The little boy killed at the market

- Published

Eight-year-old Zain was waiting for his brother when the bomb went off

The Hussains are one of many families in mourning after Saturday's bomb attack in the city of Parachinar in north-west Pakistan.

One of the poorest in the area, the family depends on wages earned by Jamil Hussain, a labourer in Karachi, and his 15-year-old son, Sabil Hussain, who works at a poultry shop in Parachinar.

Sabil's younger brother, Altaf, 12, takes a handcart to the city's vegetable market each morning which he hires to traders who buy vegetables at auction and need to move them to their shops.

Until last Saturday, his eight-year-old brother, Zain Haider, used to go with him to the market to scavenge leftover vegetables for the family kitchen.

On Saturday, while Zain was stuffing the vegetable waste into a shopping bag, Altaf was asked by a trader to cart his merchandise and he told Zain to wait for him there.

Minutes later the bomb went off, blowing smoke, dust and bits of shattered crates and vegetables into the air.

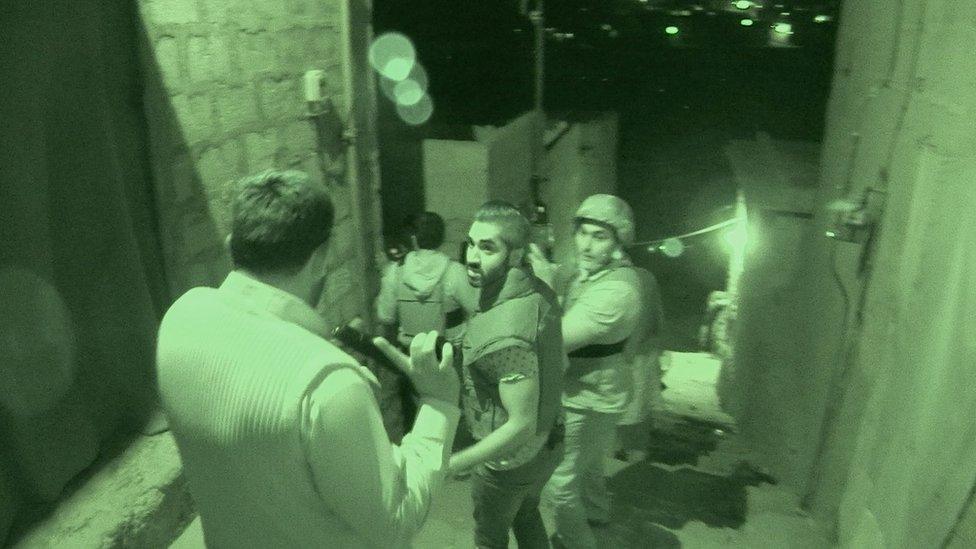

The blast at the weekend killed dozens of people

"Altaf couldn't return to find Zain immediately because there was a commotion and people were running helter-skelter all over the place," says Sabil Hussain, whose poultry shop is 10 minute's walk from the site of the blast.

"Half an hour later I went home to find Altaf in a state of shock. He was pale. He said he couldn't find Zain but was able to find his shoes, a pair of worn-out trainers, which he brought home."

Zain was proclaimed dead at a hospital where local transporters had rushed all the dead and injured.

Twenty-five people were killed on the spot.

The attack is the eighth major bombing in Parachinar since 2007. More than 500 people have died in these attacks. Many more have been killed in smaller attacks.

"By this count, Parachinar is the second most frequently targeted city by the militants after Peshawar," says Haji Faqir Hussain, the head of a council of elders of local tribes.

War with Taliban

Saturday's blast came weeks after the head of a Pakistan Army brigade stationed in the region directed local tribes to hand over heavy weapons to the government by early February.

The semi-autonomous tribal areas of Pakistan turned into large privately owned dumps of heavy weapons which proliferated because of the Afghan war in the 1980s.

Parachinar's market lay in disarray after the bombing - its eighth in 10 years

The two tribes of Kurram - the Turi and the Bangash - own scores of light and heavy machine-guns, rocket-propelled grenades and even a few anti-aircraft guns, held in community-managed stockpiles in several locations along the border of Kurram Agency, where Parachinar is the main town.

The tribes are reluctant to part with their weapons for two reasons.

First, Kurram is the only one among Pakistan's seven semi-autonomous tribal districts which is inhabited by Shia Muslims.

The district is surrounded on three sides by Afghan territory where elements linked to the Pakistani Taliban and the so-called Islamic State group have carved sanctuaries. These elements adhere to a hard-line Sunni version of Islam which is fiercely anti-Shia.

They see Shias as heretics and consider it their sacred duty to eliminate them from the face of the Earth.

The district has also faced similar threats from Pakistani territory to the east, which until 2014 served as a sanctuary for Sunni hardline militant groups.

