The final image sent by doomed Japanese Hitomi satellite

- Published

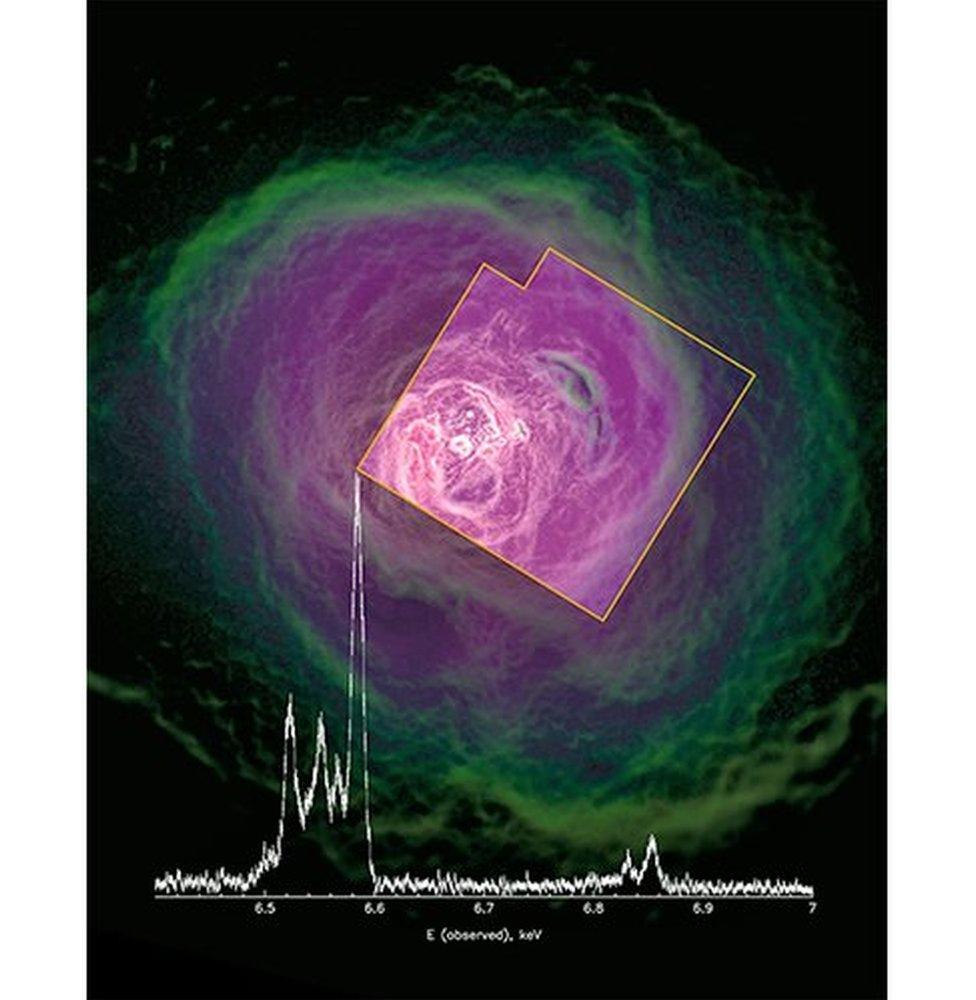

Image of the Perseus cluster taken by Nasa's Chandra X-ray satellite, overlaid with data taken by Hitomi, outlined by an orange box, showing X-rays emitted by iron and nickel in hot gas between the galaxies

A doomed Japanese satellite managed to capture a view of a galaxy cluster 250 million light years away just before it died, scientists have revealed.

Launched in February, the Hitomi X-ray satellite began tumbling out of control in March when contact was finally lost.

Just before its demise, scientists managed to extract data measuring X-ray activity in the Perseus galaxy cluster.

Published in Nature, external, data revealed the movement of gas between galaxy clusters was not as turbulent as expected.

