Myanmar's Rohingya Muslims: Glimmer of hope at last?

- Published

Many Rohingya still live in camps after waves of communal violence in 2012

There haven't been many good moments for Myanmar's Rohingya Muslims in the last four years.

This country's dramatic political changes have passed them by. Greater democracy has not brought greater respect for the stateless Rohingya's human rights.

But the formation of an Advisory Commission on Rakhine State represents a rare glimmer of hope.

For the first time, the Burmese government is seeking international expertise to try and solve one of the country's most complex problems.

It's a significant shift. For years, the official Burmese mantra has been that "no foreigner can possibly understand Rakhine's problems".

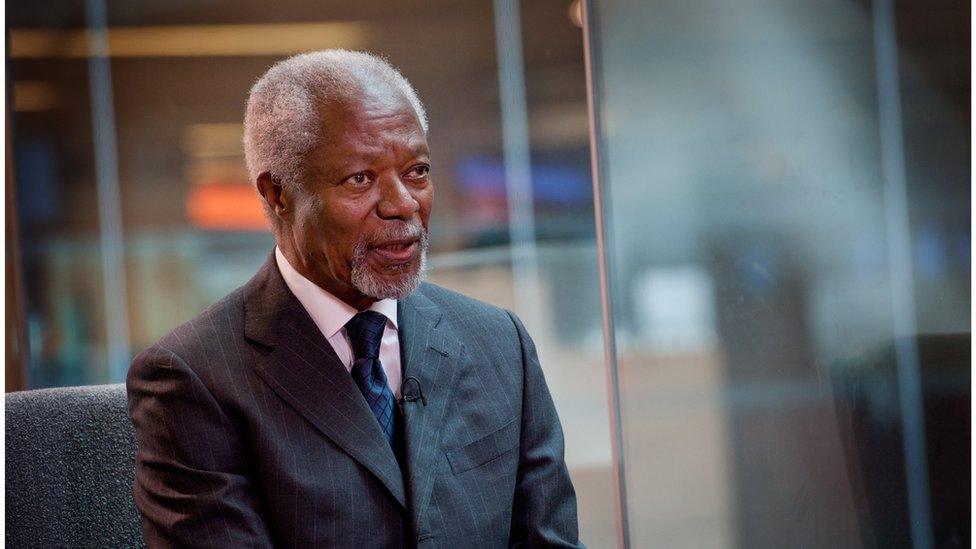

Now Kofi Annan, the former UN secretary general, has been tasked with taking a fresh look at the issues as head of nine-member commission. His report could just add to the mountain of papers written about Rakhine and the Rohingya, or it just might be a game-changer.

Many Rohingya have been driven to take dangerous journeys at sea in pursuit of a better life elsewhere

So what's Aung San Suu Kyi up to?

Well, first a cynical take. Next week the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon is due in the Burmese capital Nay Pyi Taw and in September Ms Suu Kyi will head to the United States for the UN General Assembly and talks with President Obama.

The Nobel laureate was no doubt bracing herself for awkward questions about why she wasn't doing more to help Myanmar's Muslim minority and in particular the 800,000 or so Rohingya. Those questions can now be easily deflected with reference to this new commission.

But there's more at play than that. By setting up the commission, Ms Suu Kyi is signalling that she is open to new ideas, and doesn't have all the answers.

Kofi Annan may be 78 but, as you'd expect from a former UN secretary general, he's his own man.

The appointment of Kofi Annan as head of the commission may help deflect criticism

The final report, due to be delivered by the end of August 2017, is likely to contain suggestions that many Burmese consider unpalatable.

Almost certainly it will insist that the Rohingya's basic human rights are respected, perhaps recommending that Myanmar offer them a better route to citizenship.

In Myanmar's current political climate it's hard for Ms Suu Kyi to bring those ideas to the table. She'd be attacked not just by hardline Buddhists but many within her own party.

So Kofi Annan and his report could be the "Trojan Horse" that brings this sort of proposal into the national debate.

There are of course plenty of caveats.

Problems as deeply entrenched as those between the Buddhist and Muslim communities in Rakhine State will not be solved overnight. The animosity between them has built up over decades with many in the Buddhist majority seeing the Rohingya as illegal immigrants from across the border in Bangladesh.

Some have criticised Aung San Suu Kyi - a human rights champion - for her silence on the plight of the Rohingya

After the violence of 2012, more than 100,000 Rohingya were forced from their homes into camps. In the years that have followed there's been no real effort to help them return.

Rakhine has become increasingly segregated, with some comparing it to South Africa's apartheid. Things have become quieter but there's been little reconciliation.

Whatever the commission ends up concluding, any move to give the Rohingya greater rights will be hugely controversial not just in Rakhine State but across the country.

Vocal parts of the Buddhist community are openly hostile towards international aid agencies and the UN. They're unlikely to welcome Kofi Annan's team, no doubt anticipating the sort of recommendations he might make.

Implementing any "solution" will be even harder.

But the formation of this advisory commission is something new. However small, it's the first bit of positive news that the Rohingya have had for a long time.

- Published22 May 2016

- Published6 November 2015

- Published20 May 2015

- Published10 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published18 May 2015