Viewpoint: Will Pakistan ever stamp out extremism?

- Published

The army school attack in 2014 led to a comprehensive counter-terror plan, but impetus was lost

As Pakistan detains an alleged mastermind of the Mumbai attacks, Ahmed Rashid argues that Pakistan needs a broader, better co-ordinated strategy from state institutions and a willingness to face up to unpleasant truths if it really wants to curb resurgent extremism.

Pakistan faces a renewed threat of rising Islamic extremism, vigilantism, attacks on minorities and a reluctance to face up to how these threats are internally rather than externally inspired.

Also missing is the lack of a comprehensive narrative against extremism, articulated unanimously by all bodies of the state and civil society.

The result of the failure to push forward a clear counter-terrorism and counter-extremism narrative that embraces the entire public domain is that some extremist groups continue to be tolerated by elements of the state.

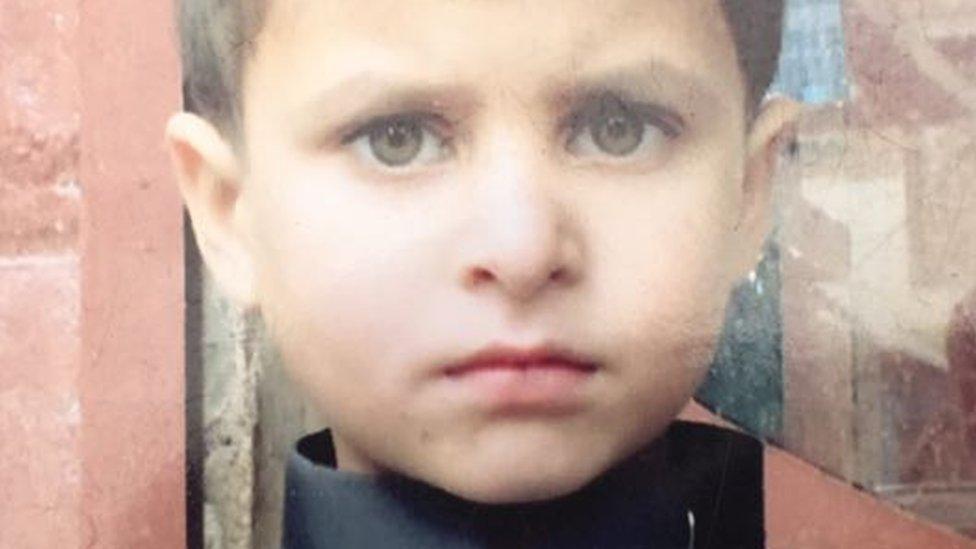

Just over two years ago, on 16 December 2014, an attack on an army-run school in Peshawar which killed 150 people - the majority of them children - galvanised the civilian government, opposition parties and the military to articulate the need for a comprehensive counter-terrorism plan.

For the first time there emerged a 20-point National Action Plan , external- a list of pointers of what needed to be done, endorsed by the military and all political parties.

However the 20 points were never turned into a comprehensive winning strategy or a common narrative and the fight against extremism has diminished ever since.

The army's Operation Zarb-e-Azb, launched six months earlier, had cleared out North Waziristan, a key staging area for dozens of militant groups - many of them foreigners.

Other military operations also took place, dramatically reducing terrorist bombings nationwide. But they were always going to be tactical operations, which still needed to be backed by a strategic plan carried through by the government.