Hitomi, which translates as the pupil of the eye in Japanese, was meant to spend years studying the formation of galaxy clusters and the warping of space and time around black holes.

It cost more than a quarter of a billion dollars - the research was an international collaboration involving the American space agency Nasa, and teams in Japan and many other countries, including one at Cambridge University in the UK.

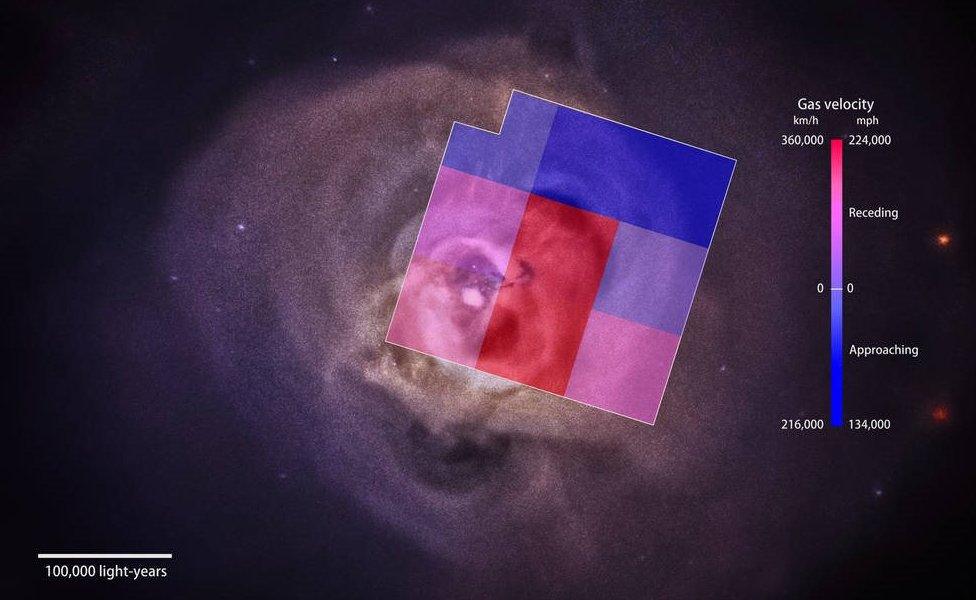

Astronomers using Hiromi's soft X-ray spectrometer mapped the motion of hot X-ray emitting gas in a large part of the Perseus galaxy cluster, overlaid on this image from NASA's Chandra X-ray satellite, with blue indicating areas of fastest gas motion towards earth, and red indicating movement the other way

The Perseus galaxy looks very different to the human eye, which cannot see the X-ray wavelengths that make the gas so visible in X-ray images

Scientists studying the data found that the hot gases between galaxies within the Perseus cluster was travelling at a slower speed - at 540,000 km/h (340,000 mph) - and in a less turbulent way than many expected.

Measuring the turbulence and movement of such gas is important because the size of galaxy clusters is a useful tool for measuring "the parameters of cosmology and the growth of structure in the universe", researchers say.

The gases in galaxy clusters are thought to be particularly hot and dense with a lot of dark matter and a supermassive black hole at the centre of it all. The interaction between all the various gases was thought to be very chaotic so Hitomi's observations appear to have defied predictions.

"The gas is relatively stable and isn't getting pushed around as much as we thought," said Brian McNamara, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, who was part of the research team.

"Hitomi's Perseus observation tells us that we can probably weigh distant galaxy clusters to greater accuracy than we can weigh our own Milky Way galaxy."

The satellite was called Astro-H at launch, but renamed Hitomi in space

Hitomi was lost thanks to a sensor incorrectly detecting a roll in the spacecraft. In trying to correct it, on-board systems sent the craft into a spin until finally the solar panels that powered it are thought to have broken off.

The next time a similar satellite will be launched is in 2028 by the European Space Agency.

The satellite was carried into space on an H-2A rocket in February

- Published29 April 2016

- Published30 March 2016

- Published29 March 2016