Top US diplomat Tillerson faces first major challenge

- Published

Nuclear threats, contested territory, and a looming trade dispute await the new secretary of state in Asia

The new US secretary of state is heading off on his first trip to Asia, where diplomatic tensions run high.

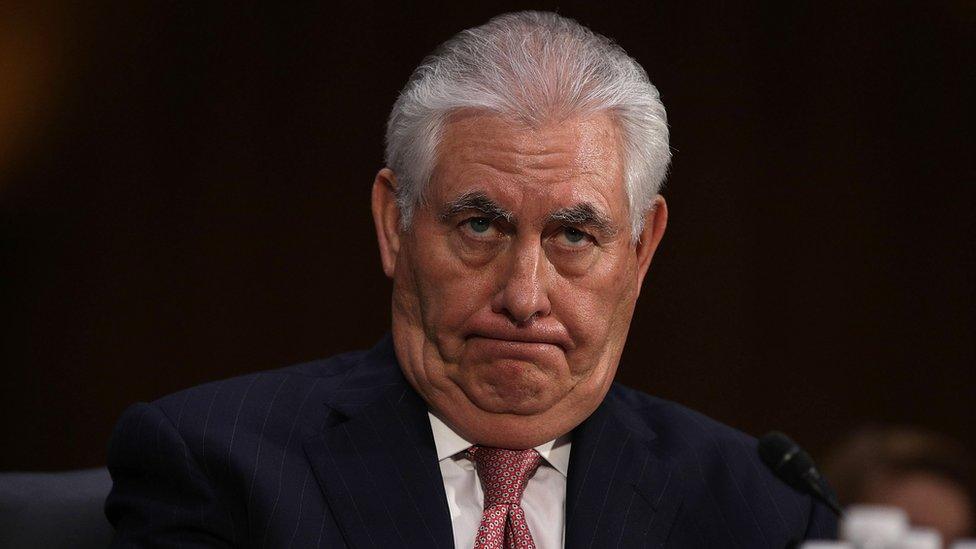

Rex Tillerson, who has no previous political experience, will be visiting countries in the shadow of North Korea's nuclear programme.

Global superpower China may be the key to that problem, and to stability in the region, but relations with the US are strained at the moment, partly over comments Mr Tillerson himself has made.

His first true test as a diplomat is a potential powder keg. So is the former oil boss up to the task?

Top diplomat, low profile

Tillerson's folksy introduction to his department: 'Hi, I'm the new guy'.

Rex Tillerson has kept a remarkably low profile in his first month or so in office, giving no press briefings in six weeks, and sticking to prepared statements.

Any hopes that reporters might see him in action on this Asia trip were dashed, however, when it emerged he wouldn't be bringing the state department press corps along.

Instead, Mr Tillerson will be taking a single reporter from a conservative website, the Independent Journal Review - because of the small plane being used, the state department said. The journalist, Erin McPike, recently wrote about Tillerson in a piece on "Exxon Mobil's special treatment from the White House, external".

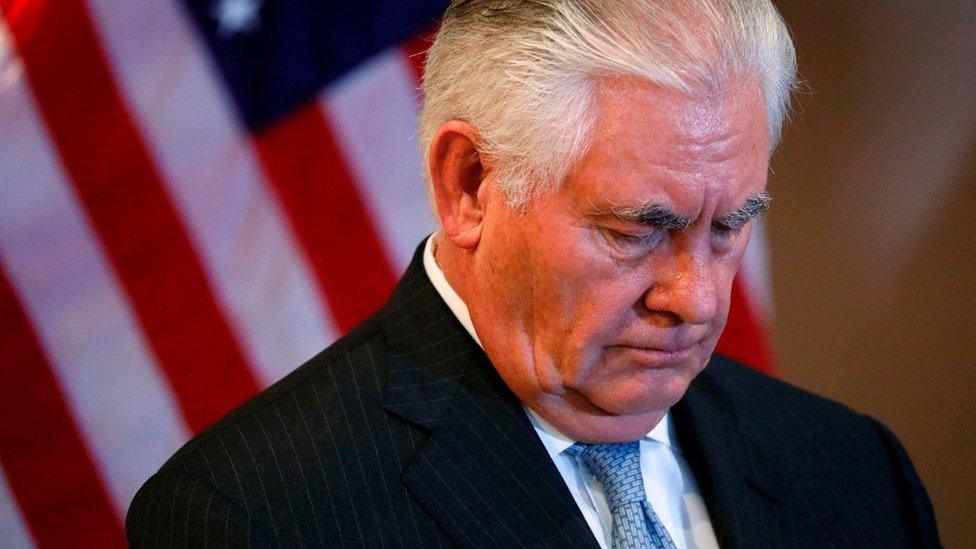

The trip is seen as important because Mr Tillerson will be trying to conduct high-level diplomacy in a region shaken by his president's public comments.

