Who will help Myanmar's Rohingya?

- Published

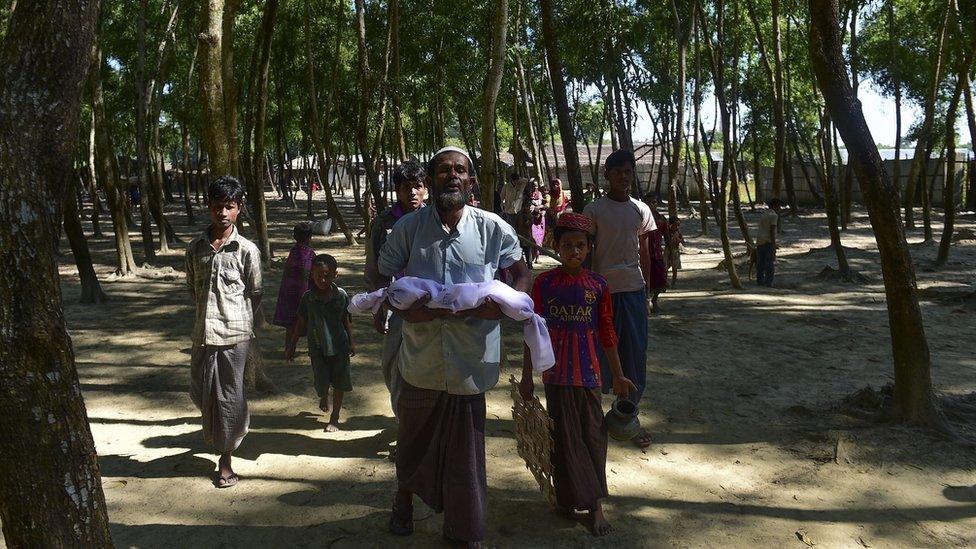

Tens of thousands of Rohingya have fled to refugee camps in Bangladesh since October

Rejected by the country they call home and unwanted by its neighbours, the Rohingya are impoverished, virtually stateless and have been fleeing Myanmar in droves and for decades.

In recent months, tens of thousands of Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh amid a military crackdown on insurgents in Myanmar's western Rakhine state.

They have told horrifying stories of rapes, killings and house burnings, which the government of Myanmar - formerly Burma - has claimed are "false" and "distorted".

Activists have condemned the lack of a firm international response. Some have described the situation as South East Asia's Srebrenica, referring to the July 1995 massacre of more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims who were meant to be under UN protection - a dark stain on Europe's human rights record.

What's happening?

Tun Khin, from the Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK, says Rohingyas are suffering "mass atrocities" perpetrated by security forces in the northern part of Rakhine state.

A counter-insurgency campaign was launched after nine border policemen near Maungdaw were killed in a militant attack in early October, but the Rohingya say they are being targeted indiscriminately.

'They set our houses and mosque on fire'

The BBC cannot visit the locked-down area to verify the claims and the Myanmar government has vociferously denied alleged abuses.

But UN officials have told the BBC that the Rohingya are being collectively punished for militant attacks, with the ultimate goal being ethnic cleansing.

What led to the current situation?

The Rohingya are one of Myanmar's many ethnic minorities and say they are descendants of Arab traders and other groups who have been in the region for generations.

But Myanmar's government denies them citizenship and sees them as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh - a common attitude among many Burmese.

The predominantly Buddhist country has a long history of communal mistrust, which was allowed to simmer, and was at times exploited, under decades of military rule.

Thousands of Rohingya have been forced to live in camps

About one million Muslim Rohingya are estimated to live in western Rakhine state, where they are a sizable minority. An outbreak of communal violence there in 2012 saw more than 100,000 people displaced, and tens of thousands of Rohingya remain in decrepit camps where travel is restricted.

Hundreds of thousands of undocumented Rohingya already live in Bangladesh, having fled there over many decades.

Where is Aung San Suu Kyi?

Since a dramatic Rohingya exodus from Myanmar in 2015, the political party of Nobel Peace Prize winner and democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi has taken power in a historic election, the first to be openly contested in 25 years.

But little has changed for the Rohingya and Ms Suu Kyi's failure to condemn the current violence is an outrage, say some observers.

"I'm not saying there are no difficulties,'' she told Singapore's Channel NewsAsia in December. "But it helps if people recognise the difficulty and are more focused on resolving these difficulties rather than exaggerating them so that everything seems worse than it really is.''

Her failure to defend the Rohingya is extremely disappointing, said Tun Khin, who for years had supported her democracy activism.

The question of whether she has much leverage over the military - which still wields great power and controls the most powerful ministries - is a separate one, he said.

