North Korea: What can the outside world do?

- Published

North Korea has ramped up its missile testing in recent months

"Rogue nation". The "greatest immediate threat". North Korea has been called many things, few of them complimentary.

The government has been accused of brutally oppressing citizens while ruthlessly pursuing the development of nuclear weapons.

In the past year it held its fifth nuclear test, launched several missiles and - most believe - assassinated its leader's half-brother using a chemical weapon.

Most recently, it has conducted its first test of what it claims is an inter-continental ballistic missile, a move that - if verified - increases the threat it can pose to its enemies and ratchets up international tensions.

But why is North Korea such a problem - and why can no solution be found?

A potted history

The US and the Soviets divided Korea into two at the end of World War Two. Reunification talks failed and by 1948 there were two separate governments. The 1950-53 Korean War entrenched the split.

North Korea's first leader was Kim Il-sung, a communist who presided over a one-party state, and the grandfather of current leader Kim Jong-un.

It remains one of the world's poorest nations. Its economy is centrally controlled, its citizens have no access to external media and, apart from a privileged few, no freedom to leave.

Most worryingly, it has conducted five nuclear and multiple missile tests that demonstrate progress towards its ultimate goal of building a nuclear missile.

Is Kim Jong-un (centre) waiting until he can negotiate from a position of greater strength?

So what about negotiations?

There have been several rounds. The most recent, involving China, South Korea, Japan, Russia and the US, initially looked promising.

Pyongyang agreed to give up its nuclear work in return for aid and political concessions. It went as far as blowing up the cooling tower, external at its plutonium production facility at Yongbyon. But then things faltered. The US said North Korea was failing to disclose the full extent of its nuclear work. Pyongyang denied this, but then conducted a nuclear test. So, since 2009, there have been no meaningful discussions.

John Nilsson-Wright, senior fellow for north-east Asia at think-tank Chatham House, says that North Korea, judging from its recent provocations, is not interested in negotiating at the moment.

"This is because Kim is determined to push forward on military modernisation, so rationally it is in his interests to delay."

But economic pressure would work, right?

The UN and several nations already have sanctions in place against North Korea, targeting its weapons programme and financial ability to function abroad.

Meanwhile food aid to North Korea - which relies on donations to feed its people - has fallen in recent years as tensions have risen.

But these measures do not seem to be slowing down North Korea's ability to move forward on the military front.

China is widely seen as the nation most able to impose economic pain on North Korea. Experts say targeting the intermediaries that keep North Korea moving - like Chinese banks - would make a real impact, as would targeting the oil that Pyongyang imports from China.

This is some movement on this. A Reuters report in late June, external, citing unidentified sources, said China's state oil giant had suspended sales to Pyongyang, though it suggested the decision was commercial. The US, meanwhile, has imposed sanctions on a Chinese bank accused of laundering North Korean money.

But the key problem is that China does not want to take actions that would destabilise the government in North Korea and potentially unleash chaos on its border.

So, John Nilsson-Wright says, China has been trying to play the role of honest broker, lobbying the US to talk to Pyongyang. But the US, Japan and South Korea have made it very clear that the North must show a real willingness to compromise before talks become an option.

North Korean coal exports have been targeted - but the government shows no signs of collapse

Is there a military option?

Not a good one. It is generally thought that military action against North Korea would lead to very high military and civilian casualties.

Finding and eliminating North Korea's nuclear stockpile would be hard - experts suspect assets are buried deep underground. Moreover the North is heavily armed, with an arsenal of missiles putting Seoul (and beyond) in range, chemical and biological weapons, and about one million troops.

"The risk is that it provokes a counterattack that is massively costly to South Korea," says Dr Nilsson-Wright.

What about assassination?

In the past South Korea has talked overtly about a "decapitation" strategy - a targeted attack to remove Kim Jong-un and his leadership.

This could be a tactic to deter North Korea from further provocations or to force it back to the negotiating table, says Dr Nilsson-Wright. The strong view in Seoul, he says, is that the only way to get the North back to the negotiating table is to make the government feel so insecure that it feels it has no choice.

There are also big questions around who might fill the vacuum if a "decapitation" went ahead. The elite have a vested interest in the survival of the Kim government and there is no political opposition.

