The surreal investigations into Thailand's unresolved bombings

- Published

Security has been stepped up at Erawan shrine in the wake of the recent attacks elsewhere in Thailand

If the investigation of last week's multiple bomb attacks in southern Thailand follows the pattern of that into the bombing of the Erawan Shine in Bangkok exactly a year ago, we are in for a surreal ride.

What we may not see is any convincing explanation for what happened.

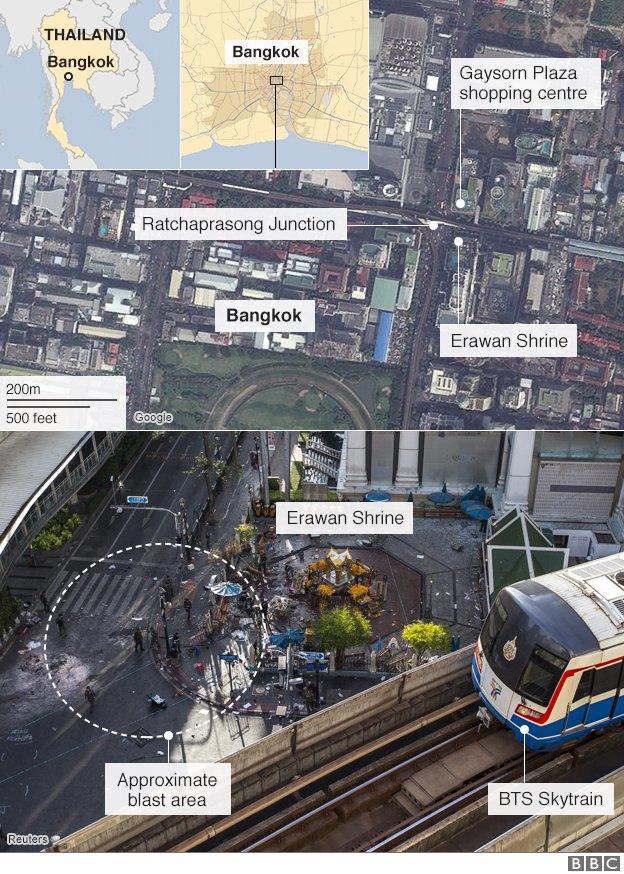

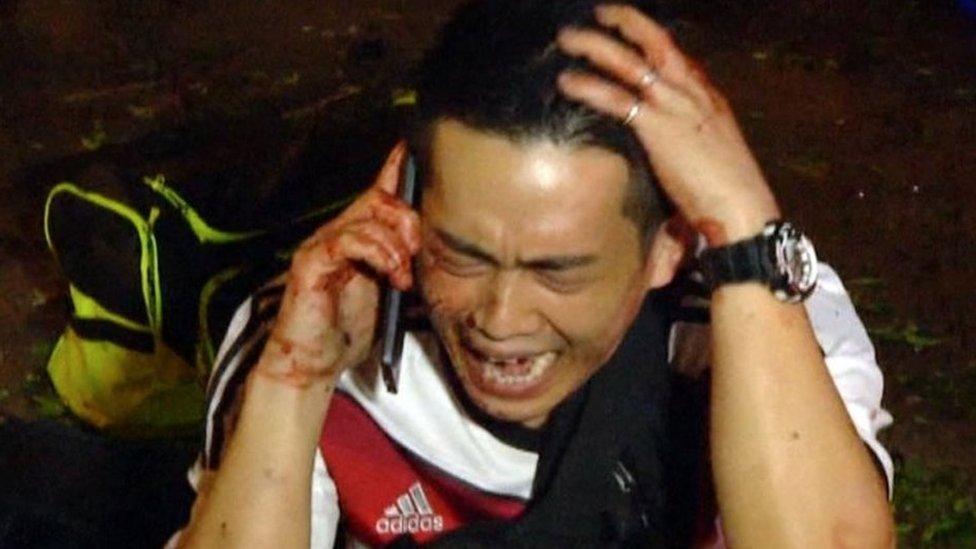

Like the spate of small bombs last week, the attack in Bangkok on 17 August last year was something new. Never before had such a large, deadly device been detonated at a symbolically-powerful location popular with foreign tourists. Twenty people died, and more than 120 were injured.

The immediate response of the military authorities was to deny any possibility that this was a terrorist attack. The next response was to deny any possibility that it might be retribution for a controversial decision a month before to deport 109 Muslim Uighur asylum-seekers back to China, where they faced harsh treatment as suspected insurgents. This despite the fact that the shrine was known to be popular with Chinese tourists.

