Panama Papers: Controversy behind ousting of Pakistan PM Nawaz Sharif

- Published

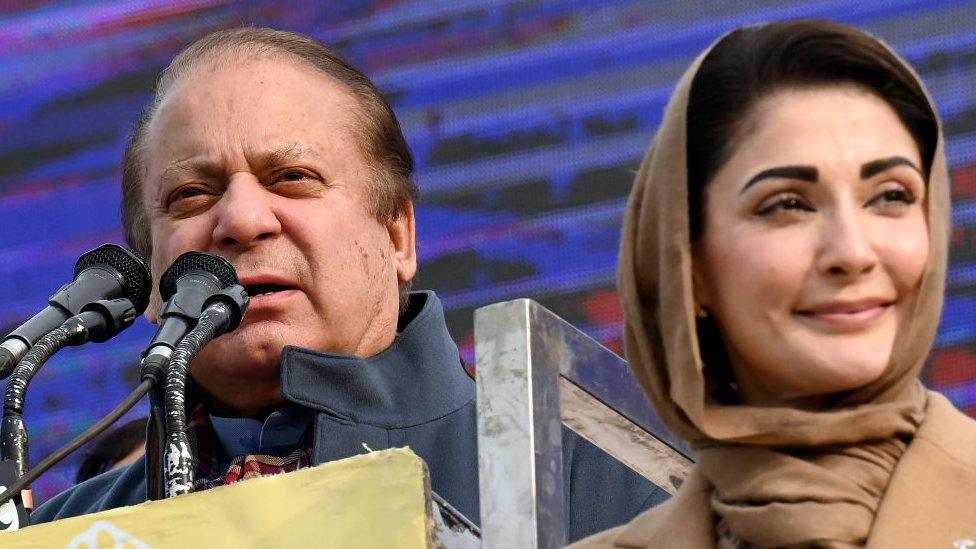

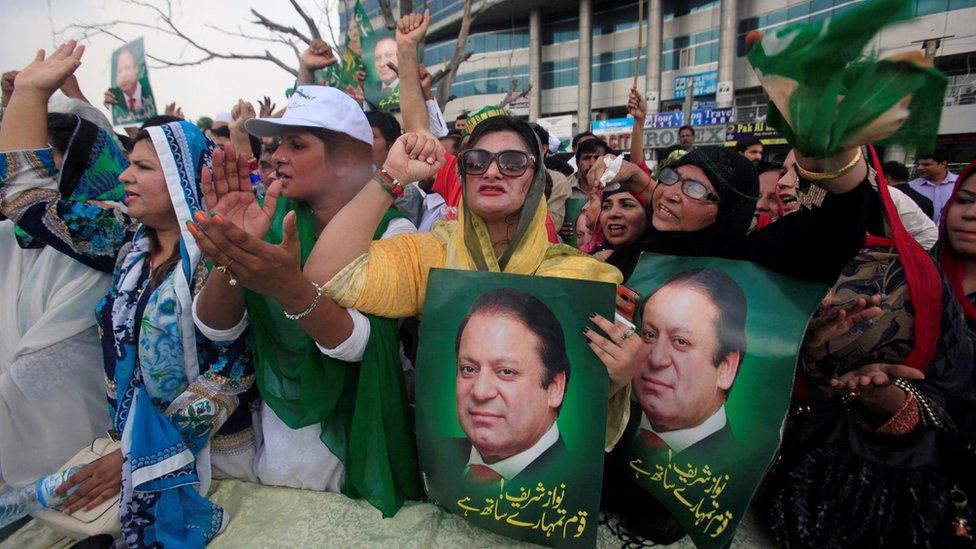

Nawaz Sharif's ousting from office is seen as unjust by his supporters

Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's removal from power may have come as a shock to many Pakistanis, but they are by now quite adept at handling such chaos.

Between 1947, when the country won independence, and Mr Sharif's ousting on Friday, Pakistan has had 18 civilian prime ministers.

All have been forced out prematurely.

This is Mr Sharif's third removal from office, and things do not appear any worse for him now than in 1999 when he was toppled in a military coup.

Back then, he was briefly imprisoned and then sent off into exile to Saudi Arabia.

This time the axe was wielded by the Supreme Court because he failed to declare "his un-withdrawn receivables" from a UAE-based company, Capital FZE, as required under election rules.

