North Korea: When is an earthquake a nuclear test?

- Published

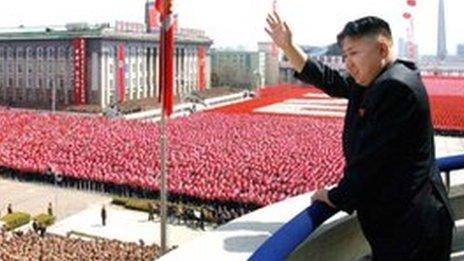

A huge rally was held in Pyongyang days after North Korea claimed its fifth successful test this year

The first sign that North Korea had carried out its fifth nuclear test last month was when a massive earthquake was detected by international scientists. As North Korea marks 10 years since its first test, geophysicist and disaster researcher Mika McKinnon explains how scientists have learned to identify these world-shaking events.

Weapons tests cannot hide from science.

Every stage of North Korea's nuclear weapons development programme is under global observation, with scientists using data to extract the true state of their progress.

A worldwide network of sensors is constantly collecting data, seeking the faintest rumble of a weapons test.

When one takes place, the explosion slams into its surroundings.

The vibrations propagate through water, air, and earth, too low frequency to be heard by human ears but picked up by sensors and relayed to control centres for analysis.

A disturbing pattern

On 9 October 2006,, external seismometers around the world lit up, detecting a significant explosion in North Korea.

The infrasound network stayed silent, the lack of an atmospheric blast indicating it happened underground away from prying satellites. Yet more silence on underwater hydro acoustic stations confirmed it had been muffled by rock, not water.

The scientist triangulated the direction and time of seismic waves to pinpoint the explosion's origin under mountains in North Korea.

All the signs suggested a nuclear test.

In the following days, monitoring stations sniffed the air looking for the faintest trace of radioactive isotopes.

If any isotopes escaped from the test tunnels to drift in the wind, they'd be unmistakable relics of radiation from a nuclear blast and rule out any chance of a conventional weapon.

Two weeks later, a radionuclide station in Yellowknife, Canada downwind of the North Korea test site picked up elevated levels of Xenon 133, a radioactive product of nuclear fission.

The data was processed at the International Data Centre in Vienna, headquarters for the Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), confirming a nuclear weapons test.

This disturbing pattern of an earthquake followed by North Korea confirmation of a nuclear test was repeated in May 2009, February 2013, January 2016, and most recently on 9 September this year.

Each time, scientists knew the test has happened before North Korea formally confirmed them.

And each burst of energy from North Korea has been larger than the one before, with the Norwegian monitoring station Norstar calculating that the most recent test indicated an explosive yield of approximately 20 kilotons of TNT.

How do scientists know what blast is what?

The backbone of this monitoring programme are seismometers, extremely sensitive microphones attuned to the Earth's quivers.

Everything from a catastrophic earthquake to a passing truck has a distinct vibration.

Earthquakes start with a quick, sharp pressure wave followed by the more destructive shear and surface waves that shake buildings from their foundations. Landslides are a drawn-out jumble of debris rolling down slopes, and volcanic eruptions can be spotted with the sudden blast of a breaking rock propelled by lava and gas.

Seismometers near beaches pick up a regular surge of seismic signals, a gentle steady beat generated by waves crashing on sand every moment of every day.

Explosions, too, have their own unique signature, a blast of high-intensity chaotic seismic energy confined to a brief duration.

Scientists first realised this during the Cold War, with the United States funding research into seismology to remotely track progress of the Soviet Union's weapons development programme.

Before long, scientists worldwide collaborated to create standards for measuring seismic energy and to share their observations, progressing our understanding of earthquakes along with their more sombre monitoring task.

North Korea's leader Kim Jong-un and state media have made claims of nuclear advancement that remain unverified

This information-sharing of the 1960s was the kernel that evolved into today's global network of science stations that verify nations obey the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

Every nation has its own seismic network, but the CTBTO runs an independent network of strategically spread stations around the world for independent, consistent monitoring.

Every day, seismic stations pick up the blasts from mining operations, seismic surveys, or military exercises.

The explosions are identified by their small size and location, dismissed from concerns of clandestine weapons tests unless the radionuclide stations find unexpected gases.

Many more signals are mundane in nature - the daily noises of people crawling all over this busy planet. Busy highways with roaring trucks and clattering trains on regular schedules are common sources of seismic noise.

Even heavy footfalls of hikers exploring the paths used to service seismic stations are all picked up, recorded as small regular hiccups in the seismograph.

Seismic activity can't always be attributed to sinister causes

Once, a team of scientists monitoring a seismic feed were concerned by a sudden localised signal at a station on Vancouver Island in Canada. Fearful someone was attempting to vandalise their equipment, the scientists checked on the seismometer only to discover a pair of teenagers using the encasing protective vault to get better acquainted.

The discovery shed light on other signals detected by seismometers in scenic, secluded, yet accessible settings, the rhythmic peaks of waxing and waning energy finally tied to a specific activity.

Once identified, carefully serious scientists were able to recognise it at other locations, spotting unexpected Lover's Lanes twisting through remote seismic stations.

Not every seismic detection tells a horrifying story, but just rarely they pick up something special, something big, intense, and scary: a nuclear test.

Mika McKinnon is a US-based geophysicist and disaster researcher. Follow her on Twitter: @Mika McKinnon, external

- Published10 August 2017

- Published3 September 2017

- Published11 September 2023