The Vegetarian: How to learn Korean and win awards

- Published

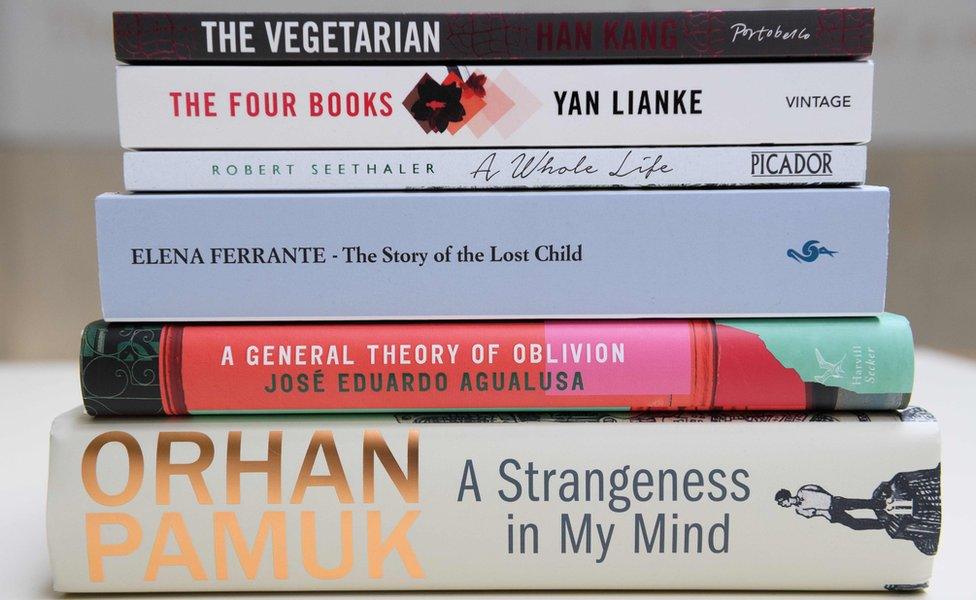

There were six books up for the prize - this year awarded for a single work, for the first time

South Korean writer Han Kang has won the Man Booker International Prize for her novel The Vegetarian, but shares the prize with the translator of the book, Deborah Smith, who only began learning Korean in 2010. The BBC's Steve Evans in Seoul asks how hard Korean really is to learn.

There will be some who argue that Sejong the Great, at his prime in 1444, could rightfully deserve a cut from the proceeds of the Man Booker International prize.

The king's statue stands at the heart of Seoul today and he is holding a book.

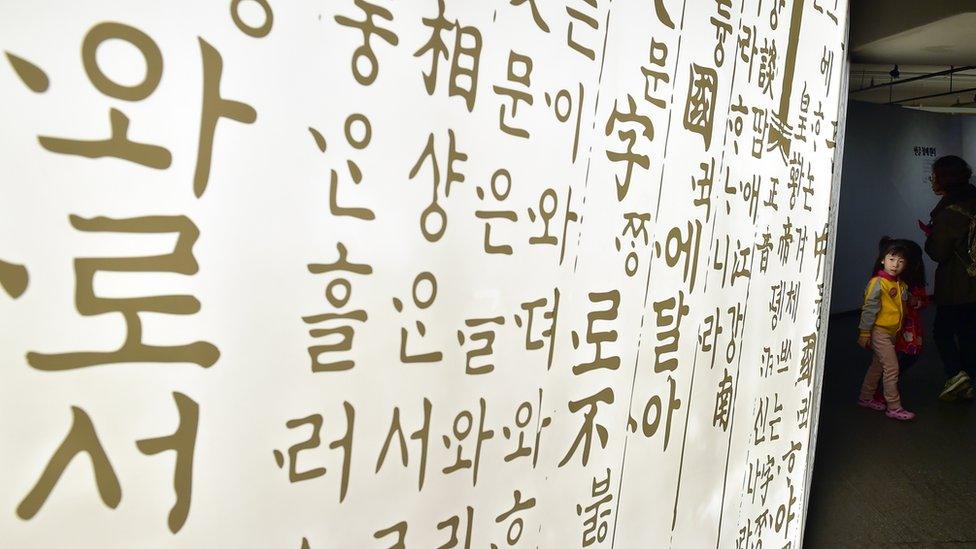

King Sejong the Great, whose statue sits at the heart of Seoul, decreed that a new alphabet should be created for his people.

Around that time, he was wise enough to decree that a new alphabet should be created for the language of his subjects. At his royal instruction, what is now called Hangul in South Korea and Chosongul in North Korea was invented "for the instruction of the people".

It is an alphabet of a mere 28 letters, in contrast to the 3,000 or so Chinese characters. Korean had been spoken before but only written through the Chinese script.

Thanks to King Sejong, the people were given the means to read and write easily.

And as a result of this, one saying goes: "A wise man can acquaint himself with the Korean characters before the morning is done; a stupid man can learn them in the space of 10 days."

Is Korean really any easier to learn than other languages?

Linguists sometimes say that no language is inherently easier to learn than others. Prof Robert Fouser, formerly of Seoul National University, says: "The degree of difficulty in learning Korean depends on which languages the learner already knows."

Hangul, Korea's phonetic alphabet, was meant to give its people the means to read and write easily.

We find languages easy to learn when they are close to the language we already understand. Prof Fouser said that Korean has borrowed many words from Chinese: "The two languages thus share a common vocabulary, but a different word order and grammatical structure.

"Chinese learners of Korean may find Korean grammar as difficult as an English-speaking learner but would no doubt find the vocabulary easy to learn."

But what about English-speakers? The Foreign Service Institute, which teaches languages to American diplomats, puts Korean in the "exceptionally difficult" category.

