Nepal's sense of despair

- Published

More than a year after a devastating earthquake hit Nepal, many of its victims are still living in appalling conditions.

The Chuchepati camp is dotted with scores of shacks built with bamboo poles and white polythene and tarpaulin sheets.

It was set up for those displaced by the devastating earthquake in Nepal in April and May 2015.

I had to jump and sidestep the slush and sewage to reach the centre of the camp.

The stagnating puddles of water appeared to be a breeding ground for mosquitoes.

Standing outside a shack, Laxmi Nepali narrated her story with a wry look while comforting her seven-month-old son.

Her life has gone from bad to worse since the quake flattened her small mud and brick house in a village in the district of Sindhuli.

She is among hundreds of displaced people still living in this makeshift camp without running water, electricity, drainage or proper food.

The 30-year-old single mother broke into to tears as she described her daily struggle to feed her three children.

"We lost everything in the earthquake," she said.

"A few months ago, my husband also left me for another woman.

"We are not getting any help from the government.

"How can I manage with my three children?"

Her father, who works as a day labourer, gives her some support.

Ms Nepali's misery continues as the government and the aid agencies still wrangle over how to distribute aid to those affected by the quake.

It is estimated that more than 9,000 people were killed in the earthquake.

Nearly a million homes were destroyed or damaged in the country's worst ever disaster.

Hundreds of thousands of Nepalis are still living in temporary shelters dotted across the country.

A few metres away from Ms Nepali's hut, I met Susmita Thapa, who is visually impaired.

Ms Thapa, is originally from Sindhupalchowk district and lives with six of her family members in the camp.

Life was miserable in the camp, she said, adding that they wanted to return home.

Hundreds of thousands of Nepalis are still living in temporary shelters dotted across the country

"The government says it will give $2,000 [£1,540] to rebuild our houses," she said.

"How can we build our house with that money?

"It will cost three or four times more.

"My parents are day labourers, and we cannot afford it."

Nepal's chronic political instability, incompetence, corruption, convoluted bureaucracy of aid agencies and a crippling economic blockade from neighbouring India are often cited as reasons why people such as Ms Nepali and Ms Thapa are still living in camps in appalling conditions even 14 months after the disastrous earthquake.

Sushil Gyawali, chief executive of Nepal's Reconstruction Authority, accepts displaced people are facing difficulties.

But he said the reconstruction work was on track and the money being distributed to rebuild damaged houses.

"In addition to the $2,000 as grant, we have also announced that we are providing an additional $3,000 as interest-free loan," Mr Gyawali told me.

"People have started to receive the housing grant."

At the same time, he added, the government could provide only partial assistance and was not in a position to provide everything people had lost in the quake.

Just a few metres away from the camp, Kathmandu was bustling with activity.

Traffic jams are normal, and people have learned to live with them.

I could see Nepalese men and women wearing their masks to protect from dust pollution.

The roadside temples were full of worshippers.

But there was a sense of despair and helplessness among the people.

Many Nepalis said they were shocked by the attitude of neighbouring India, which shares close cultural, ethnic and religious links and an open 1,800km (1,100-mile) border.

As a landlocked nation, Nepal depends on imports from India for everything - from oil to pulses.

Nepal's ethnic Madhesi groups in the southern plains, bordering India, launched a general strike late last year in protest at the country's new constitution.

The people of Terai region share close cultural and family ties with people across the border in India.

The Madhesi groups were demanding better representation under the new constitution.