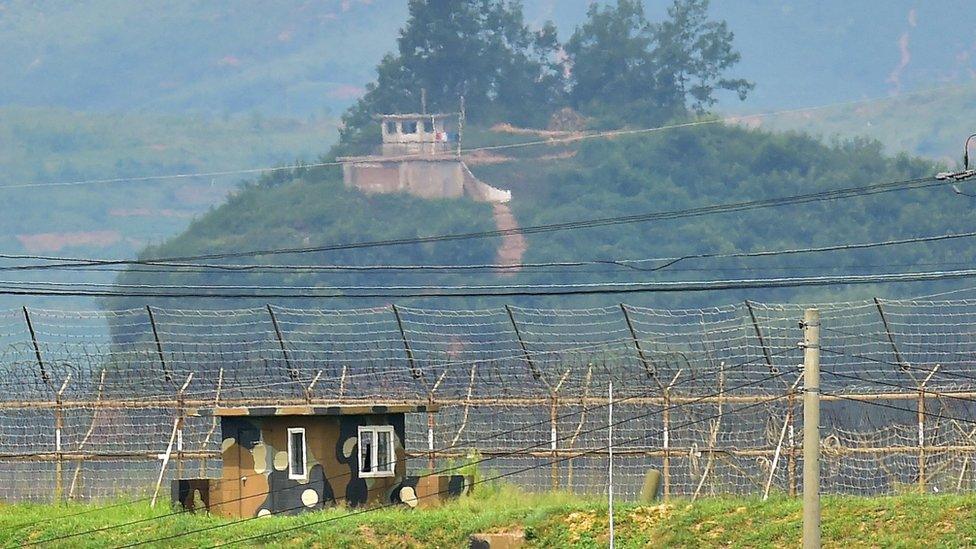

Both Koreas have firepower and troops ready for any conflict

How about a gradual opening?

For a while some thought that the way to bring North Korea into the international community was to help it open up gradually, through small economic reforms, using the model of China's transformation after the death of Mao Zedong

There were signs Kim Jong-il - the leader's late father - may have been interested in this approach, as he made several trips to Chinese industrial zones. The key supporter of this, however, was thought to be Chang Song-thaek, the leader's uncle. But Kim Jong-un had him executed in December 2013, calling him a traitor who planned to overthrow the state.

Kim Jong-un has not yet visited China - in fact, he has not visited any foreign country since becoming leader in 2011. And while he has talked of economic growth, the military programme appears to be his priority.

Could a credible opposition emerge?

This is very unlikely. One-party rule is absolute in North Korea. Citizens are encouraged to worship the Kim dynasty, which is portrayed as the only institution keeping them safe from external aggression.

There are no independent media. All TV, radio and newspapers are state-controlled and North Korea has created its own internet so citizens have no electronic access to the outside world.

There is a limited flow of information across the Chinese border, including DVDs which are smuggled in. But in general North Korea exercises very tight control over its citizens. The government has informants everywhere looking for signs of dissent and penalties are severe. Offenders (and sometimes their whole families) can be sent to labour camps where many die.

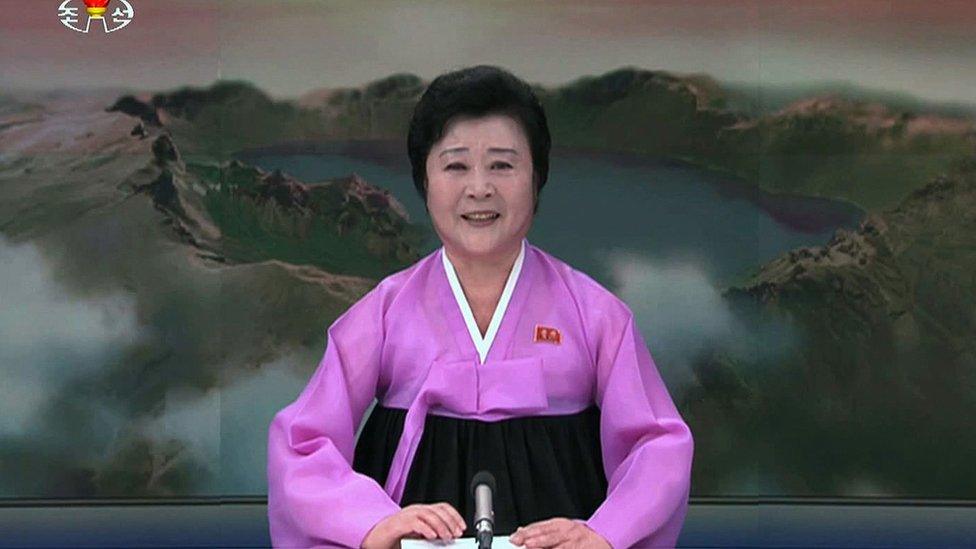

The state controls what North Koreans can and cannot watch, hear and read

So what's the best option?

There needs to be a mixture of pressure and dialogue, says Dr Nilsson-Wright. Pressure, he suggests, could involve some combination of enhanced sanctions, the relisting of North Korea as a State Sponsor of Terrorism (it was removed from the list in 2008), and close work with China to inflict real pain. Possible incentives could include formal diplomatic recognition by the US or a peace treaty (the two Koreas remain technically at war).

Key to this approach would be co-ordination between the US, China, South Korea and Japan. But there are problems. After initial apparent warmth, ties between the Trump administration and Beijing seem to be cooling. In June US President Donald Trump tweeted that China's approach to North Korea had "not worked out".

Ties between Japan, South Korea and China remain fractious over historical issues. Beijing is also fiercely opposed to the deployment by the US of a Thaad missile defence system in South Korea. In Seoul, new liberal President Moon Jae-in must walk a fine line balancing the interests of his electorate, biggest military ally and powerful neighbour. So there are divisions to exploit.

"That is why North Korea is pushing it now - it knows it has a window on which to capitalise," Dr Nilsson-Wright argues.

- Published25 February 2017

- Published10 August 2017

- Published10 August 2017

- Published6 March 2017