The twilight of Tokyo's legendary fish market

- Published

Toichiro Iida: 'We built this place - our culture, our jobs made this place'

The Tsukiji fish market is probably the rudest place in Japan.

If you've got an image in your mind of cheery fishmongers bowing and wishing you the Japanese equivalent of "top of the morning", forget it.

You get pushed and shoved, told "you're in the way!" At every step you're nearly run down by a three-wheeled electric cart careening through the tiny alleyways.

The message is clear - if you don't work here you're not really welcome.

Nor is Tsukiji any sort of architectural gem. Anyone expecting a Japanese version of Istanbul's Grand Bazaar is going to be disappointed.

Tsukiji is a sprawling collection of corrugated iron sheds put up in the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake. It's old, rundown, dirty and overcrowded.

But you don't come here for architecture. You come for the fish and in this Tsukiji really is like nowhere else.

For years Tsukiji has been famed for its tuna

Every fish you've ever heard of is traded here, and many you haven't. There are giant spider crabs from Russia, scallops and sea urchin, squid and octopus, oysters and crayfish, salmon roe and sea cucumber.

But what Tsukiji is really famous for is tuna. More giant Pacific and Atlantic bluefin tuna are traded here than anywhere else in the world.

The action starts a little after 4am. In a long refrigerated hall, hundreds of shiny black and silver tuna are laid out in neat rows.

Rows of tuna are inspected by prospective buyers before the auctions start

Some are 1.5m (5ft) long and weigh over 200kg (441lbs). Men in blue overalls and wellington boots are bending over, pulling open the gills and peering inside. These are the wholesalers who have licences to bid in the morning auctions.

At 5am the auction bells start ringing. The auctioneers step on to small wooden stools and the bidding begins.

The pace is frenetic. Six auctions are going at once. One auctioneer shouts, two others chant and the nearest sounds like he is singing.

There are maybe 1,000 tuna laid out here, but it's all over in a matter of minutes. The 200kg monsters are hauled away on handcarts by their new owners.

The auctioneering can be frenetic

At his shop, deep in the bowels of the market, Toichiro Iida is waiting as one of the huge tuna is hauled in.

Now the real work begins.

First the fish is carefully washed and scrubbed. A muscular young man picks up a terrifying-looking knife called a 'Maguro-Bocho'.

The blade is 1.5m long and extremely sharp. Still, it takes all his strength and the help of a colleague to cut through the fish. After each cut, the meat is carefully wiped clean with a white cloth.

The final delicate jointing is done by Iida-san himself. His customers call in their orders - 2kg for this one, 5kg another. Some customers turn up to watch in person.

"Our customers trust me," Iida-san tells me.

"My eyes, my skill to find the fish which they like. If they come here I want to explain how it is, where it was caught, how it was caught, what it will taste like."

Carefully Iida-San takes another knife - this one the size of a samurai sword. In one smooth movement slices through the meat. Each joint is again carefully wiped with another fresh white cloth.

Finally the meat is gift-wrapped in dark green tissue paper, packed in ice, and dispatched to the customer. By lunchtime it will be served at the most expensive sushi restaurants in nearby Ginza.

The soul of Japan's Tsukiji fish market

Controversial move

Iida-san's family has been doing this for eight generations. In the 1850s, when the shoguns still ruled Japan, his forebears had a shop in the old fish market near Nihonbashi bridge.

That was destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. In 1935, his grandfather moved to the new Tsukiji market.

Now they have been told to move again, across Tokyo Bay to an artificial island that used to be home to a chemical plant. The new market is beautiful, with vast white air-conditioned halls.

But no one is happy. For Iida-San, it's too far from his customers.

"I don't want to move. Ginza has 200 sushi shops. That culture was made by this place because we are close. It's only a 10-minute walk from there to this market," he says.

The new fish market is located on an artificial island

The new site is also contaminated. The old chemical plant seriously polluted ground water beneath the new market. It was supposed to have been cleaned up.

But Tokyo's recently elected governor, Yuriko Koike, ordered new tests. Those have found benzene levels 79 times higher than government safety limits.

"I find myself with a renewed sense of surprise at how things have turned out," the chairman of the Tsukiji Market Association, Hiroyasu Ito, told the Kyodo news agency.

That's a bit of Japanese understatement. The site of the new market was supposed to have been covered with a thick layer of clean soil before construction began. Now it turns out that was never done.

Some fish wholesalers say they suspect the old Tokyo administration may have altered data in the original ground water tests in order to get the market move approved.

For the traders, it means more waiting and more uncertainty.

On the day I visit Tsukiji, it's supposed to be the last New Year auction ever to be held here. There's always excitement for the first big auction of the year, mainly because of the antics of one man.

