Drugs, money and wildlife in Myanmar's most secret state

- Published

Wa's border is not one that journalists are often invited to cross

The remote Wa region of Shan state in Myanmar's east is a place few outsiders have seen. The people who live in this unofficial, effectively autonomous state within Myanmar used to be called the Wild Wa, and as the BBC's Jonah Fisher found, drugs, money and the wildlife trade are flourishing.

Wa state is one of the most secretive places on earth. Search for it on Google Maps and you won't find it. Ask for a visa and you'll be denied.

"We thought everyone who wanted to visit were spies," one Wa official said.

But times in Myanmar, and in Wa state, are changing.

So for reasons that are still not entirely clear, the BBC was among a small group of international and local journalists invited for a first ever guided tour.

Our entry was via a border post not far from Myanmar's north-eastern border with China.

Rare animal parts traded openly in Myanmar's Wa region

Having been thoroughly checked out by Burmese soldiers, we cross no-man's land and are warmly embraced by our minders from the local TV station, Wa TV.

"Welcome to Wa state," they beam at us as we are ushered into the back of waiting pickups. It is like a long awaited first date, and given the history of the Wa people we are just a little bit nervous.

Back in British colonial times they were known as the "Wild Wa", famous for fighting ferociously and chopping the heads of their enemies off, before displaying them on poles.

Awkward jokes about head-hunting out of the way, we travel south into rebel territory.

Wa state is about the size of Wales, with a population of about half-a-million. It is really a state within a state, hugging the Chinese border. Its autonomous status dates back to a peace deal Wa rebels struck with central government in 1989.

In return for stopping fighting, the rebels were given land to manage as they wished. So the Wa grew the most lucrative crop they could get their hands on - poppies.

Over the next decade, Wa state and the Golden Triangle cemented its reputation as one of the world's leading producers of opium and heroin.

Built partly with illicit money or not, Wa has schools and infrastructure the envy of some other Burmese states

The point of our carefully organised trip appears, at least in part, to show that the Wa have kicked their drug habit.

So in our first few days we're taken to see some of the crops that have replaced the poppies. Tea, coffee and rubber.

In Mong Mao, Wa's second town, a Taiwanese businessman comes to speak to us at the immaculately manicured oolong tea plantation he owns. He tells us that in common with almost everything that is made in Wa state, all his tea is sold to China.

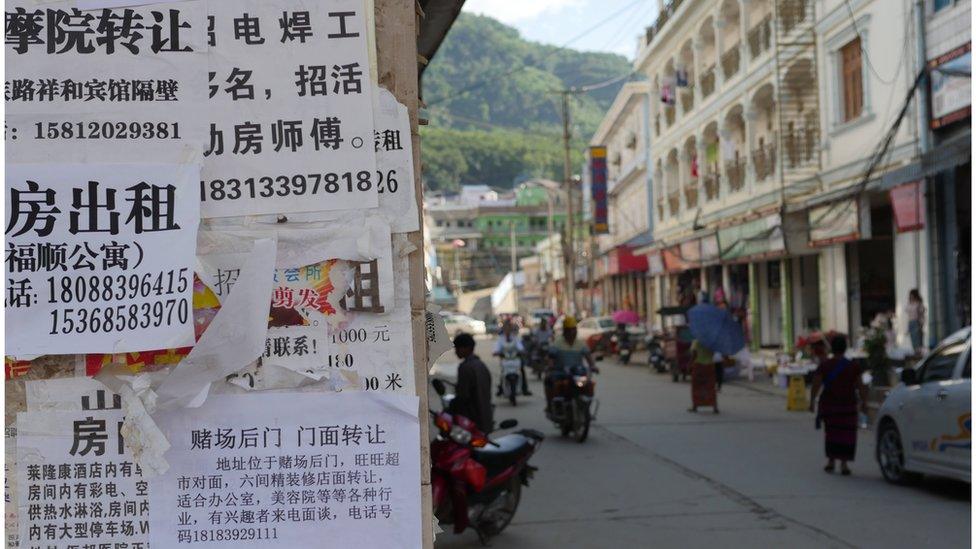

In fact, Wa state feels more like China than Myanmar. The money used is the Chinese yuan, the main language Mandarin, and infrastructure, like electricity and mobile phone networks, comes over the border from Chinese companies.

Much of the state's business, including tea production, is with China

"I don't know what we get from being part of Myanmar", Construction Minister Yeng Gar tells us with a loud laugh. "But we don't want independence, we do want to be part of Myanmar."

It is a strategy that's worked well. The Wa have spent the last two decades astutely playing their two large neighbours off against each other.

A well equipped rebel army keeps the Burmese military at arm's length, while close business ties with China have allowed the Wa to build infrastructure and prosper. We are shown roads and schools that would be the envy of other, more "loyal" Burmese states.

