Liu Xiaobo: Chinese dissident and Nobel Peace Prize winner

- Published

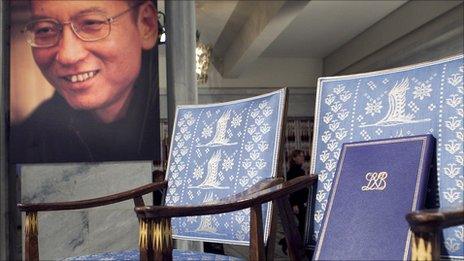

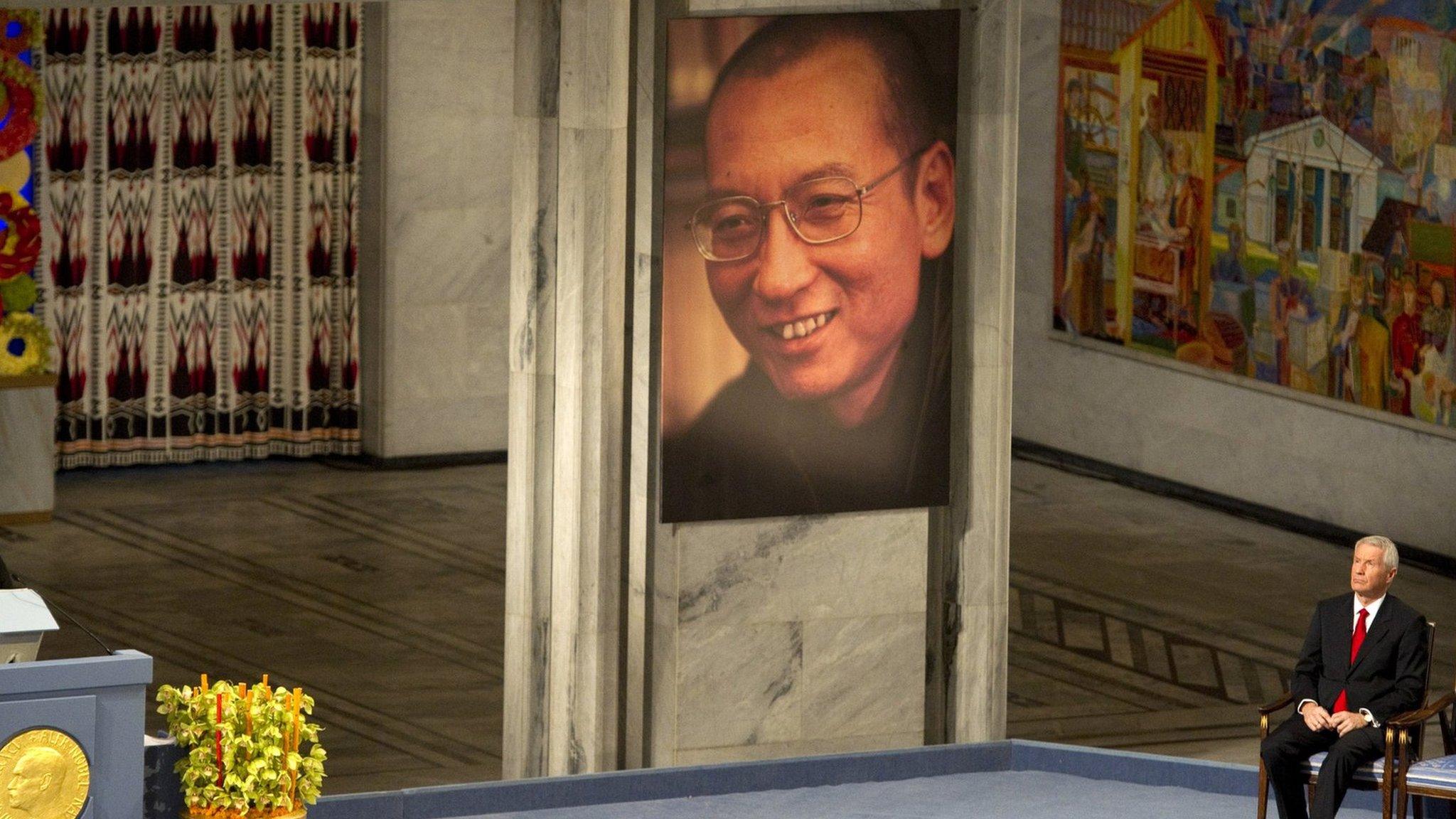

When Liu Xiaobo was formally awarded his Nobel Peace prize in 2010, he was represented at the ceremony by an empty chair.

By then, the dissident academic was in prison again, this time serving an 11-year sentence for "inciting subversion of state power" for his role in drafting a democracy manifesto for China.

