The Saddam factor in North Korea's nuclear strategy

- Published

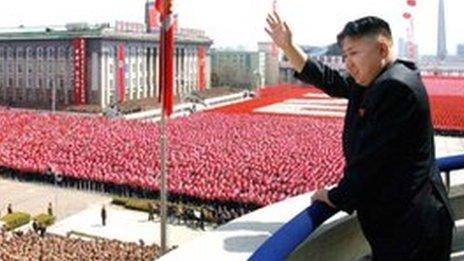

Kim Jong-un may believe nuclear weapons protect him from assassination

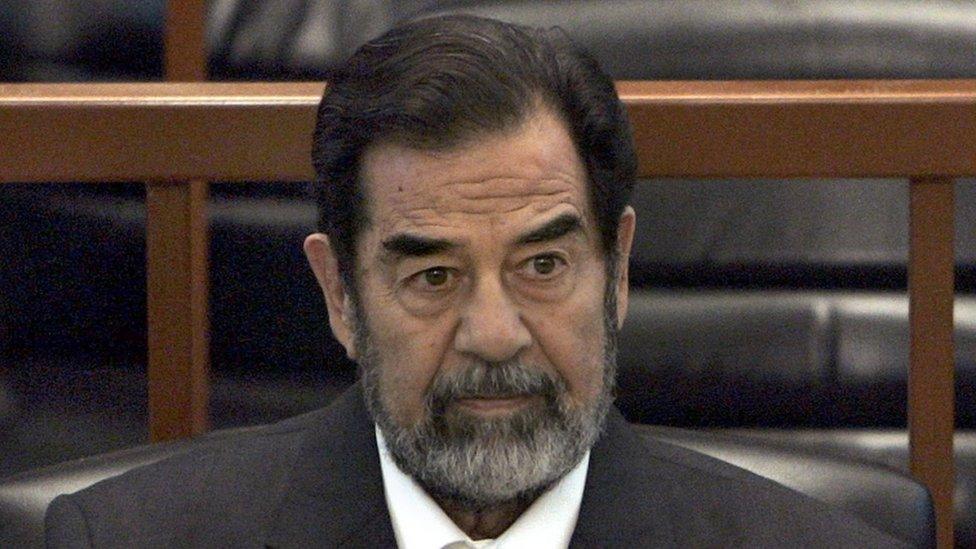

Might Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi explain Kim Jong-un's determination to get his own nuclear arsenal?

The lynching of the Libyan leader after he had renounced nuclear weapons and the hanging of the Iraqi president have been cited by the North Korean media as the rationale for their own country's determination not to be put off by sanctions despite the poverty there.

As it is sometimes put: Gaddafi gave up the bomb and lost his head. Saddam was toppled because he did not have it.

After Pyongyang's last nuclear test in January, a commentary in North Korea's media said: "History proves that powerful nuclear deterrence serves as the strongest treasured sword for frustrating outsiders' aggression."

It continued: "The Saddam Hussein regime in Iraq and the Gaddafi regime in Libya could not escape the fate of destruction after being deprived of their foundations for nuclear development and giving up nuclear programmes of their own accord."