Mr Sharif has said his position as chairman of the company was an honorary one, receiving no salary or benefits, and that he agreed to keep the position because it made it easier to obtain a UAE visa as and when it was required.

Many believe, however, that is not reason enough to remove an elected prime minister.

Veteran journalist, Imtiaz Alam, likened it to "the theft of a goat" - a reference to a ruse used by the country's establishment back in 1948 to sack a provincial chief minister.

More significantly, Capital FZE is not linked to the Sharif family's offshore companies or their London property - matters which were at the centre of the Supreme Court's investigations.

The matter of his involvement in those companies and properties, which were originally revealed by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) in its Panama Papers leaks last year, has been sent for a separate trial by a special anti-corruption court.

Earlier, the Supreme Court hearings were marred by controversy on several counts.

It was said that the case belonged in a criminal court, and the Supreme Court, which is an appellate body, initially refused to hear it. But then the court not only admitted the petition for hearing, it also took the unusual step of instituting its own investigation into the case, with a dominant role for the military intelligence services.

Why has this happened to Mr Sharif?

The answer may lie in Pakistan's sustained history of struggle for supremacy between the military and the political class.

Soon after independence in 1947, the government under the watch of the country's founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, sacked two provincial governments - both elected in the 1946 elections in undivided India - thus setting the tone for things to come.

Between 1951 and 1958, the combined military-civil bureaucratic establishment sacked as many as six prime ministers one after the other. The era culminated in the first military coup.

Pakistan's military has been said to protect politicians who agree with its world view

Pakistan's first ever election was held in 1970, and the first ever elected prime minister, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto - who assumed power in 1973 - was ousted in a military coup in 1977 and hanged on a murder charge in 1979.

Since then, the military establishment has alternatively used constitutional manipulation and direct takeovers to keep the civilian leaders in line. In this, it has invariably been supported by the top judiciary.

During this period, the military has developed a huge business and industrial empire which it runs from within, with little or no interference from the state authority.

Many believe this empire can only last as long as the military is able to control some crucial domestic and foreign policy areas, such as relations with India, Afghanistan and the West, or the political narrative and propagation of a particular type of patriotism at home.

For this, they say, the military has often raised and protected politicians who agree with its world view.

But politics has its own dynamics. Once leaders have entered the mainstream, they feel more compelled to increase economic and other opportunities for their voters. This has often forced successive Pakistani leaders to try to normalise relations with India and other neighbours in the region.

From popular leader to coup

Nawaz Sharif started out as the protégé of a military dictator, Gen Zia ul-Haq, back in the late 1970s, and played a major role in the military establishment's various plans to destroy the PPP party of the former prime minister, the late Benazir Bhutto.

That was also the period, according to the Supreme Court-led investigators, when his family wealth multiplied several times over.

The government of the PPP, a left-wing party, was believed in the late 1980s to have opened channels of communication with India and had helped Delhi subjugate a separatist movement in Indian Punjab, which had started during the Zia regime and was believed to have Pakistani support.

But by 1999, having emerged as a popular political leader himself, Mr Sharif followed the same path as Benazir - inviting the then Indian prime minister to Lahore, where they signed the famous Lahore Declaration.

Months later, the Pakistani military started the Kargil war with India, and soon afterwards Mr Sharif was overthrown in a coup.

In the 2013 elections, one of Mr Sharif's main slogans was to improve trade ties with India. Months after winning the election, his government was paralysed by a six-month blockade of the capital Islamabad by the new kid on the block, former cricketer Imran Khan.

Some who sided with Mr Khan during the 2014 blockade of Islamabad have publicly accused his party of receiving instructions from elements in the intelligence service.

Earlier, Mr Khan was accused by a respected social worker, the late Abdus Sattar Edhi, of conspiring with a former chief of the military intelligence agency, the ISI, to overthrow the government of Benazir Bhutto in the mid-1990s.

Edhi, who was approached to join the campaign and says he was threatened when he refused, had to leave the country for some time until the storm blew over.

Since 2013, Mr Sharif is seen to have conceded much policy space to the establishment over Pakistan's relations with India, but his woes have kept multiplying.

And Mr Khan's petition in the Supreme Court over the Panama Papers has finally pulled him down.

- Published28 July 2017

- Published2 February 2024