Mongolian teenage girl grapples for a future in sumo

- Published

Mongolian wrestlers have dominated the Japanese sumo scene for years and Bum-Erdene Tuvshinjargal is keen to follow in their footsteps. As a girl, that means challenging centuries of tradition, but that's another fight she's ready to take on. She spoke to journalist Erin Craig at her home in Ulan Bator.

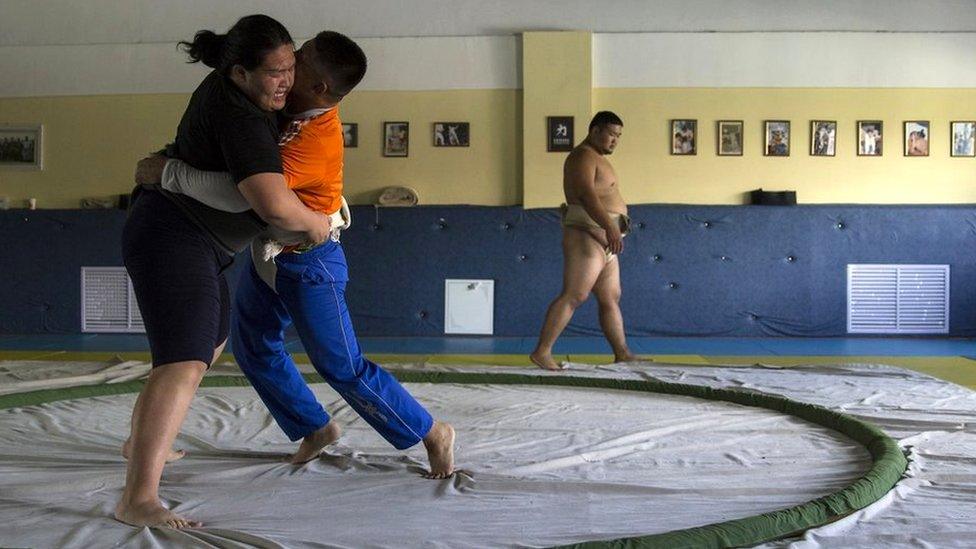

On one side of the ring squats a formidable, heavyset wrestler, the traditional mawashi wound around his waist. On the other is Bum-Erdene Tuvshinjargal, her loincloth wrapped over black spandex.

The competitors wait, stare, then cannon toward each other. They hit in the centre, straining in a slow dance of raw power.

Then Tuvshinjargal explodes forward, muscling her opponent out of the ring.

She gives a rare, brief smile as she walks off the mat.

"You can't be scared," says the 17 year old sumo world champion. "If you're scared you won't win."

As a child, Tuvshinjargal watched sumo on TV with her grandparents, never dreaming she would be a wrestler herself. She later took up judo, and in 2015 her instructor suggested trying sumo at a competition the following month.

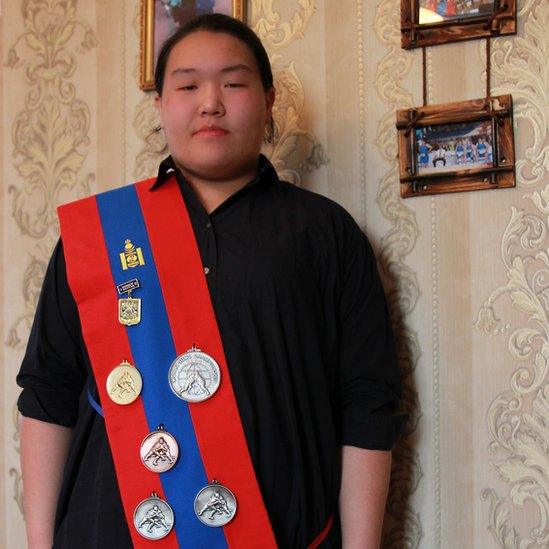

That competition turned out to be the Junior Sumo World Championships. Tuvshinjargal came home with a bronze medal. Last year she went back for the gold.

Her coach, Gankhyag Naranbat, thinks this is just the beginning. As a former rikishi - a professional sumo wrestler - and World Games gold medallist, he knows what to look for in a competitor.

"I think she will be more than three times world champion, heavyweight category," he predicts. That would break a world record - one established only last year by Tuvshinjargal's teammate, Khishigdorj Sunjidmaa.