Donald Trump has tweeted that China needs to be "taken on, external" and decried the country's "military complex, external" in the South China Sea. The president has said that South Korea "makes a fortune on us, external" while the US defends it, and has accused Japan of "currency manipulation, external".

Such remarks have led to uncertainty in the region about the direction of US foreign policy, something Mr Tillerson will have to deal with.

The North Korea problem

Mr Tillerson's trip starts with Japan, which is likely to be the easiest leg of the journey. He is scheduled to meet the foreign minister, as well as Prime Minister Shinzo Abe - who Trump has already met, and "had a great time, external" with.

But the military threat from North Korea is likely to dominate the discussion.

How do you solve a problem like North Korea?

The secretive isolationist nation has continued its development of nuclear weapons despite sanctions and threats from the international community. Two nuclear explosion tests and more than 20 missile launches in the past year have increased tensions.

Both Japan and South Korea, which are US military allies and host US troops, are within missile distance of North Korea.

But it is China, as North Korea's only ally on earth, which holds the power to affect change.

Donald Trump has accused China of ignoring the North Korea situation, and essentially allowing it to worsen.

But Beijing has taken relatively strong steps in recent weeks. Early in March, it asked Pyongyang to stop its missile tests to "defuse a looming crisis", and earlier dealt its ally a severe economic blow by banning coal imports.

Mr Tillerson is likely to urge China to do even more. But at the same time, he'll have to smooth over another row that the US is involved in.

The United States has deployed the Thaad missile defence system (that's Terminal High Altitude Area Defence) in South Korea to defend it from nuclear attack.

Unfortunately, the missile defence system's radar is extremely long range, extending into China.

"It's incredible the speed with which China's leaders can just switch on anti-South Korea sentiment here," the BBC's China Correspondent, Stephen McDonnell, said in a blog post this week.

The South China Sea problem

China's development of artificial islands with defensive capabilities in the South China Sea is deeply controversial.

"We're going to have to send China a clear signal that first, the island-building stops and second, your access to those islands also is not going to be allowed," Mr Tillerson told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in January, likening it to Russia's annexation of Crimea from Ukraine.

China says its building is legitimate and its military facilities are for self-defence

"They are taking territory or control or declaring control of territories that are not rightfully China's," he said, in remarks that might be welcomed by Japan and others who contest China's territorial claims.

But it makes the delicate negotiation with China that much harder.

For China's part, state-controlled media warned Mr Tillerson that such actions could cause "devastating confrontation" or even "a large-scale war".

A rather more emollient foreign minister told his annual news conference in Beijing that Mr Tillerson "is a person who is willing to listen and is a deep communicator."

Trade and tactics

Even if Mr Tillerson can bring calm to the South China Sea dispute and persuade Beijing to step up sanctions against Pyongyang, there's still one more problem - an economic one.

One of President Trump's first actions was to pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which would have opened up trade with Japan and 11 other nations by reducing tariffs. That's good news for China, which saw the TPP as an effort to contain its economic might, but means Japan needs to start over.

And China has its own problems with US trade policy.

Donald Trump is likely to tear up the old rulebook of how trade deals are done, says Anthony Scaramucci

During the election campaign, Mr Trump floated the idea of a 45% tariff on goods from China, and in January, a senior academic adviser warned the current trade deal was "more favourable to China than us".

Anthony Scaramucci told the BBC a trade war is "going to cost them way more than it is ever going to cost us, and I think they know that."

And while the relationship with South Korea may have long been stable, the country is in the depths of a major political crisis following the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye.

She had been a long-time supporter of US foreign policy in the region, particularly when it came to isolating North Korea.

But the current frontrunner to replace her, Moon Jae-in, has suggested a new approach might be required in handling North Korea - and has voiced concern about the US deployment of the Thaad defence system in the South.

With so many competing interests in economic and territorial disputes, and a looming military threat, Mr Tillerson will have to thread the diplomatic needle carefully - weighing each nation's goals against the desire of the US, and everyone else involved, for regional stability.

- Published12 January 2017

- Published13 January 2017

- Published14 March 2017

- Published13 March 2018

- Published10 March 2017

- Published25 February 2017

- Published2 February 2017

- Published23 February 2017

- Published27 January 2017

- Published2 February 2017

- Published8 May 2017