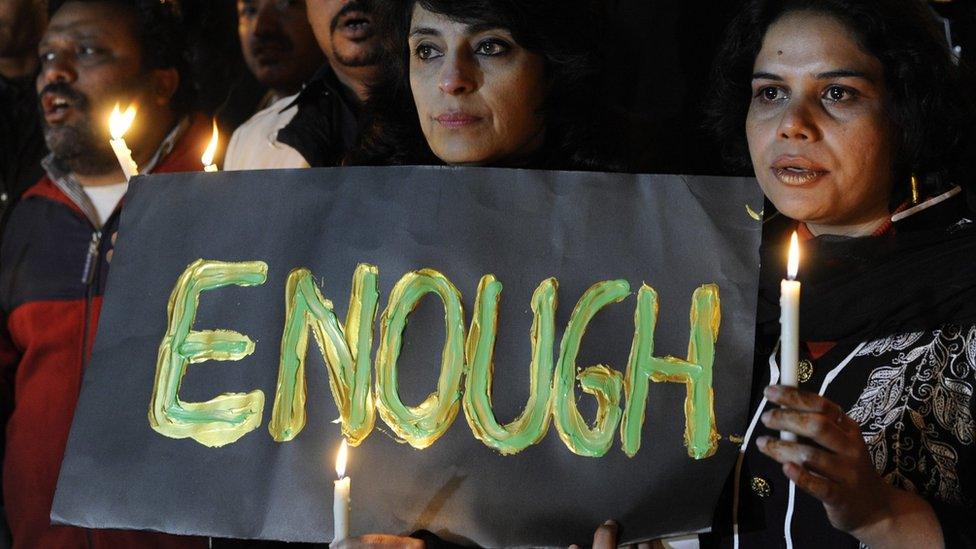

Pakistanis want the government to tackle the extremist threat

A faction of the Pakistani Taliban said they were behind a recent bomb attack in a mainly Shia area in Parachinar, Peshawar

It was the task of the civilian government to carry out educational reforms, job creation, co-ordination among intelligence agencies, galvanising the legal system, a ban on hate speech and a clear strategy of de-radicalisation of the nation's youth.

All these aspects of a strategy to be carried out by the government, as opposed to tactical military operations, have been missing, as the government has slipped into inertia and paralysis.

At the same time the state gave a pass to those extremist groups who were supportive of Islamabad's foreign policy towards India and Afghanistan.

The lack of a strategy and the state support offered to some groups has led to a growing mood of defiance among extremist organisations.

In the past few weeks five bloggers have disappeared (three, including liberal activist Salman Haider, have now returned home), some threatened journalists and civil society activists have fled abroad, non-governmental organisations have been accused of being unpatriotic, the Ahmedi community has been ferociously attacked and minority Shia Muslims have been massacred.

Hate speech has become a growing phenomenon in some media outlets, especially television, while increasingly journalists and others are threatened with being charged with blasphemy, against which there is little legal defence. Innocent lives are at risk as public incitement and witch hunts continue.

Earlier this week, Hafiz Saeed, the cleric blamed by the US and India for masterminding the Mumbai attacks, was placed under house arrest. The move is being seen as a response to suggestions by US officials that the Trump administration may ban his Jamaat-ud-Dawa charity, seen by the US as a front for terrorists. However a military official said it was "a policy decision" and had nothing to do with any foreign pressure.

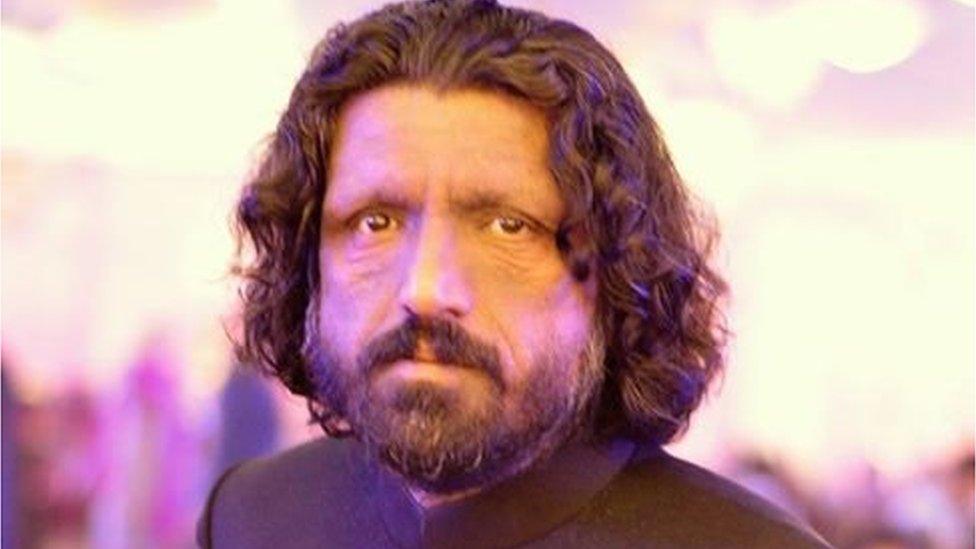

Pakistani blogger Salman Haider went missing for more than 20 days - he has not yet disclosed where he was