Hatchet-faced

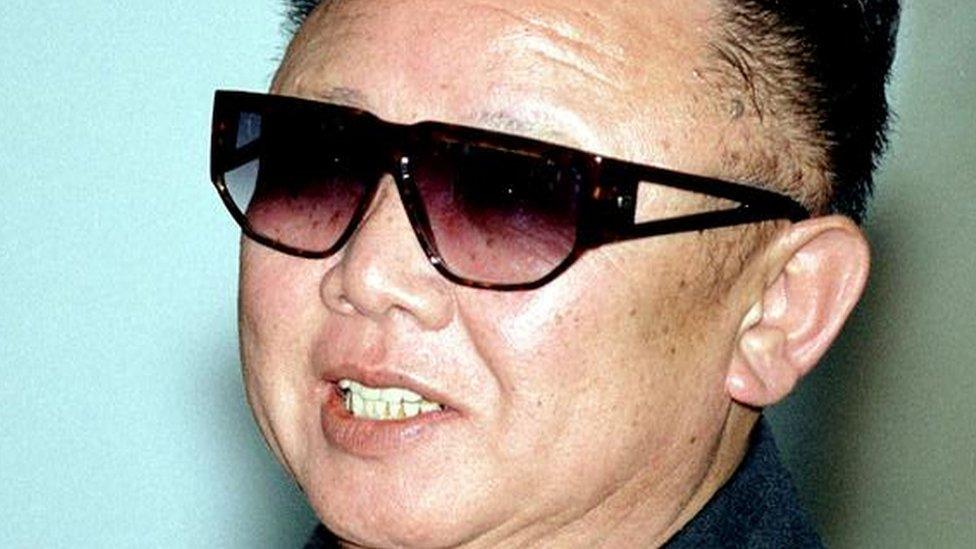

Kim Jong-un, like his father Kim Jong-il, must know that the possession of nuclear weapons gives a country clout.

It is hard to imagine the atmosphere in the supreme leader's compound. It is a regime of purges and executions and it might resemble a mediaeval court where those at the top perpetually fear plotters.

Saddam Hussein had no nuclear weapons and was toppled, the argument goes

As the saying goes: just because you're paranoid doesn't mean they're not out to get you.

It is not known whether US or South Korean special forces have plans to "behead" the regime by killing its leader. But it was certainly reported in the South Korean media this year that such plans existed - and if South Korean papers are saying so - true or false - North Koreans might believe it.

Certainly, wherever Kim Jong-un travels, there is the most intense security. Buildings in which he speaks are surrounded by stern security guards, standing in line, spaced about 10 metres from each other on the circumference of the building, all identically dressed in dark suits with bulges indicating weapons.

They are hatchet-faced and tough. Western journalists are repeatedly searched to make sure they do not have GPS devices which could locate the position of the leader.

During the last Gulf War in 2003, Kim Jong-un's father and predecessor as leader disappeared from public view for 44 days. It was surmised at the time that Kim Jong-il feared assassination by Tomahawk missile.

If Kim Jong-un has his own finger on the nuclear button, that calculation changes. His fear that the United States or South Korea might kill him suddenly is diminished.

That may be his personal fear but nuclear weapons would also give the country itself more clout.

'Credible substitute'

North Korea may believe it has good reason to fear the United States. Kim Il-sung - Kim Jong-un's grandfather - allied himself with both the Chinese Communist Party and the Soviet Union.

He took power in the north after the civil war ended in the divided peninsula with the United States still garrisoned in the south - as it is today.

When the world was divided between communism and the West led by the United States, Kim Jong-un was on the other side. Old enmities die hard.

Kim Jong-il reportedly disappeared during the 2003 Gulf War to avoid assassination

Prof John Delury, of the Yonsei University Graduate School of International Studies, told the BBC: "Above all else, North Korea's nuclear programme is about security - it is, by their estimation, the only reliable guarantee of the country's basic sovereignty, of the Communist regime's control, and of the rule of Kim Jong-un.

"North Korea learned from Iraq that Saddam Hussein's mistake was he did not possess the weapons of mass destruction he was falsely accused of having. Libya taught a similar lesson.

"So, until we can help Pyongyang find a credible substitute to guarantee its security, and give Kim Jong-un the kind of prestige that comes with being a member of the nuclear club, then we can expect more tests, more progress and more 'provocations'."

But can the outside world help Pyongyang find a credible substitute which would guarantee security?

Until 2009 North Korea was, on the face of it, prepared to negotiate. From 2003, it had taken part in the "six-party talks" also involving China, the United States, South Korea, Japan and Russia.

But the process was always disjointed, as North Korea launched missiles. In 2009, Pyongyang walked out. A year later, a visiting American scientist was stunned to be shown a room full of centrifuges used for enriching uranium, the necessary ingredient for the bomb.

After this latest test, China called for a resumption of the six-party talks. It is unlikely to happen.

Under Kim Jong-un, what the South sees as provocative gestures have increased compared with his father's era. The North Korean military fires missiles every 10 days or so at the moment, contrary to UN resolutions.

It may be a measure of his back-to-the-wall defiance as his nuclear ambitions have progressed and sanctions have tightened.

And the current frequency of nuclear testing - one in January and one now - indicates a rush to get the necessary weapons technology, experts say.

Kim Jong-un is bent on his nuclear arsenal. It is hard to see what could dissuade him.

- Published9 September 2016

- Published9 September 2016

- Published10 August 2017

- Published3 September 2017

- Published18 April 2016

- Published9 September 2016

- Published10 December 2015