"The point is that Aung San Suu Kyi is covering up this crime perpetrated by the military."

Aung San Suu Kyi mostly avoided the Rohingya question on a recent official visit to Singapore

But others say international media fail to understand the complex situation in Rakhine state, where Rohingya Muslims live alongside the mostly Buddhist Rakhine people, who are the state's dominant ethnic group.

Khin Mar Mar Kyi, a Myanmar researcher at Oxford University, told the South China Morning Post, external that the Rakhine were the "most marginalised minority" in Myanmar but were ignored by Western media, which she said displayed a "one-sided humanitarian passion".

Other researchers like Ronan Lee of Australia's Deakin University disagree with this argument, noting that while the Rakhine also face deprivation, "the solution when faced with massive rights violations is not to announce that someone else is worse off".

In her recent media comments, Ms Suu Kyi said Rakhine Buddhists "are worried about the fact that they are shrinking as a Rakhine population percentage-wise" and said she wanted to improve relations between the two communities.

A special Myanmar government committee appointed to investigate the ongoing violence in Rakhine state said in an interim report in early January that it had so far found no evidence to support claims of genocide against the Rohingya, nor to back up widespread rape allegations.

The report made no mention of claims that security forces had been killing civilians. Observers had, in any case, not had high hopes of a credible or independent investigation from the committee, which is headed by former general and current Vice-President Myint Swe.

Read more - "The Lady": A profile of Aung San Suu Kyi

Will Myanmar's neighbours help?

South East Asian countries generally don't criticise each other about their internal affairs. It's a key principle of the 10-member Association of South East Asian Nations (Asean).

But the current situation has seen some strident criticism from Myanmar's Muslim-majority neighbours, along with protests. Indonesian police even say they have foiled an IS-linked bomb plot targeting the Myanmar embassy.

On 4 December, Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak questioned Aung San Suu Kyi's Nobel Prize, given her inaction.

"The world cannot sit by and watch genocide taking place. The world cannot just say 'look, it is not our problem'. It is our problem," he told thousands at a rally in Kuala Lumpur in support of the Rohingya.

His comments followed a call from Malaysia's youth and sports minister, Khairy Jamaluddin, for Asean to review Myanmar's membership over the "unacceptable" violence.

Some question the timing of the comments, given the unpopular Mr Razak is gearing up for re-election.

"What we want is both talk and action to really help the Rohingya, not just ministers posturing to gain domestic political points," said Phil Robertson of Human Rights Watch.

In Bangladesh, which borders Rakhine state, Amnesty International says hundreds of fleeing Rohingya have been detained and forcibly returned to an uncertain fate since October - a practice it says should end. Bangladesh does not recognise the Rohingya as refugees.

Read more: Bangladesh presses Myanmar on Rohingya

Anger is building in Myanmar's Muslim-majority neighbours

Leading regional newspapers have condemned Asean's inaction, with Thailand's The Nation describing it as an "accessory to murder and mayhem".

A meeting of Asean foreign ministers to discuss the crisis was held on 19 December in Myanmar's capital, Yangon, but was dismissed, external as "largely an act of political theatre" by the Asean Parliamentarians for Human Rights grouping.

Indonesia's ambassador to London, Rizal Sukma, told the BBC in December that a comprehensive approach was needed.

He said an investigation with regional participation should be launched and that his country stood ready to participate if any such commission was to be formed.

What is the UN doing?

A UN spokeswoman in 2009 described the Rohingya as "probably the most friendless people in the world".

The UN human rights office recently said for a second time this year that abuses suffered by them could amount to crimes against humanity. It also said that it regretted that the government had failed to act on a number of recommendations it had provided, including lifting restrictions of movement on the Rohingya.

It has called for an investigation into the recent allegations of rights abuses, as well as for humanitarian access to be given.

Images of Rohingya migrants stranded at sea last year briefly captured the world's attention

The UN's refugee agency says Myanmar's neighbours should keep their borders open if desperate Rohingya once again take to rickety boats to seek refuge in their countries, as happened in early 2015.

Spokeswoman Vivian Tan said now would be a good time to set up a regional task force that had been proposed to co-ordinate a response to any such movements.

Read more: Kofi Annan downplays Myanmar genocide claims

Separately, former UN-Secretary General Kofi Annan is heading another advisory commission currently looking into the general situation in Rakhine state after being asked in August by Ms Suu Kyi.

But some have questioned how useful this commission will be, given the exhaustive number of reports that already exist. Its report, in any case, will not be released until later this year.

Reporting by Kevin Ponniah.

- Published22 November 2016

- Published21 November 2016

- Published24 August 2016

- Published23 November 2016