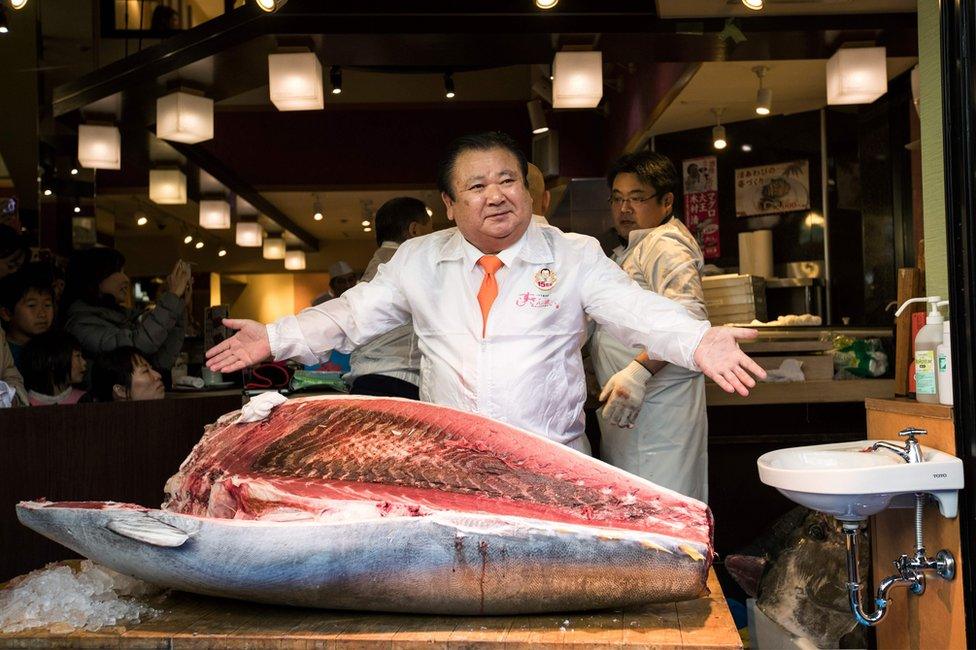

Kiyoshi Kimura is the president of Japan's most successful sushi chain. Each January the rotund figure of Mr Kimura can be seen pushing the bids to astonishing levels.

In 2013 he paid over $1.7m (£1.4m) for a single 222kg bluefin. This year the bidding is a little more modest. He manages to net a 212kg fish for just 74 million yen ($652,000, £538,000).

Mr Kimura owns the restaurant chain Sushi-Zanmai

At that price Mr Kimura is making a massive loss on every piece of sushi from the fish. Of course, it's a publicity stunt. His astronomic bids gain him headlines across Japan and around the world.

For some watching from the sidelines, Mr Kimura's annual stunt is in poor taste.

The world's appetite for bluefin tuna is running far ahead of the fish's ability to reproduce. Latest estimates suggest that since the 1960s stocks of Pacific bluefin have fallen by more than 95%.

Attempts have been made to impose a temporary ban on catching Atlantic bluefin tuna to allow the stocks to recover. In 2010 a proposal to ban international trade in Atlantic Bluefin tuna was tabled at a meeting of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), but it was rejected after a majority vote with Japan leading the opposition.

Toichiro Iida has seen the effect.

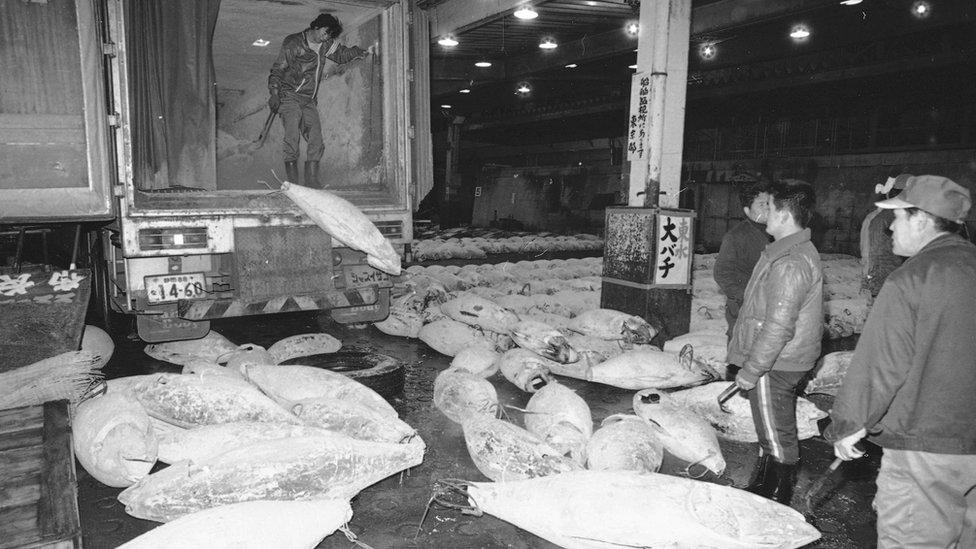

Bluefin tuna stocks have plunged in recent years

"When I started working in this market every day at the auction we had maybe 5,000 frozen tuna and 2,000 to 2,500 fresh tuna.

But now we have 1,000 or less frozen tuna each day, and fresh tuna is 200 or 100 or less. We don't have enough fish to sell to our customers."

I ask him if he now fears for the future of his business.

"Yes," he says, nodding his head vigorously. "I think maybe it's going to be like what happened to the whale."

- Published22 December 2016

- Published18 January 2017