Do tourists really go to Afghanistan?

- Published

You may not associate Afghanistan with skiing, but Bamiyan hosts an annual competition

A Taliban attack on a group of foreign tourists in Afghanistan, that left at least six people wounded, is not the first of its kind in the country.

However, while civilian casualties in Afghanistan have reached their highest-recorded level, attacks on tourists are rare.

The fact Afghanistan attracts tourists at all may come as a surprise to some, but a number of companies offer tours to the country where there were more than 11,000 casualties of violence last year.

The UN World Tourism Organization does not receive statistics from the Afghan government on tourist numbers, so it is difficult to track how many visitors are making it there.

But Afghanistan does send the UNWTO data on tourist expenditure.

Those figures show a big drop in the amount of money spent by tourists in the country - from $168m (£128m) in 2012 to $91m in 2014, the most recent year's statistics available.

Muqim Jamshady is chief executive of Kabul-based Afghan Logistics And Tours, which helps organise trips and treks for visitors in safe parts of the country.

He told the BBC that up to 300 tourists used their services in 2003, but the number had now dropped to about 100 a year.

The fall in visitors has come as deaths from violence in Afghanistan have increased.

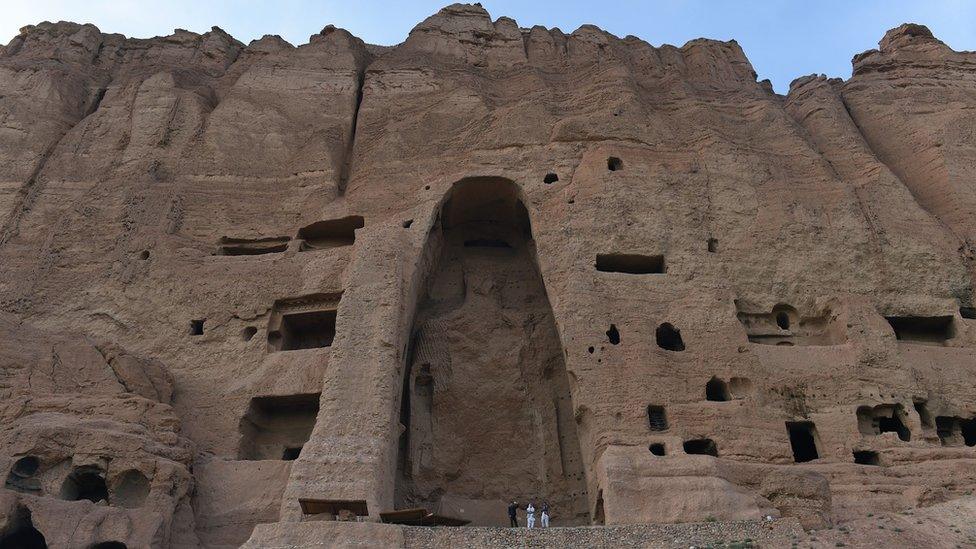

Bamiyan - where the Taliban blew up Buddha statues - is seen as one area relatively safe for tourists

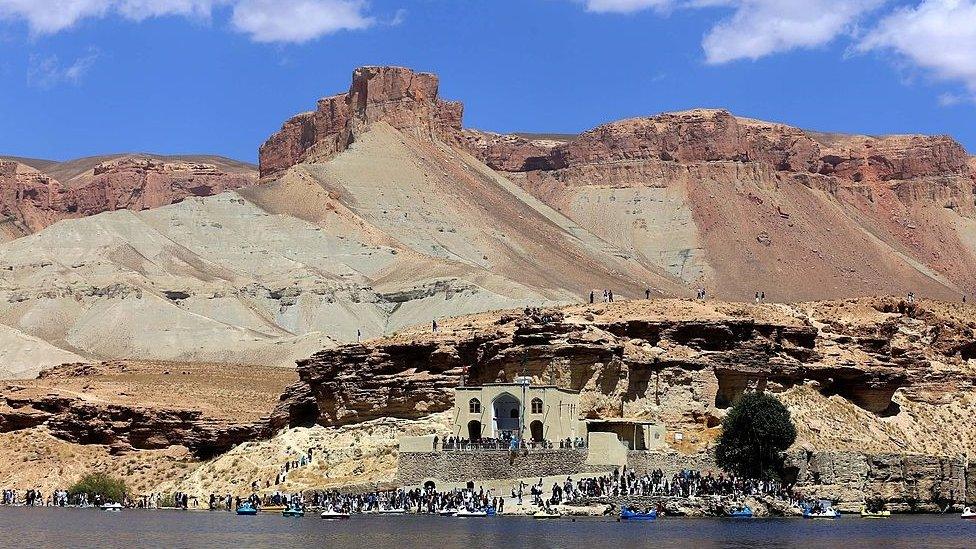

Afghan tourists at a lake on the outskirts of Bamiyan

The British Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) advises against travelling to most parts of Afghanistan, external, adding that "there is a high threat from terrorism and specific methods of attack are evolving and increasing in sophistication".