But his voice was heard at the ceremony, when an actor read aloud the statement, external he had written for the court that jailed him.

He looked forward, he wrote, to the day "where all political views will spread out under the sun for people to choose from, where every citizen can state political views without fear".

'Beloved lectern'

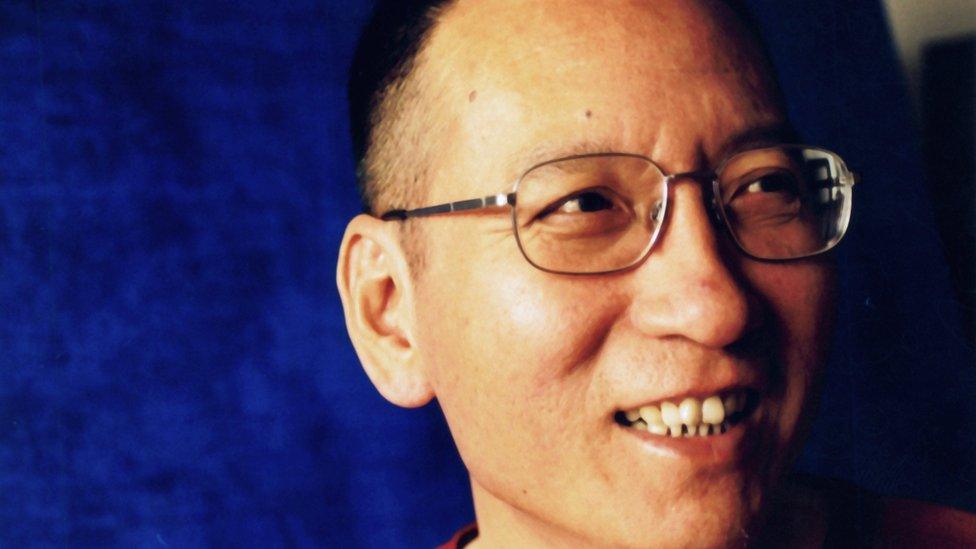

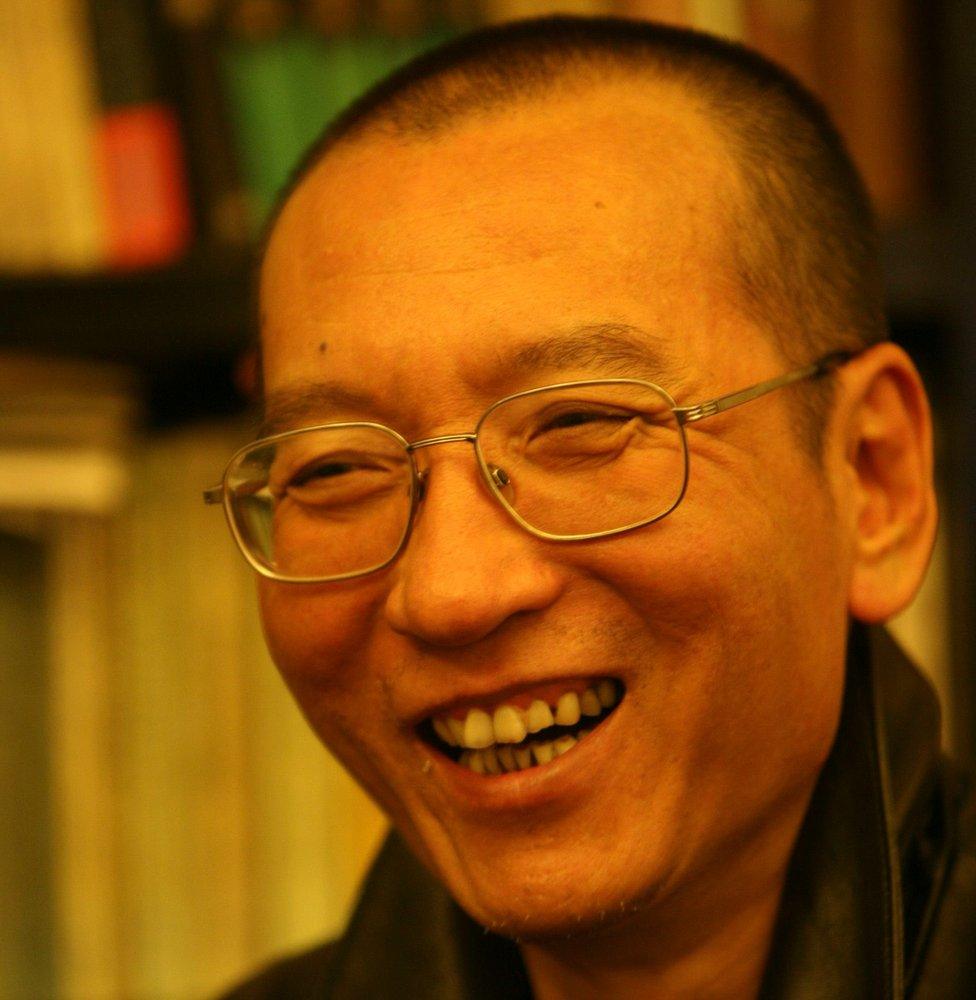

Liu Xiaobo, who was born on 28 December 1955 in Changchun, Jilin, was seen as a hero by many but a villain by his own government.

The Nobel committee described him as the "foremost symbol" of the struggle for human rights in China.

But to Chinese state media, he was a "prisoner who confronted authorities and was rejected by mainstream Chinese society".

He began life as an academic, studying literature and philosophy, and received his PhD from Beijing Normal University.

Liu Xiaobo was the "foremost symbol" of China's human rights struggle, the Nobel committee said

When the Tiananmen pro-democracy movement began in 1989, he was a visiting scholar at Columbia University in the US.

He flew back in April of that year to take part in the protests that grew into the biggest challenge to China's one-party communist government since it came to power in 1949.

But the protests came to a bloody end on 4 June as authorities ordered in troops to quash the demonstrations.

Mr Liu and others were credited with saving the lives of a few hundred protesters when the activists successfully negotiated with troops to allow a peaceful exit.

Though he was offered asylum in Australia, he turned it down, choosing instead to stay in China. He was subsequently arrested and jailed for "counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement".

As a consequence, he wrote, he lost his "beloved lectern" and could no longer publish essays or give talks in China.

After his release from prison in 1991, Mr Liu campaigned for those imprisoned for their roles in the Tiananmen movement, which saw him re-arrested and sentenced to three years in a labour camp.

'Disastrous process'

In 1996, while still in prison, he married Liu Xia, a poet and artist for whom he later described his love as "boundless".

Once his term was served, he continued with his activism even as authorities blocked him from working as a university lecturer and banned his books in China.

Chinese state censorship meant he was far better known in the West than in his home country.

Speaking to BBC Chinese in 2005, he described reforming China as a "long and tortuous process" founded in the efforts of the people.

"One can see that there are many failures and sadness during this process, and most struggle for human rights will result in failure; but it is a continuous awakening, which will not be contained by lies and repression," he said.