Pakistan's media regulator has just banned Aamir Liaquat Hussain, a high-profile TV host, accusing him of hate speech that could put lives at risk.

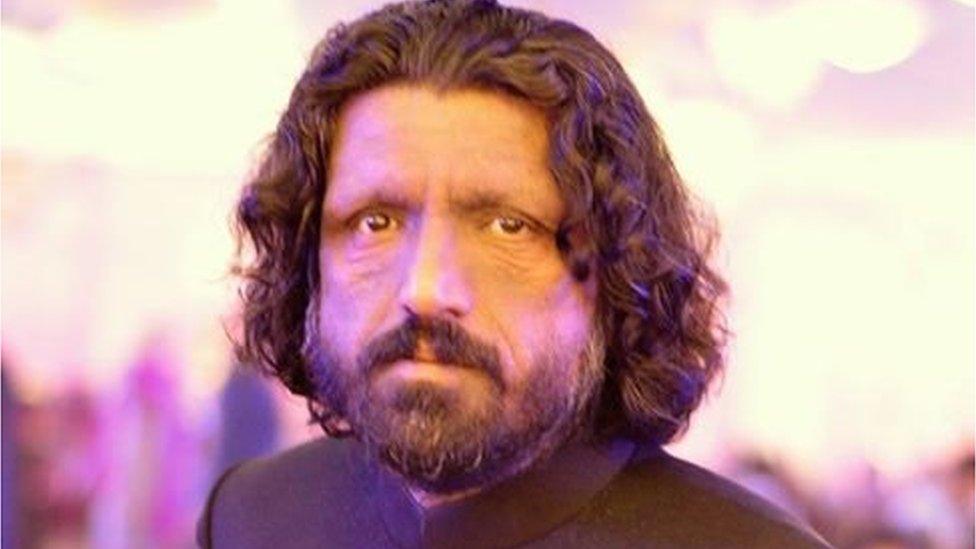

Hafiz Saeed is accused by the US and India of masterminding terror attacks

A key aspect of the growing defiance of extremists is the insistence that Pakistan's neighbours are to blame for acts of terrorism rather than recognising that it is a home-grown problem.

When former army chief Gen Raheel Sharif took over the army three years ago, he repeatedly said that the country must look into itself to counter extremism and not blame foreign powers.

That was music to the ears of most Pakistanis, who hoped that the state would tackle the very real threats at home rather than blame outsiders.

Yet over the past year the state has been insisting that all major acts of terrorism have been perpetrated by India or Afghanistan, rather than domestic terrorists.

Meanwhile, the civilian government has been indecisive and hesitant as to who to blame, while in its home base of Punjab it has clearly been allowing extremist groups to flourish.

The conflict between civil and military agencies has left the public bewildered, giving further space for extremist ideas to flourish. This confusion has clouded out the need for a common and united narrative as to how to deal with extremism.

