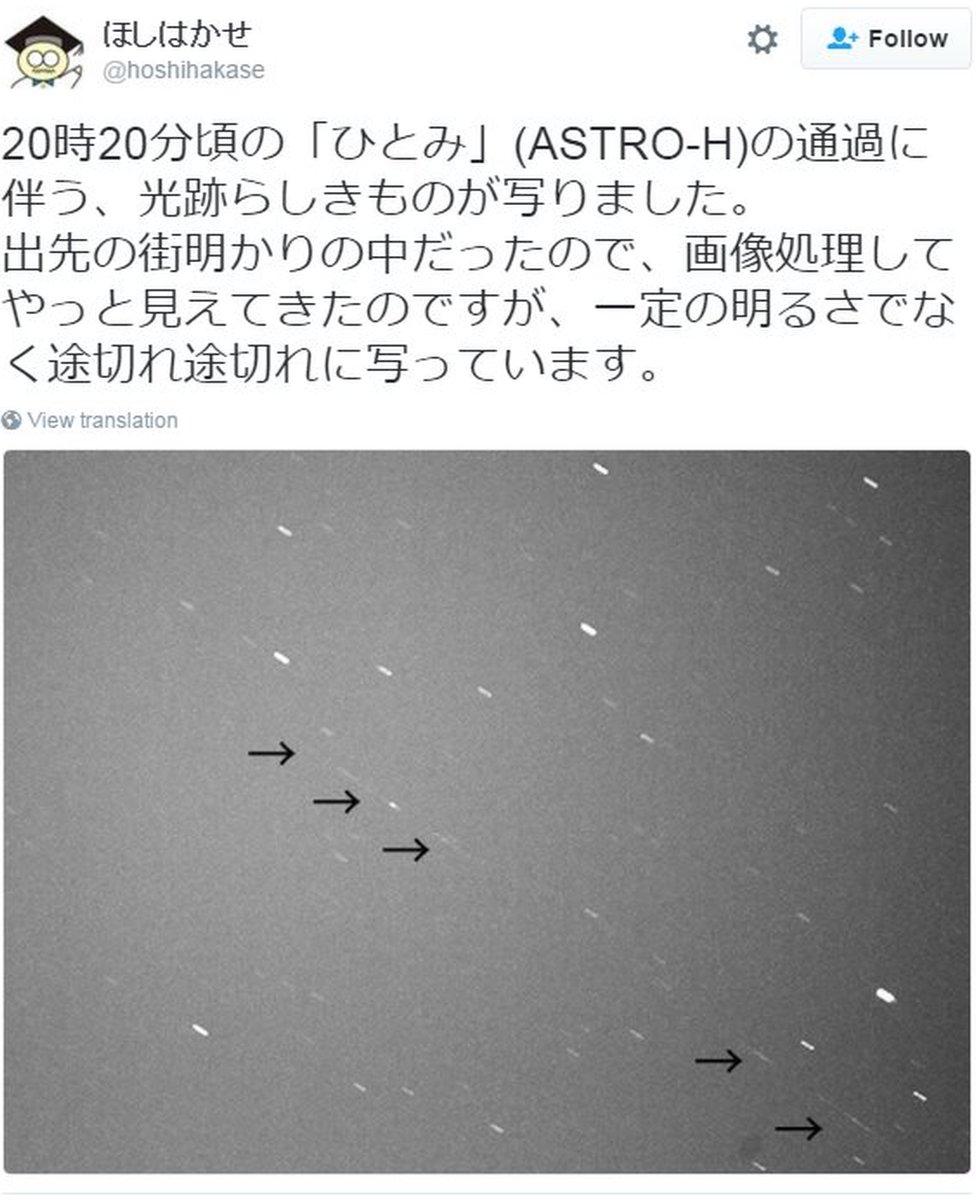

The satellite also appeared to show a sudden change of course, and observers on Earth have seen it appearing to flash, suggesting it may be tumbling.

The next day, JSpOC referred, external to the event as a "breakup", although experts have clarified that Hitomi may well be mostly intact.