The US State Department goes even further, external, warning there is a risk of "kidnapping, hostage taking, military combat operations, landmines, banditry, armed rivalry between political and tribal groups, militant attacks, direct and indirect fire, suicide bombings, and insurgent attacks, including attacks using vehicle-borne or other improvised explosive devices".

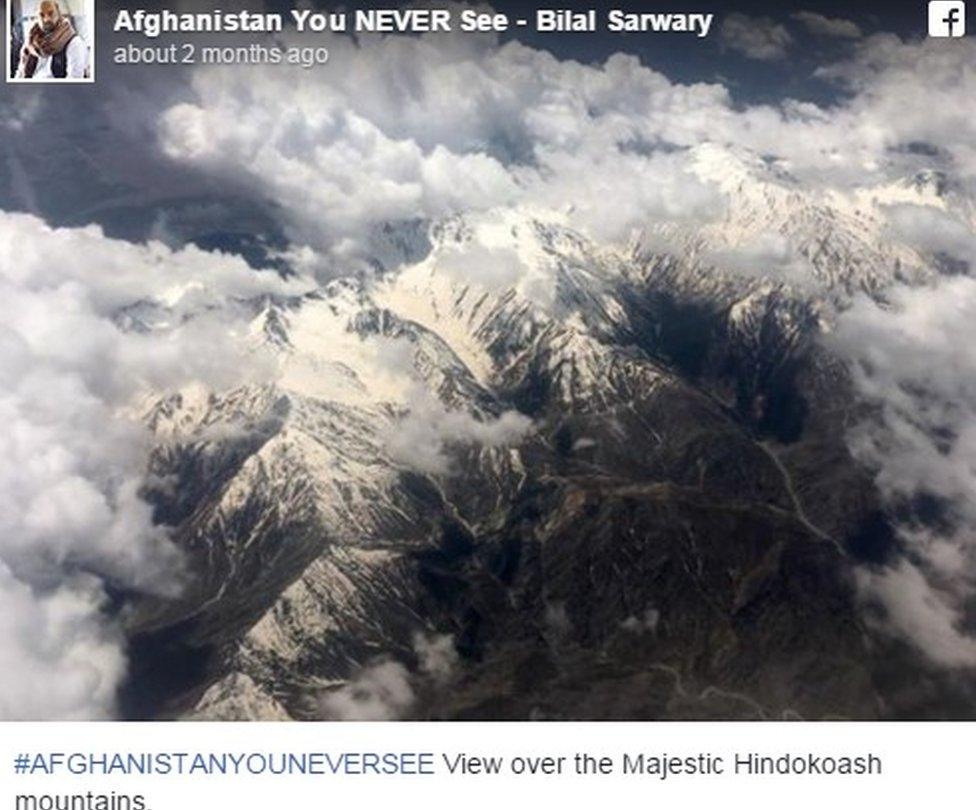

Huge areas of Afghanistan are no-go areas for visitors, said Bilal Sarwary, an Afghan journalist who does his part to promote the 'Afghanistan You Never See' on his Facebook page, external, but that is not to say everywhere is inaccessible.

"The State Department, the FCO, all advise it is not safe. It is not Sri Lanka or the Maldives, but it's not Libya or Syria either," he said.

"There are places in Afghanistan that are totally safe for tourists. If you fly into Kabul, then fly to Bamiyan or Herat, that's the safe way.

"What attracts people to Afghanistan is its diverse landscape - from mountains to deserts to lakes."

Bilal Sarwary's Facebook and Twitter feeds extol the virtues of the hidden Afghanistan

If you are visiting Afghanistan, Bilal's advice is to carry out plenty of research and avoid roads by flying to your destination.

"Most people I know who've been as tourists had a friend or family member who was an aid worker," he said. "It's not totally impossible."

The attack on the tourists, who were travelling with security forces, happened on a road between Ghor and Herat in the west of the country.

While Herat itself is seen as relatively safe, Bilal expressed his surprise that tourists were travelling on that particular road.

The BBC's chief international correspondent, Lyse Doucet, who has been travelling to Afghanistan since 1988, said: "There are areas unaffected by the Taliban where you can enjoy Afghans' hospitality, kindness and gentleness, see beautiful sights and stay in decent hotels."