Pushing the rice paper ceiling

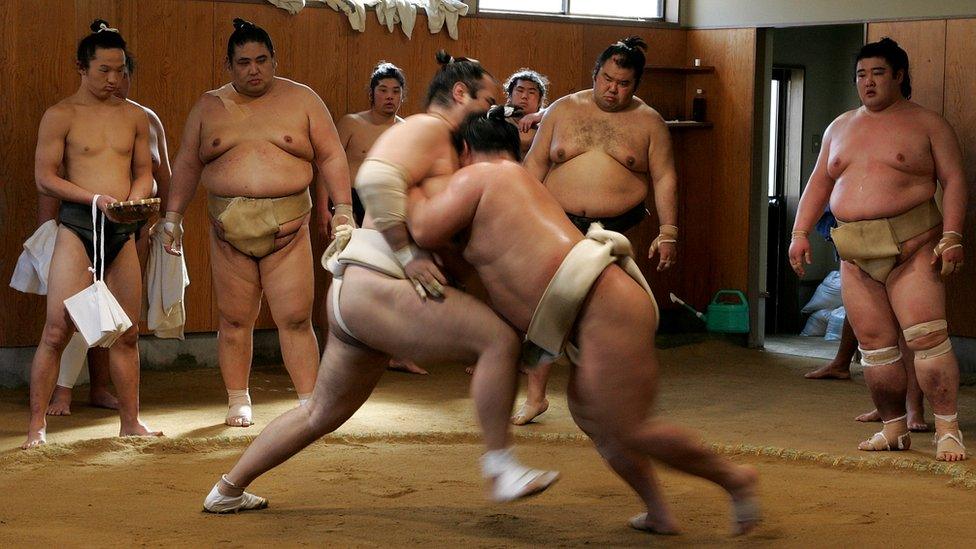

But no matter how many records she breaks, Tuvshinjargal's career is approaching the rice paper ceiling. In sumo, only men can go pro.

Professional sumo is only practiced in Japan where rikishi participate in six annual Grand Tournaments. Sumo began as a religious ceremony and the sport remains deeply ritualistic. Tradition forbids women even entering the ring.

Pro sumo only exists in Japan - and only for men

But women have competed at the amateur level since the mid-1990s when Olympic aspirations convinced the sport to go "co-ed". Sumo still hasn't made the Olympics but after 12 World Championships women have become an integral part of landscape.

Unlike many female wrestlers, Tuvshinjargal comes from a country where sumo is incredibly popular. Mongolian rikishi have dominated professional sumo for years; just this month Mongolian superstar Hakuho broke the world record for total career wins.

Wrestling has always been important to Mongolian culture, as one of the legendary Three Manly Sports, and many boys learn sumo alongside traditional wrestling.

According to Naranbat, Mongolians fundamentally changed sumo by bringing in moves from traditional wrestling. While sumo matches can be over in seconds, Mongolian wrestling isn't limited by a ring and requires more time and strategy.

"Before Mongolian wrestlers sumo was only pushing," says Naranbat. "That's why Mongolian wrestlers are high level."

Forging a future

But amateur sumo isn't covered in the Mongolian media, leaving female wrestlers permanently in the dark. People are often surprised to learn they exist.

They're even more surprised to see what these women can do.

"They think that when I'm on this mat I looks like a beast." Tuvshinjargal acknowledges. "But when I step out of this building, I'm just a girl."

And like most people her age she is thinking about the future. After graduating from high school last June, she has been busy applying to universities and considering careers. Most of all, she wants to forge a path as a female wrestler.

"I have given my heart to sumo," she says. "I want to pursue it to the highest level."

It's unclear whether she could make it a career, as amateurs don't usually receive sponsorships. The Mongolian government gives monetary awards to medal winners but with only one major international competition a year even a gold medal isn't enough to live on.

She would love to combine her other passion - acting - with athletics, like her favourite movie star Jackie Chan.

That's not unprecedented - Mongolian sumo champion Ulambayar Byambajav has appeared on several TV programmes. Or she could blaze new territory and become the country's first female sumo coach.

A champion - if allowed to be

Like many of her teammates, Tuvshinjargal can rely on a supportive family. Her grandparents enjoy experiencing sumo through her instead of the TV and their walls are covered in pictures of Tuvshinjargal in her mawashi.

The 2018 World Championship will be Tuvshinjargal's last match in the junior division unless she outperforms the older women to earn a place in the adult division.

It could be long until sumo offers a career for women as it does for men

She already competed on the Mongolian National Women's Team during 2016 World Championships, which placed second overall.

After that, her eyes are on the 2021 World Games and maybe, someday, the Olympics.

Naranbat is quietly confident in his student's ability. After all, she is already strong enough to beat men. Once she masters the strategy, there will be no stopping her.

And if the rules changed, if women were allowed to go pro, would Tuvshinjargal have the ability to make it?

"Yes," he says. "She would be a champion."

- Published25 January 2017

- Published21 September 2016