Myanmar ethnic groups attend government peace talks

- Published

The government and military in Myanmar are holding landmark peace talks with armed ethnic groups as part of efforts to bring an end to decades of conflict.

The meeting in the capital Nay Pyi Taw, involving 17 groups, is being opened by Aung San Suu Kyi and attended by UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon.

Negotiations on a permanent peace are expected to last months if not years.

But opening the five-day talks, Aung San Suu Kyi said unity was essential for Myanmar's future.

"So long as we are unable to achieve national reconciliation and national unity, we will never be able to establish a sustainable and durable peaceful union," she told attendees.

"Only if our country is at peace will we be able to stand on an equal footing with the other countries in our region and across the world."

Mr Ban has said the talks are "an important first step".

Why are the talks happening now?

Myanmar, also known as Burma, has been plagued by violence since gaining independence in 1948, involving ethnic minority groups seeking independence or greater autonomy and angry at the dominance of the Burman ethnic majority.

The former military-backed government had reached truces with some groups, but has never managed to secure a nationwide deal. Sporadic violence has killed or displaced tens of thousands of people over the years.

Myanmar's de factor leader Aung San Suu Kyi has said securing peace is a priority for her National League for Democracy, which won elections last year.

Who is taking part?

All armed ethnic groups, which have tens of thousands of fighters between them, were invited and most are attending, along with representatives from the government, army, political parties and civil society.

They include the Karen, Kachin, Shan and Wa, all of which agreed to put down their weapons to attend.

But three smaller armed groups have not been invited, because they would not agree to the terms and are still fighting government forces.

What deal is likely to be reached?

The BBC's Jonah Fisher in Nay Pyi Taw says the armed groups have been brought to the table by vague promises of a more federal Myanmar with power and resource sharing.

But the military, which still holds 25% of seats in parliament, sees its role as resisting the break-up of Myanmar, so are likely to oppose any such move. It also remains unclear, he adds, how much devolution of power Suu Kyi actually wants.

For it's part the army would like the armed groups to begin disarming as soon as possible, and wants the 2008 constitution which it effectively drafted at the heart of any peace deal. The group would like to hold onto their arms until a deal is reached.

Our correspondent says the complexity and scale of the talks are daunting, but they are almost certainly Myanmar's best chance for nationwide peace in nearly 70 years.

Rohingya 'deserve hope'

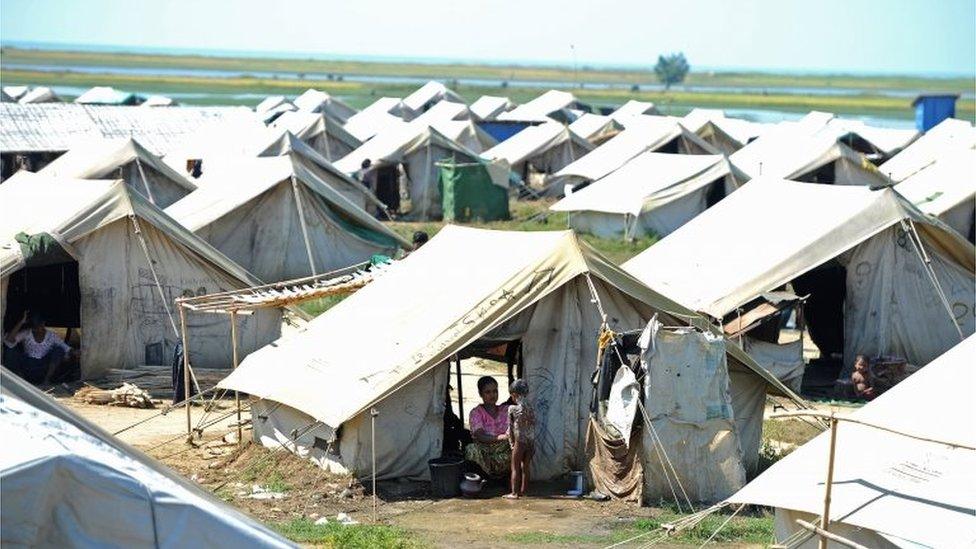

Tens of thousands of Rohingya are still displaced after communal violence

Mr Ban has also used his visit to Myanmar to raise concern on the separate issue of the plight of the Rohingya minority.

He said the marginalised Muslim ethnic group, who are not officially recognised by Myanmar, "deserve hope".

Tens of thousands of Rohingya are living in temporary camps in northern Rakhine state after being displaced by deadly communal violence in majority Buddhist Myanmar in 2012.

Mr Ban said the government has assured him it was addressing the Rohingya issue

The government, along with many Burmese, consider the Rohingya to be illegal Bangladeshi migrants. They are not formally recognised by law and have no voting rights.

Mr Ban told reporters on Tuesday the Myanmar government "has assured me about its commitment to address the roots of the problem".

He said the Rohingya "need and deserve a future, hope and dignity. This is not just a question of the Rohingya community's right to self-identity".

Last week, Ms Suu Kyi, who has been accused of ignoring the Rohingya, set up a commission to investigate the issue, led by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan.

- Published24 August 2016

- Published8 July 2016

- Published10 June 2015

- Published26 May 2023