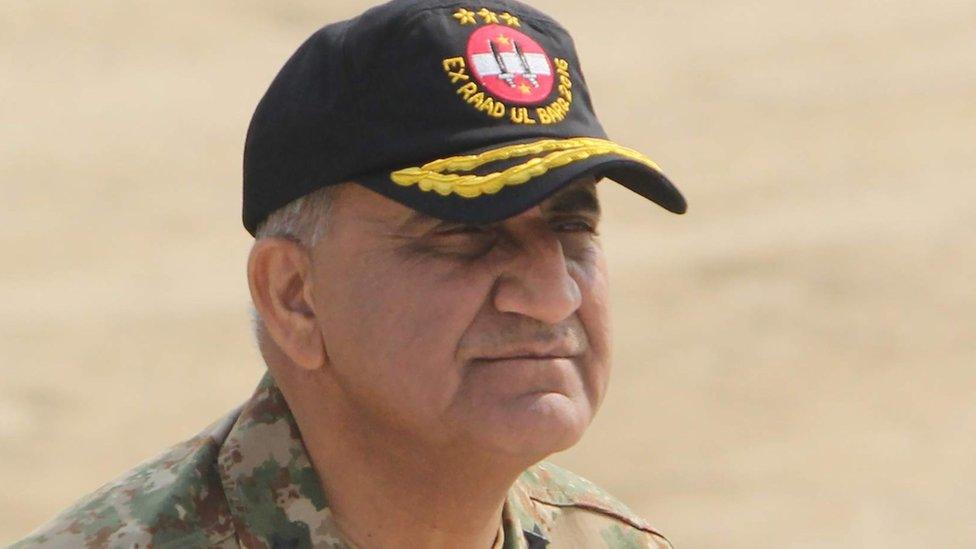

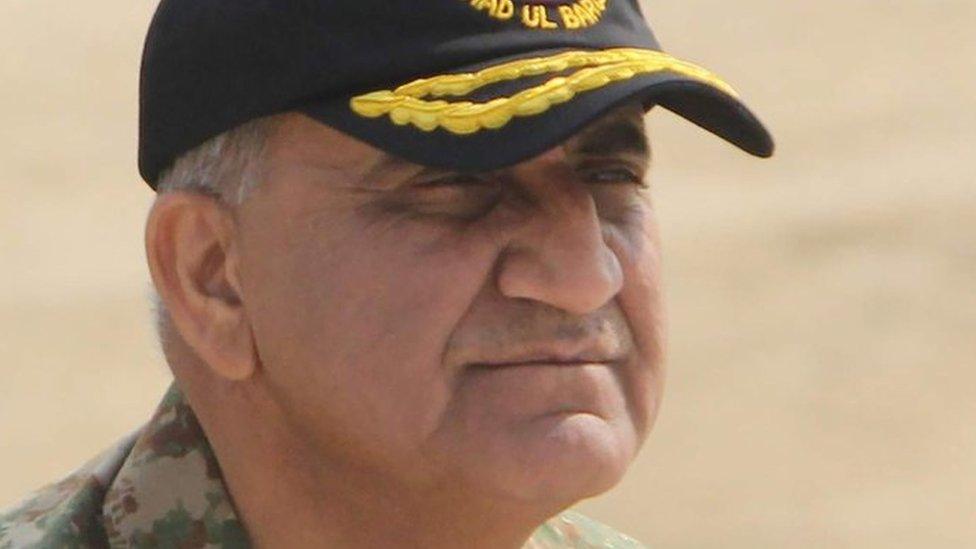

Canadian-trained Gen Bajwa has not set out where he perceives the terror threat exists

So far, the new army chief Gen Qamar Bajwa has not categorically restated that terrorism is a domestic rather than a foreign creation.

Meanwhile, relations with India and Afghanistan have worsened and other neighbours have distanced themselves from Pakistan, leading to what many experts have claimed is the country's growing isolation in the region.

If Pakistan is to defeat extremism, a comprehensive strategy and common narrative, jointly agreed upon by the military and the politicians, needs to be implemented. Both need to ensure that all parts of the state are fully carrying out their responsibilities.

Most importantly, the narrative that government agencies build up must be consistent and carry forward badly-needed social reforms that will promote de-radicalisation of young people.

Pakistan needs a single, inspired, pragmatic and inclusive narrative that is strictly adhered to and can raise the public's morale instead of adding to their confusion.

Ahmed Rashid

Ahmed Rashid is a Pakistani journalist and author based in Lahore

His latest book is Pakistan on the Brink - The Future of America, Pakistan and Afghanistan

Earlier works include Descent into Chaos and Taliban, first published in 2000, which became a bestseller

- Published28 January 2017

- Published26 January 2017

- Published27 November 2016

- Published13 December 2015