Then came the move that led to his longest - and final - prison sentence. In 2008, he and a group of intellectuals helped to draft a manifesto called Charter 08.

Supporters in Hong Kong protested against Mr Liu's continued incarceration in 2016

The document called for a series of reforms in China, including a new constitution and legislative democracy, and respect for human rights.

"A 'modernisation' bereft of these universal values and this basic political framework is a disastrous process that deprives humans of their rights, corrodes human nature and destroys human dignity," it said.

The charter appeared to be the last straw for the government. Two days before the manifesto was due to be published online, police raided Liu Xiaobo's home and took him away.

He was held in detention for a year before he was tried in court. Then, on Christmas Day in 2009, he was jailed for 11 years.

'Nothing criminal'

A year later, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The committee praised Liu Xiaobo, external for his "long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China".

China reacted angrily. Mr Liu was not allowed to attend the ceremony, and the world's media instead took pictures of his empty chair.

Liu Xia told Reuters that her husband wanted to dedicate his prize to all those who died in the Tiananmen crackdown. "He felt sad, quite upset. He cried. He felt it was hard to deal with," she said.

She was subsequently placed under house arrest, isolated from family and supporters. Her movements have remained restricted ever since, with no explanation from the Chinese authorities.

In June 2017, with three years left of his sentence, Chinese authorities said Mr Liu had been diagnosed with terminal liver cancer.

He died weeks later, at the age of 61. Pleas for him to leave China for medical care were rejected by Beijing, on the grounds that he was too ill to travel.

In his statement in 2009, Liu Xiaobo said he had "no enemies". He said he had felt respect from prosecutors who went on to imprison and silence him. Prison conditions, he said, had improved since his previous incarceration and management had become more humane. He noted in particular the kindness of one prison officer.

These changes, he said, made him hopeful about his country's future; that China would in the end become a free nation "ruled by law, where human rights reign supreme".

He said he did not regret having spoken out. "There is nothing criminal in anything I have done. If charges are brought against me because of this, I have no complaints."

- Published9 December 2010

- Published9 December 2010

- Published7 October 2011

- Published14 January 2014

- Published12 October 2012

- Published3 December 2013

- Published10 December 2010