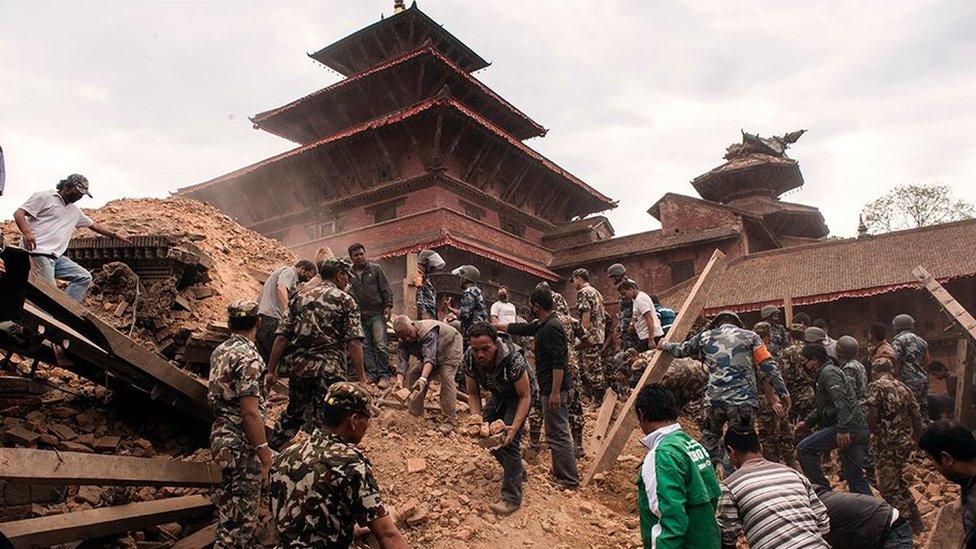

The April 2015 earthquake in Nepal killed nearly 9,000 people and injured more than 21,000. Aftershocks were felt in May.

The roadblocks prevented lorries carrying goods from India from reaching Nepal's hills.

Dozens of people were killed in clashes between protesters and security forces.

Some senior Indian officials reprimanded Nepali politicians for ignoring the demands of the Terai population.

Though the Indian government denied that it was behind the economic blockade, very few people in Nepal believed their denial.

The blockade, which lasted for nearly five months crippled life in Nepal.

There were long queues outside petrol stations, severe shortages of cooking gas and lifesaving medicines.

More importantly, Nepalese experts said the blockade had had a huge impact on earthquake reconstruction and rehabilitation, due to a lack of construction material.

An entire nation was seething with anger and despair.

"We felt very insulted and humiliated," Jamuna Gautam, an 18-year-old student, said.

"Our generation will not forget what we had experienced."

Finally, Nepal knocked at the doors of its northern neighbour - China.

But although Beijing offered some symbolic help, it could not translate into full fledged economic aid as difficult terrain in the Tibetan plateau prevented any large-scale movement of essential supplies.

Shortages caused by the blockade hampered efforts to recover from the earthquake

Nevertheless, the crisis made Nepalese politicians reconsider their relations with China.

"India has been myopic in its relations with Nepal," said veteran Nepalese analyst Yubaraj Ghimire.

"With one stroke the present Indian government has pushed Nepal into China's sphere of influence.

"The Chinese are coming into Nepal in a big way."

Nepalese politicians and media have long accused Delhi of meddling in the internal affairs of Nepal.

There is a strong sense here that Delhi micromanages events in Nepal.

The anti-Indian sentiment in Nepal is not new, but this time I could feel that it was deeply rooted.

The sentiment is somewhat similar in most countries in the region.

I was in Bangladesh a few weeks ago, and many were criticising India for meddling in their internal affairs.

From my days in Sri Lanka as a reporter, I could say how much both the Sinhalese and Tamils criticised India.

In Thimphu, many Bhutanese grudgingly accept India's overarching influence in the country.

Maybe India needs to reboot its relations with its immediate neighbours before reaching out to the outside world. But that is a different topic altogether.

After suffering ignominy for months, the Nepalese government finally held talks with India and the blockade was gradually lifted.

Analysts in Nepal say India was held in high esteem after it played a key role in bringing Nepal's various warring parties to the negotiating table in 2006, which brought an end to the country's decade-old civil war. But 10 years later, the story is totally different.

There is hope that the new Nepalese Prime Minister, Pushpa Kamal Dahal, better known as Prachanda (Nepali for "fierce one"), will work towards improving relations with India.

But many here feel that the trust Nepalese people had in India has vanished and the uneasy relationship with India is set to continue.

So, what next for Nepal?

"First, we have to bring our politics in our sovereign domain," said Mr Ghimire.

"Then, we have to make interdependence with any country - neighbouring or far away - dignified, and then we have to learn to live in crisis."