But drugs are still a major issue. From what we can see, large-scale opium production has ceased, but the drug habit may have simply gone indoors.

United Nations and US State Department reports accuse the Wa of becoming major manufacturers of methamphetamine pills, known locally as "yaba".

The currency, language and infrastructure in Wa is mostly Chinese

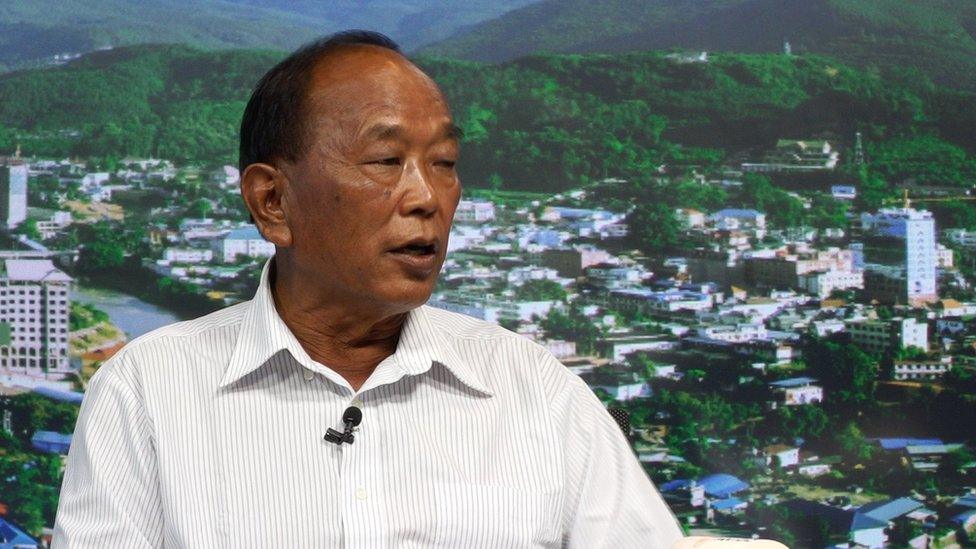

Disappointingly, meth factories don't feature on our itinerary. But we do persuade our minders to let us speak to Justice Secretary Li San Lu.

He is surprisingly candid, telling us that meth production is a huge problem, with two tonnes of pills having been seized this year alone. The blame, he says, lies with outsiders.

"We locals don't know how to make yaba," he says somewhat implausibly. "The ingredients are all being brought in from China, India and Thailand and then manufactured here. We're the victims."

Before we could press him any further our minders stepped in and informed us that our reporting was over for the day.

That night, feeling mutinous, we skipped the karaoke, side-stepped the minders and headed out for an unguided look around Panghsan, the state capital.

Unlike in many wildlife markets, in Wa the products are sold in upscale shops

It was soon clear that the Wa's taste for the illicit isn't limited to drugs.

On almost every street was a shop selling the parts of endangered animals.

Tiger teeth and skulls, elephant tusks and pangolin skins were all openly on sale. The women behind the counter tell us that most of their customers are Chinese and that delivery across the border can easily be arranged.

The state's foreign minister explained that wildlife products on sale there weren't from Wa as it had long ago cut down much of its jungle

Myanmar's most famous wildlife market, Mong La, is just 100km (62 miles) away, but what is striking about Panghsan is how organised and high-end it is.

These shops are not market stalls, but supermarkets of endangered animals' parts. A previously undocumented gateway into the lucrative Chinese market.

We film the shops discreetly with our mobile phones before showing the footage to Nick Cox from the World Wildlife Fund when we return to Yangon.

"It shows that there are more markets than we were previously aware of," he says. "To see a market with such high-end stores selling highly finished products of critically endangered species show this problem isn't going anywhere.

"There is still a massive demand and people have a lot of money to spend on these products."

Lush, green and hilly, Wa state is about the same size as Wales

The Wa, for their part, do not see stopping the trade in animal parts as their problem.

"We don't have those sort of animals here, we cut down all our jungle for rubber plantations," Foreign Minister Zhao Guo An says. "This is just free trade."

And that, to a certain extent sums up the Wa. Detached from both national and international laws, they do exactly as they please. And they do not want to change.

Efforts to pull them into plans for a new more federal Myanmar have to date been a complete failure. Having been forced by the Chinese to attend talks, the Wa delegation walked out in a huff on day one, when they were given the wrong accreditation badges.

The message was clear. The Wa are happy with the status quo and the freedom that comes with it.

- Published31 August 2016

- Published15 October 2015

- Published28 January 2016

- Published18 August 2014

- Published6 January 2014

- Published13 July 2013