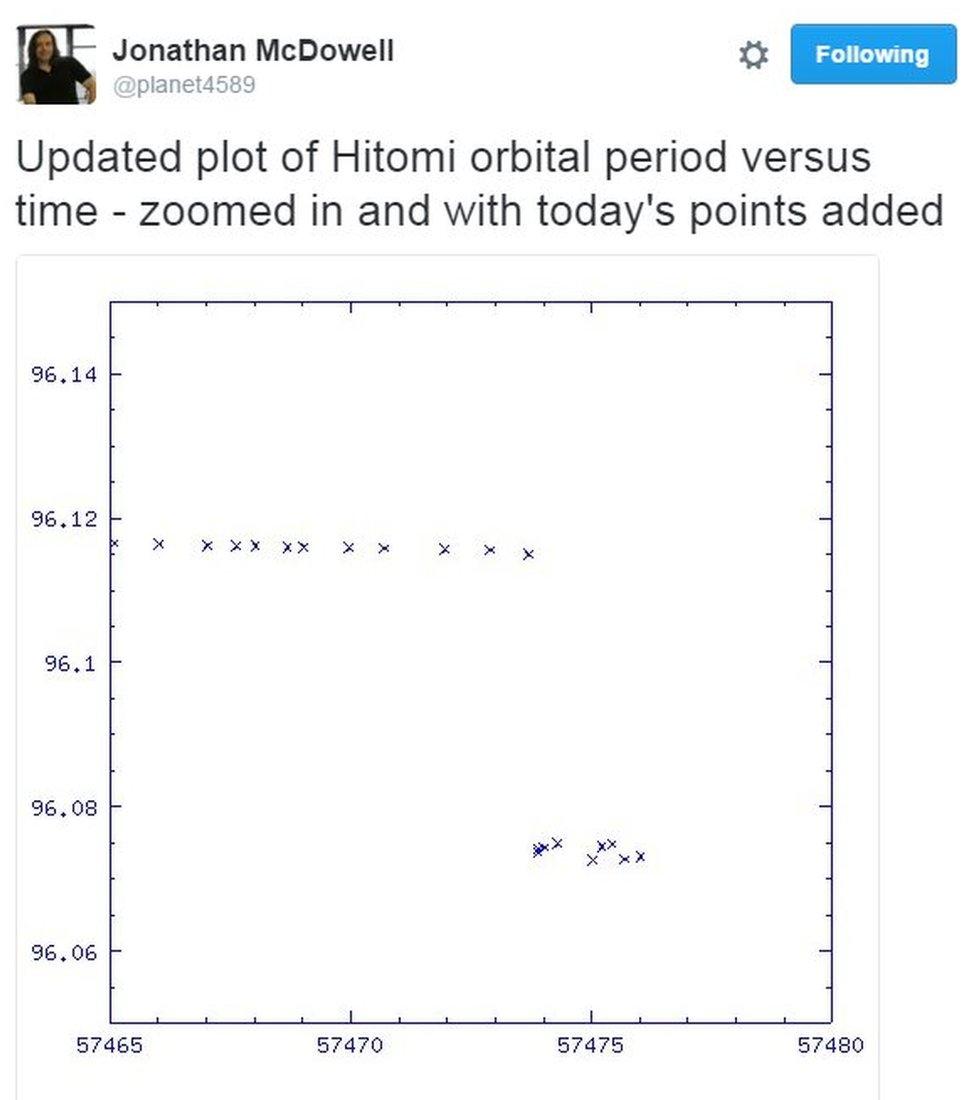

Charts appear to show Hitomi went suddenly off course

What has happened to it?

The Japanese space agency (Jaxa) told the BBC it did not know right now, and that the agency was still trying to restore communications with Hitomi.

Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told Associated Press that two possibilities were that the spacecraft might have suffered a battery explosion or a gas leak, putting it into a spin and out of contact.

"To hear that they've run into this piece of bad luck, it's so very sad. I know enough about how the sausage was made to know that this could have easily have happened to us. Space is very unforgiving."

But Adjunct Prof Goh Cher Hiang, project director of the satellite programme at the National University of Singapore, told the BBC that thanks to monitoring and backup systems, battery explosions were "very rare", and while a leak in the pressurised fuel tanks found on satellites could cause the trouble, "the designer of it can give us some kind of clue".

External factors could also be a reason, he added.

"It could also be from a collision with something in space, either from outer space or a man-made object already in space."

Small objects are not necessarily detected by ground radar, he points out, and with even tiny pieces a "collision can cause serious damage" because they are travelling so fast.

Satellites missing in action

Despite decades of practice, getting satellites into space in perfect working order is still tough.

A Russian defence satellite was lost last December after it failed to separate from the rocket carrying it to orbit

Nasa's Earth-observing satellite Glory did not make it into orbit in 2011, when the protective nose cone on its launcher failed to separate

In November last year, a US defence "nanosatellite" launched on a new type of rocket and learnt the hard way that being first is not always best, when it broke up after lift-off

In 2000, the rocket carrying Japan's Astro-E satellite crashed into the sea

Suzaku, Astro-E's successor, made it into space, but its main instrument was disabled by a helium leak in 2005

Proving that you should never give up though, Jaxa recently got its Akatsuki spacecraft into Venus orbit a whole five years after it was thought lost because of a failed engine burn

Alexis, a US X-ray satellite, went dark after launch in 1993, before engineers managed to re-establish contact, months later

How rare is it to lose a satellite?

"In general, it's rare," Prof Goh told the BBC. "But it's not impossible - it's the reason a lot of people buy satellite insurance, just in case."

And "a complete failure of the operation", in which nothing can be salvaged of the original mission, is rarer still, especially for "reputable institutions" like Jaxa.

Observers on Earth noticed the satellite's brightness was changing as it crossed the sky, suggesting light reflecting off it as it tumbles

What now?

If it turns out to be impossible to save, it will create a financial black hole of its own. And the 31bn yen ($273m; £191m) it cost the Japanese government does not include instruments supplied by Nasa, the Canadian Space Agency, or the European Space Agency, either.

It will also be the third Japanese X-ray astronomy satellite to be lost or critically affected by malfunction. In 2000, the rocket carrying the Astro-E satellite crashed into the sea, and while its successor, Suzaku, made it into space, its main instrument was disabled by a helium leak in 2005.

But Jaxa has pulled off off seemingly hopeless space recoveries before. Its engineers managed to get the Akatsuki probe into Venus orbit in December last year after the spacecraft had been drifting in space for five years.

Is there reason for hope?

The fact that the agency still had contact with Hitomi for a period even after debris was spotted near the craft is seen by some as a hopeful sign, as it could indicate that it is not critically damaged. Its location is also roughly known.

But a quick recovery will be essential. If the satellite is tumbling in space, as it is thought to be now, it may not be able to capture enough solar energy to power itself before a fix is found.

It all comes down to three things, Prof Goh says: "One, communications; two, power; and three, the computer. First you have to talk to the satellite."

If they can do that, Jaxa has a chance to work out what has gone wrong and how to fix it. But if that is impossible "then you are in trouble".

If it turns out to have been lost, it will be particularly unfortunate for those hoping to study black holes after the news last month that gravitational waves from the collision of two black holes had been detected.

Reporting by Simeon Paterson

- Published12 February 2016

- Published17 February 2016

- Published11 February 2016

- Published11 February 2016