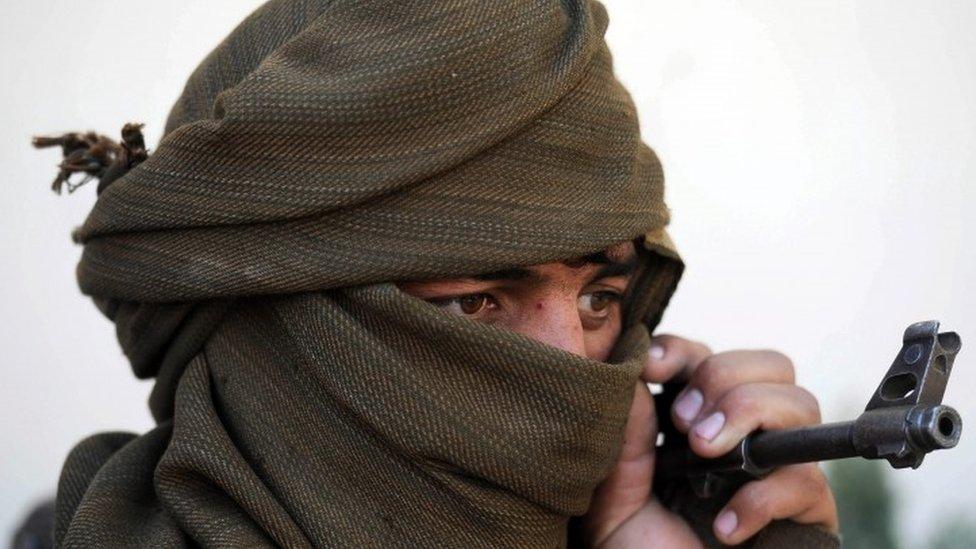

This Shia village on the Kurram river was destroyed during a conflict between the Turi and the Taliban

During 2007-8, the Turi and Bangash tribes of Kurram fought a protracted war against the Pakistani Taliban to prevent them from over-running Kurram and capturing strategic routes to attack the Afghan capital, Kabul, just over 90km (55 miles) north-west of the western tip of Kurram.

They have also conducted short expeditions against Sunni tribes in the west to secure their border against attempts by Sunni militants to infiltrate from there.

Second, there are lingering doubts about both the intentions and the ability of the military to defend them.

"Even though the military claims that they can defend us, we can't forget that we were left to our own devices when the Taliban captured our areas and tried to force their way to Parachinar," one local elder said.

"And [the military] still continue to back some Taliban groups, who lurk on our border and may at any time in future want to force their way to our western border for their war on Kabul."

'We won't surrender arms'

Haji Faqir Hussain says that giving up their weapons would amount to "stripping ourselves of our only means of survival".

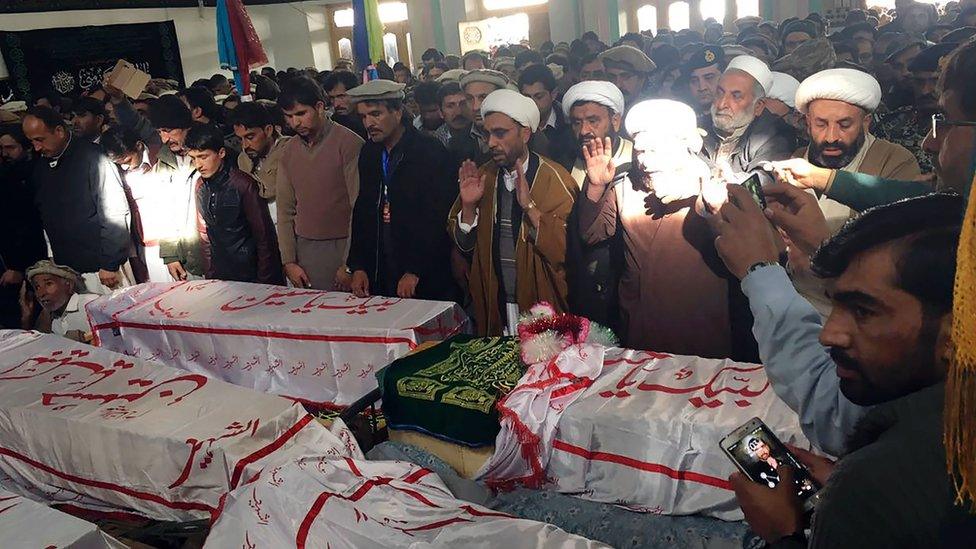

Victims of the Parachinar blast were laid to rest shortly after the attack

"We are surrounded by the Taliban and Daesh [IS] like the tongue [is surrounded] by teeth. We have never acted against the interests of the government, and we can't fight it, but we want them to know that parting with our weapons would mean that we are surrendering our women and children to the enemy with the permission to do with them what they want."

People in Kurram refer to Saturday's bombing as proof that they are still not safe against anti-Shia militants. There is also a fear that the government may blame the bombing on Shias and thereby force them to surrender their arms.

"On Sunday they arrested seven people in connection with the bombing, but most of them are local Turi tribesmen engaged in small-time vegetable businesses," says Sajid Hussain Turi, a member of the national parliament from Kurram.

"We condemn these arrests. They should be looking for Taliban who claimed responsibility for the attack."

'Dad doesn't know'

While the Shia tribes of Kurram are lobbying to keep their weapons, the family of little Zain Haider is trying to come to terms with its own problems.

"My father has a tough life in Karachi, and it's long distance travel involving lots of money (Karachi is 1,400km south of Parachinar). So we haven't told him [about Zain's death]," says Sabil Hussain.

For the moment, he is struggling to take care of his mother, whose blood sugar levels have been unstable since Zain's death.

And the fact that her husband doesn't know is also playing on her mind.

When will they tell him?

"As time goes by, it will become harder, but we'll have to take it how it comes," says Sabil.

- Published21 October 2010

- Published21 January 2017

- Published3 March 2016

- Published12 August 2022

- Published14 December 2015