A waterfall on the edge of a dam in the Band-e-Amir National Park, Afghanistan's first

Eid al-Fitr was celebrated at the Jamee (mosque) in Herat

The risk, Lyse said, was not necessarily being in any one place, but in travelling between safe places.

"You can't say that any whole country is unsafe," she said. "But that's where local knowledge comes in.

"Even if you are going on a trip to Italy, you get the best advice - well you have to ask the same questions in Afghanistan, but you need to ask them in a much more comprehensive way to make sure the sources of your knowledge are good."

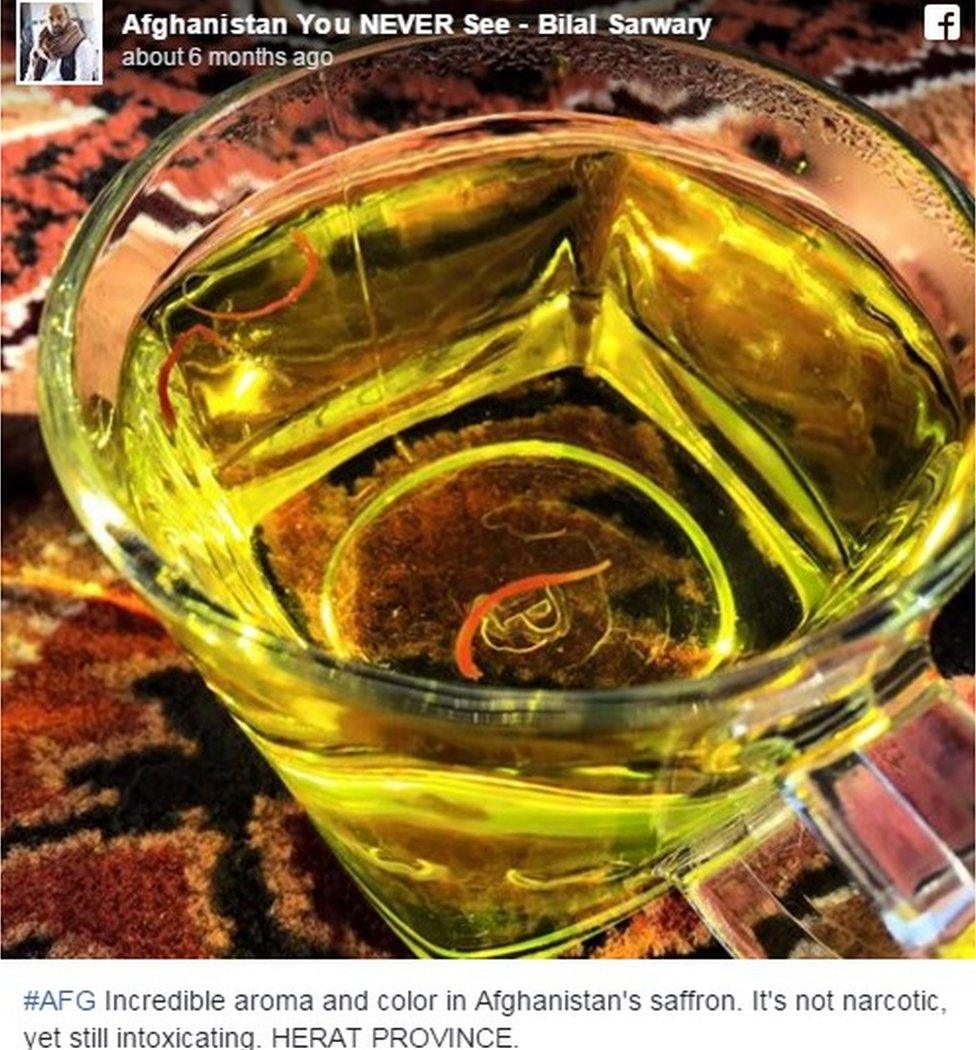

Afghan workers carry saffron flowers in Herat

The attack comes at a time when Herat, a city once occupied by Alexander the Great in 330BC, is seeking to capitalise on its relatively safe image to bring in more tourists.

"It's a country that's so cut off from the rest of the world when it comes to trade and tourism," Lyse said.

"So for those Afghans who want to see a better future, it's really depressing and demoralising, because every time they take a step up, they have to take a step back down."

Muqim Jamshady, of Afghan Logistics and Tours, is one of those taking another step back. "I'm really sad," he said. "And angry."

- Published4 August 2016

- Published13 August 2012

- Published30 July 2015