It reckons that an English-speaker needs 575 to 600 hours of tuition (over 23 or 24 weeks) to learn languages with similarities to English (Afrikaans, Danish, Dutch, French, Italian, Norwegian, Portuguese, Romanian, Spanish and Swedish), but 2,200 hours to reach a similar standard of "general professional proficiency" in speaking and reading Korean.

But don't be put off

Donovan Nagel, a linguist and translator from Australia who has mastered more than a dozen languages, told the BBC he learnt Korean , externalwhile he was in Korea for just over a year. He said he was "communicating fairly well after three or four months and was 'comfortably' fluent by the eight month mark".

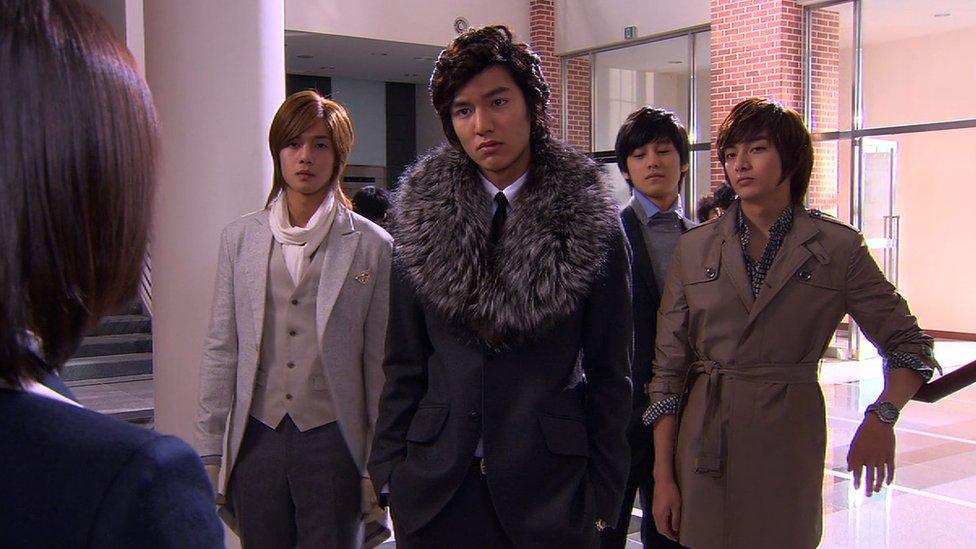

The book focuses on the strain that a woman's decision to become vegetarian - and her husband's refusal to accept it - puts on their marriage

There are pros and cons: the grammar is straightforward. "For the most part Korean is usually pronounced exactly the way it's written, unlike English which is full of words that sound nothing like the way they appear on paper". Think "Leicester" or "Hermione" or, for that matter, "plough" and "cow" or "laughter" and "slaughter" or "take a bow" but "tie a bow".

The verbs in Korean, he says, are a cinch: "Many Korean verbs are actually just nouns connected to the verb to do. For example, to be happy is literally happiness + do = doing happiness."

But translation isn't just learning a language. It is also a creative process and this is why the translator of The Vegetarian could share the prize.

The Vegetarian is a book about about a woman who gives up eating meat in a quest to reject human brutality, but it proves a controversial decision and she becomes subject to the cruelty of her family. It was described by the judges as "uncanny blend of beauty and horror".

It is told in three voices, from three perspectives and the judges said it found "absolutely the right voice in English".

One Korean reader of the novel in both languages told me that the English version is, in its own way, as good a read as the original. He likens translation to a violinist playing a tune hummed by someone else - the vibrato and ornament change the original work, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse.

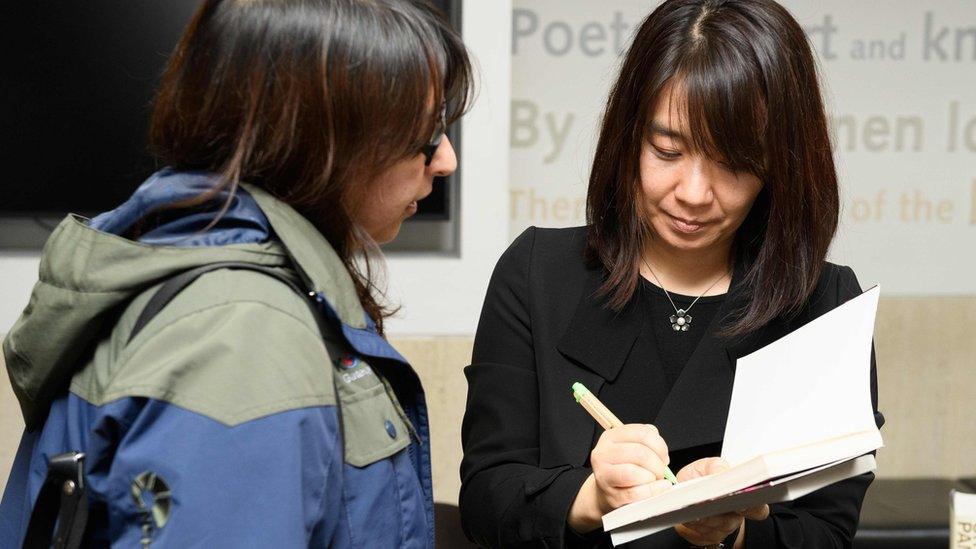

It was the first book Han Kang (right) had published in English

Deborah Smith said she had tried to capture the "rhythm" of the book: "If you're translating a great work of Korean literature, then your translation has to be a great work of English literature, and there's no use quibbling over syntax if that's only going to be hindrance".

The translator deserved the prize. So would King Sejong.

- Published17 May 2016

- Published27 March 2016

- Published24 February 2016