Instead military spokesmen dropped heavy hints that their domestic political opponents - supporters of ousted Prime Ministers Thaksin and Yingluck Shinawatra - were to blame.

Even when two suspects were caught, both of them ethnic Uighurs, the Thai authorities initially refused to confirm their Chinese nationality, and insisted they were merely part of a people-smuggling gang frustrated over police operations constricting their business.

This official view has remained unchanged to this day, notwithstanding the discovery of large quantities of bomb-making materials in the same apartment where Bilal Mohammed, the first suspect, was apprehended.

It is still not entirely clear who was behind the Bangkok shrine blasts

But the police continued to try to link the attack with the opposition red-shirt movement. They stated last September that one of the key suspects was a known red-shirt activist, appropriately named Mr Odd, with links to a woman who was among 15 people believed to have fled to Turkey in the wake of the bombing. His photograph was circulated, but then the police appeared to lose all interest in him.

Neither did they make any visible efforts to get the 15 other suspects extradited from Turkey, despite the fact that one of them, a Uighur man named Abudustar Abdulrahman, who had flown out of Bangkok the night before the bomb, was believed to have played a central role in organising the attack.

Meanwhile the police put on a bizarre spectacle, awarding themselves a large pile of cash, equivalent to around $80,000, which had been raised as a reward for information leading to convictions.

The two detained suspects have since been indicted and held in a military base, with very few people allowed access to them.

Bilal Mohammed has been charged with placing the bomb under a seat in the shrine - the man caught on security camera videos that night - even though he looks quite different, and police had at first insisted he was not the man in the video. He has denied the charge and has written a letter insisting he was only trying to reach Turkey, using people-smugglers in Thailand.

Both men are being tried in a military court. The only translator found in Bangkok who can speak their language has since been arrested for drug offences, so they now have no way to follow court proceedings.

Both men have pleaded not guilty, and have hinted that they have been abused in custody. Bilal Mohammed broke down in tears on his way to court in May and shouted that he was "not an animal".

Their lawyer has advised that their best option is to plead guilty and hope for leniency.

Immediately after last week's bombings, the military authorities again suggested the most likely culprits were "those who have lost power", the same phrase used last year to point at the red-shirt opposition.

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha pointedly asked why the bombings had taken place right after the military had succeeded in getting its constitution - opposed by the red-shirts - approved in a national referendum.

Any thought that the attacks could be considered terrorism was once again dismissed. They were, said a police commander, just "domestic sabotage".

Tourist hotspots - including the royal resort of Hua Hin - were targeted in the latest attacks

Any possible link to the long-running separatist insurgency in Thailand's southern-most provinces was likewise dismissed, although those familiar with that conflict believe this is the most likely scenario. More recent comments by the military authorities are starting to acknowledge that possibility, and in his latest remarks the prime minister has said the government is not accusing any group.

Why does the military obfuscate the investigation of such critical events with so many baffling statements?

One obvious factor is the fear that tourism will be adversely affected if there is any suggestion of terrorism. Estimates vary, but tourism accounts for between 9% and 20% of the economy (depending on whether direct or indirect contributions are counted), and it is just about the only part of the economy which is growing.

Big terrorist incidents, like the Bali bomb in 2002, and more recent attacks in Turkey, do drive foreigners away. But the Bangkok bomb last year had only a brief impact, and provided there are no further attacks, the effect this time will probably also be limited.

Another factor is the embarrassment of such attacks to a military government that seized power in the name of restoring peace and order.

The latest attacks took place on the 84th birthday of Queen Sirikit, an auspicious anniversary for Thais and one the ultra-royalist military had wanted celebrated openly across the country.

In Hua Hin, the favourite residence of the royal family outside Bangkok, and the site of one of the attacks - the celebration had to be held inside a military barracks.

And acknowledging that the southern militants may be involved would underscore the military's failure even to contain, let alone resolve, a conflict which has cost more than 6,000 lives.

The experience of previous violent events in Thailand is not encouraging. Very few have ever been fully investigated.

The massacre of students in Bangkok in 1976; of pro-democracy protesters in 1992; the killing of more than 90 people during an occupation of Bangkok by the red-shirt movement in 2010, and the subsequent military operation against it; and the deaths of 30 people in the rival yellow-shirt occupation of 2013-2014 before the coup - details of all these events remain disputed, their causes unexplained, and most of the perpetrators unpunished.

No-one should be surprised if the bombings, last year and this year, produce a similar outcome.

- Published12 August 2016

- Published19 February 2013

- Published12 August 2016

- Published16 February 2016

- Published19 August 2015

- Published19 August 2015

- Published18 August 2015

- Published17 August 2015

- Published16 August 2024